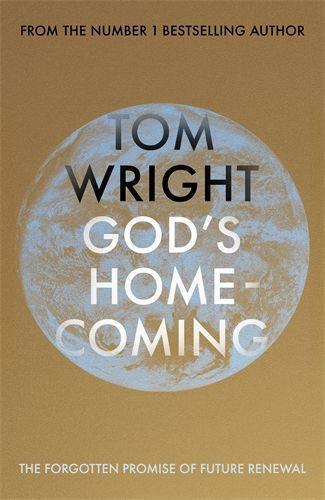

In this sequel to his bestselling work Surprised by Hope, acclaimed theologian Tom Wright corrects common misunderstandings about the end times. It is classic Wright, says our reviewer

In the preface of God’s Homecoming: The Forgotten Promise of Future Renewal (SPCK) Tom Wright says that Christians often make two mistakes when thinking about the second coming of Jesus:

1. Jesus will come back to our world to take us to “heaven.”

2. Jesus will only really become Lord of the world when he finally returns.

In 2007, Tom Wright published his hugely popular book Surprised by Hope (SPCK), the title a homage to C.S. Lewis’ Surprised by Joy (HarperCollins). In that book, Wright challenged the first of these two mistakes. The destiny of the Christian life is not to die and go to “heaven”; on the contrary, God is coming to dwell with us. The correct way to think about Jesus’ second coming, says Wright, is to see it as a “homecoming,” not a “rescue operation.” We’re not fleeing Earth; we’re awaiting a Saviour to come and restore it.

In God’s Homecoming, almost 20 years after the prequel Surprised by Hope, Wright’s aim is to focus on the second mistake: “Jesus will only really become Lord of the world when he finally returns.” There is certainly much overlap in the two books, but God’s Homecoming shifts the centre of gravity from our hope to God’s own homecoming. Where Surprised by Hope was mostly: “what are we waiting for and what do we do in the meantime?”, God’s Homecoming reframes the whole thing as God’s desire to come and dwell with creation.

In line with this, for Wright, there are two kinds of “homecoming”:

1. God filling creation with his glory and knowledge – a cosmic, universal renewal.

2. God personally returning to Zion (Jerusalem) – a relational, covenantal return.

He argues that in the New Testament we see both fulfilled in Jesus. He embodies God’s return to Zion, God coming personally among his people, and the Spirit’s presence in believers and in the Church continues God’s filling of the world with his glory – something that will one day be completed when creation is renewed. The “double homecoming” of God (his return to dwell with creation and his people) will finally be complete when Jesus returns and the Spirit renews all things. Even now, that final renewal is anticipated – experienced in small ways whenever God’s presence brings life, healing, or transformation in the present world.

With this logic, life after death, or as Wright often calls it, “life after life after death,” is not a disembodied heaven but the resurrection into “the new heavens and the new earth” at Christ’s return. Because of this emphasis, Wright tends to treat the intermediate state – the condition of believers between death and resurrection – as a temporary, though blessed, stage on the way to that final destination. He often reminds readers that: “heaven is important, but it’s not the end of the world” – our final home will be embodied life in God’s new creation, not a permanent existence as souls in paradise.

heaven is important, but it’s not the end of the world

If you’re familiar with Surprised by Hope or Wright’s other work, you’ll certainly notice some repetition, such as his critique of Christian Platonism and the insistence that Christian hope equals resurrection and new creation, not “going to heaven when you die.” This familiarity is more prevalent in the earlier chapters, yet as the book progresses, we do see Wright push these ideas on a bit. His focus on the theme of temple, the role of the Spirit, worship, and sacrament as sites where God comes to dwell, are welcome chapters.

Many have challenged Wright’s overarching hermeneutic in recent years, and in light of this, he has provided a whole chapter on “The Apparent Exceptions.” This allows Wright to answer the classic verses people often throw back at him regarding his eschatology. For instance, “In my Father’s house there are many rooms” (John 14:1-4), or “today you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:43). Despite this, some may still quibble with his possible “excessive literalism.” Wright encourages us to avoid the phrase “going to heaven,” on the grounds that heaven will ultimately come to earth. Yet many may still feel that while new creation and resurrection are indeed our ultimate hope, the intermediate state may still constitute more than simply a “waiting room” or a “resting place.” If we’re with Christ, isn’t that paradise? Albeit not the ultimate telos.

In the end, though, even if one pushes back on some of Wright’s exegesis or tone, God’s Homecoming is a timely and necessary reminder. In a church culture still saturated with vague talk of “going to heaven when we die,” Wright stubbornly insists that the Christian hope is bigger, earthier, and more theologically demanding: the God who has already “moved in” by his Spirit will one day make his home here in unveiled fullness.

No comments yet