As thousands take to the streets and Christian imagery is fused with nationalist politics, many are asking whether this represents a legitimate expression of the gospel or a dangerous political theology. The Evangelical Alliance’s Danny Webster explores the issues

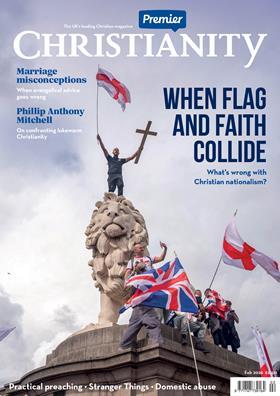

On a September day in central London, crosses were raised amid thronging crowds, the wooden crossbeam daubed with the name of Jesus. This ‘Unite the Kingdom’ march was led by Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, more commonly known as Tommy Robinson – an activist formed in the swells of football hooliganism but now flanked by Pentecostal pastors and leaders from independent churches and breakaway Anglican factions. The streets were covered in St George’s flags as tracts proclaiming the gospel were mixed with speeches denouncing the presence of Islam in the UK.

By mid-December, the story had moved on. Robinson was organising another gathering in central London, this time a carol concert. And when a carol service is greeted by some as a sign of a new revival and by others as a recruiting ground for the far right, there are undoubtedly questions to be asked.

Are we seeing an uprising of Christian nationalism in the UK? And if we are, is this a problem?

Unite the Kingdom’s carol service ended up as somewhat of an anticlimax – both for those fearing that masses would be recruited to radical causes, and for any expecting the hundreds of thousands who had attended previous rallies to come back and find Jesus. The Christmas event attracted between 1,000-1,500 people, compared to the police’s estimate of 150,000 people who joined Robinson’s march in September (organisers disputed this and claimed 3 million attended Unite the Kingdom).

Robinson, who reportedly converted to Christianity while in prison last year, has started talking a lot more about faith – he often links it to his wider political campaigns against immigration and Islam in British society. Meanwhile, Nick Griffin, former leader of the far-right British National Party has founded a new political group called the Christian Nationalist Party. And, in the actions of those such as Nick Tenconi, who describes himself as a “Defender of masculinity, Christianity, and conservative values” the UK Independence Party (UKIP) has moved further to the right. Their 2025 Living Manifesto includes plans to “close the borders; deport those who do not deserve to be here; offer a referendum on the death penalty; declare war on radical Islam and place Christianity back into the heart of government.” It seems that it is becoming beneficial for political figures, especially on the far right, to use Christianity as part of their campaign messaging.

What is Christian nationalism?

Depending on where you stand, Christian nationalism is either the proper outworking of the Christian faith in public life, or a significant threat to democracy and authentic representation of the gospel. A lot depends on how you define it.

The Evangelical Alliance surveyed nearly 900 UK evangelicals in November 2025 and almost all (94 per cent) agreed that Christians have a God-given responsibility to influence all areas of society. More than three-quarters (77 per cent) agreed that Christianity has deeply shaped the UK’s political culture, while 61 per cent said that “the UK is a Christian country and this should be reflected in its laws”. The statement that attracted the lowest support was “Christianity should have a preferential position in politics, policymaking and wider society compared to other religious groups”, with only one in five strongly agreeing. But does support for all – or any – of these ideas make someone a Christian nationalist?

‘Christian nationalist’ is a term most people reject, so no definition will be perfect. The following is intended to be a starting point for understanding an increasingly discussed idea in UK culture and politics. My concise working definition of Christian Nationalism is: “A distinct political theology that requires Christianity to have a preferential position in public life and promotes an ethno-cultural view of nationhood.”

1. Christian nationalism depends on a Christian origin story of a nation. The call for a nation to return to its Christian roots requires a story to be told of how Christianity is integral to the nation.

2. Chrisitan nationalism requires Christianity to have an ongoing preferential position in society, culture and the formation of laws and institutions of a nation. The logic is that, if Christianity is right, why wouldn’t we take steps to ensure it plays a central role?

3. Christian nationalism outworks a particular ethno-cultural view of nationhood as God ordained. This is the idea that a particular group of people, based on their ethnicity and shared cultural history, hold the rightful claim to a particular geographical space – ie: “England belongs to the English”. This view leans very heavily on Acts 17:26: “From one man he made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands.”

4. Christian nationalism has a low view of the value of democracy in society. While political processes and democratic norms are usually supported, they are also often disdained as failing to adequately deal with people’s concerns.

Much of what we see in the UK doesn’t meet all four of these criteria, at least not strongly, but in the words and actions of UKIP’s Nick Tenconi, there is a strong combination of these traits: leaning heavily on Christian rhetoric, wanting to restrict the rights of other religious groups, deporting those legally settled in the UK, and focusing on marches and protests over political campaigning.

Defending Christian heritage

One common feature across Christian nationalists of all forms is a sense that the UK’s Christian heritage has been lost. Christianity and British identity were, they claim, once fused together. Political action is now needed to bring them back together.

This relates to talk of the UK being a Christian nation, or wanting to return to Christian values, but also encompasses fears around Christ being taken out of Christmas, or Christianity erased from British culture.

Christian influence in society is different to placing Christianity in a preferential position

On one level, a nation cannot ‘be’ Christian: it is individuals who are saved by grace, and we should never baptise institutions. But in the same way that we talk about a Christian family or a Christian school, some people argue that we should aspire to be a Christian nation – not claiming that the nation is saved in the way people are, but instead sufficiently governed by Christian teaching and values to reflect God’s ways and help people grow in them.

For a small organisation – whether that’s a family, charity or school – such things can be challenging but manageable. The problem is, the bigger something becomes the harder it is to ensure that core Christian principles run through it. This can lead to more authoritarian methods being employed to sustain the Christian nature of the institution (or nation). In larger bodies, especially nations with diverse populations and a vast array of activities, I believe it is impossible to enforce a Christian mindset without resorting to undemocratic measures.

For example, most Christians would accept that it is reasonable for a Christian charity to advertise a senior position with a “genuine occupational requirement that the postholder be a Christian”. But would we really want to impose a religious test on leadership in public life? Demanding every prospective MP recites the Nicene Creed seems unreasonable to most – but this is what some forms of Christian nationalism can lead to.

Ensuring the freedom of religion and belief for all in the UK means we must accept people practising their faith – and promoting it – in ways we would disagree with or even disapprove of.

None of this stops us being able to value and appreciate all that Christians have done within a society and hope to do in the future. We should be unashamed to proclaim that it is the truth of the gospel that has created social conditions for flourishing and combatting grave societal ills. But it should caution talk of a ‘Christian nation’.

Why is Christian nationalism a problem?

In the EA research, 64 per cent of the evangelicals surveyed thought that Christian nationalism was a worrying trend.

It’s important to remember that Christian influence in society is different to placing Christianity in a preferential position. The former depends on persuasion and consent, the latter on structural enforcement. Requiring a preferential position for Christianity means that other religious beliefs are limited in their freedom. In the same way, it is one thing to give witness to how Christianity has shaped society and desire that to continue, it is another to restrict the freedom of others to pursue and practise their own beliefs.

We should not reject the distinctives of Christianity, nor a passion for seeing society transformed, but we should live this out through a commitment to a confident pluralism that allows space for other beliefs and worldviews. If we believe that Christianity is good and true, we should have confidence to make the case amid other ideas.

One of the most significant problems with Christian nationalism is that it opens the door to racism. There are variations of Christian nationalism that ostensibly reject racist ideas, but this exposes inconsistencies within the approach to politics and public life. The versions of Christian nationalism that are most visible are built around strong opposition to immigration, and not just on the basis of non-Christian beliefs.

The promotion of a nation as the exclusive home of one particular ethno-cultural group, and the view that this concept of nationhood should be prioritised in government policies, inevitably creates a hierarchy of value based on ethnicity. When a set of ideas leads to the degradation of people because of the colour of their skin or their religious beliefs, we should reject those ideas entirely.

The use of Acts 17:26 (see above) to justify national borders and strict immigration policies fails to consider how borders have changed through the centuries, and the accompanied movement of people. This does not mean there is no place for managed immigration, but it should stop us from claiming biblical authority for specific borders for specific ethno-cultural groups.

If we are talking about a Christian nationalism defined by a restrictive view of who belongs in our nation, we should condemn it. Similarly, if the Christian nationalism we see is resting on authoritarian tendencies and opens the door to racism then we should distance ourselves from it as quickly as possible.

4 kinds of Christian nationalism

The EA’s UK director, Peter Lynas, has talked about four orientations of Christian nationalism, depending on the weight placed on ‘Christian’ or ‘nationalism’.

1. Cultural christian nationalists

(small c, small n)

A nostalgic sense that we have lost something of our Christian heritage which needs reclaiming

2. Confessional Christian nationalists

(big C, small n)

Committed Christians who also pursue nationalist political ideas

3. Classic Christian Nationalists

(Big C, Big N)

A theologically driven view of Christian influence and nationhood

4. Co-opted christian Nationalists

(small c, Big N)

The use of Christianity as a way of promoting strong nationalist agendas

What isn’t Christian nationalism

On the one hand, I believe Christians must reject much of what constitutes ‘Christian nationalism’; on the other hand, we also need to be careful of vague or careless criticisms of the term, as these are potentially very damaging to Christian witness.

Criticism of Christian nationalism should not be criticism of the place of Christianity in public life, or the pursuit of influence towards Christian ideals. Stephen Evans, CEO of the National Secular Society, responded to Robinson’s campaigns by saying: “Western liberal democracy wasn’t built on scripture, but on the willingness to break free from it.” You don’t need to defend Robinson to critique Evans’ claim. What I see from the last few centuries of British history is the way that the Christian faith – and the truth of scripture – has enabled liberty, freedom and democracy to flourish.

Some seemingly want to use their criticism of Christian nationalism as a tool with which to shut out Christian influence on public life. As the EA’s Peter Lynas commented last year in the wake of September’s Unite the Kingdom rally: “The question is not whether Christianity will shape public life – it already does – but how. Will the name of Christ be used to feed grievance and exclusion, or to bear witness to the reconciling power of the gospel?”

Sometimes criticism of Christian nationalism can merge with a criticism of socially conservative views on issues such as marriage, family and promoting life before birth. The quest to challenge Christian nationalism can also become a tool to shut out such views from public debate. Proponents of Christian nationalism may hold socially conservative views in some areas, but it is essential that Christians are not cowered into hiding their own beliefs simply because they are shared by others.

It is also important that Christians aren’t lured into political support simply because campaign leaders echo positions that place them ‘on our side’. Politics and policy are complex. Evangelical Christians support a range of different parties for many different reasons. Some issues, such as abortion, have been woefully neglected by politicians in recent decades, but those offering easy answers should be scrutinised with care.

As long as the gospel is preached…?

One Bible passage that has frequently been quoted in recent months is Philippians 1:15-18. It concludes: “The former preach Christ out of selfish ambition, not sincerely, supposing that they can stir up trouble for me while I am in chains. But what does it matter? The important thing is that in every way, whether from false motives or true, Christ is preached. And because of this I rejoice.”

The argument goes that, as Christians, we should celebrate the preaching of Christ whether it happens at a Tommy Robinson march or a Billy Graham crusade. We should indeed join with Paul in rejoicing for those who hear Christ preached and respond. But that doesn’t mean we should endorse or justify all that may accompany it.

Will the name of Christ be used to feed grievance and exclusion, or to bear witness to the reconciling power of the gospel?

The Christmas carol service organised by Robinson was described as being not about politics, immigration or opposition to Islam, but putting Christ back into Christmas. Yet the emails promoting the event played heavily on misinformation about cancelling Christmas lights, aggressive rhetoric against elected Muslim politicians and a call for donations that stated: “Our goal is to strike a blow against those who seek to erode our Christian heritage, and that is exactly what we intend to do.”

I am reminded of the maxim: “What you win them with, you keep them with.” If evangelism is laced with racist, anti-immigrant sentiment and populist politics, this will present significant discipleship challenges for churches.

The gospel requires that we are all transformed. As we seek to live like Christ, discipleship challenges all of us, including our politics, prejudices and priorities. This is as true for those who commit to Jesus at a rally in central London as it is for those who do so during an Alpha course at our church.

How should Christians respond?

Christians are not to be fearful of the unknown or of political activists, but neither should we naively accept all that comes alongside a cross with the name of Jesus written on it. Our faith is anchored in the good news of Jesus; it is bought through his death and resurrection, and our primary response should be to confidently proclaim this message of salvation to all.

Lives are transformed when hearts are turned to Christ, and society changes when the goodness of the gospel is made known. Our first response to Christian nationalism should be deeper confidence in the gospel and an unswerving commitment to its spread. On one level, it’s important not to overreact to the shifting sands of politics. God is not fazed by those who claim him for their cause, and we should not be shocked that this happens.

We should speak with boldness against authoritarianism and racism wherever these arise. Crosses on a march or prayers on a stage do less than a fig leaf to cover these devices of the devil. Christians have to understand the times that we live in; we must engage with the world around us. Daniel is the key biblical example often cited by those encouraging people towards political engagement. Daniel knew the times; he learned the language and the customs. But he did not bow down to idols. He did not stop praying, despite the cost.

That means we must also be willing to speak up when something undermines Christian witness, when we see people bowing down to idols instead of standing for truth. As we seek to be disciples of Christ and see God’s kingdom come on earth, we must act with integrity as we work to influence public life.

No comments yet