We may be seeing anecdotal evidence of some growing, lively churches, says Dr Conrad Hackett. But that doesn’t mean the data shows an increase in church attendance or people identifying as Christian. As a demographer, he explains why the survey methodology is as important as its findings

It’s my job to assess religion data. And in my expert judgement, the survey evidence for a Christian resurgence among young adults in Britain is weak.

As a demographer of religion at Pew Research Center, I analyse census and survey data from around the world to understand how religious landscapes are changing. Between 2010 and 2020, the United Kingdom saw a 13 percentage point drop in the Christian share of its population (from 62% to 49%). Other countries experiencing such large drops included Australia, Canada and the United States.

In such places, younger generations typically are less religious than their parents’ and grandparents’ generations. This pattern is often how religion declines around the world.

However, reports have appeared in the British media about surveys that find surprisingly high levels of religious commitment among young adults. For example, in 2021, the BBC reported on a Savanta poll that found monthly worship attendance among 18 to 34-year olds was three times the rate among people over 55. This poll was commissioned by the Eternal Wall of Answered Prayer.

Last year, Bible Society described a “The Quiet Revival” in which “Gen Z leads an exciting turnaround in church attendance.” This claim was based on a YouGov survey commissioned by Bible Society in 2024. It found that the share of churchgoing Christians in England and Wales was higher among 18-to-24-year-olds than among adults as a whole.

And, according to a Savanta poll commissioned by Tearfund, most British adults under 45 planned to attend church last Christmas, while a majority of older adults did not.

Standards and surveys

It is important to understand that none of these surveys recruited respondents at random from the general population. Instead, they canvassed members of opt-in panels who signed up to take the surveys. These respondents were recruited through methods such as online advertising, self-enrolment and email lists.

My colleagues at Pew Research Center have previously demonstrated that opt-in surveys may be biased by “bogus respondents” who, instead of answering questions honestly, answer with the minimal effort required to complete surveys quickly and receive monetary rewards. Bogus respondents are often a large share of those who claim to be young adults in opt-in surveys. Therefore, the results for young adults may be especially dubious.

Opt-in polls have generated surprising headlines about young adults - and not just in the religious realm. For example, a recent story in Fortune magazine announced an opt-in survey found that 77% of Gen Z job seekers have brought a parent to an interview.

Random selection

If opt-in polls may lead us astray, what kind of polls should we trust? The gold standard in social science research is surveys that use random samples of the population. In such surveys, you can participate only if the researchers randomly select you. You can’t volunteer (opt in). You have to be chosen randomly on the basis of your telephone number or home address.

Surveys based on random samples show that Christian identity and practice are not increasing among young adults in Britain.

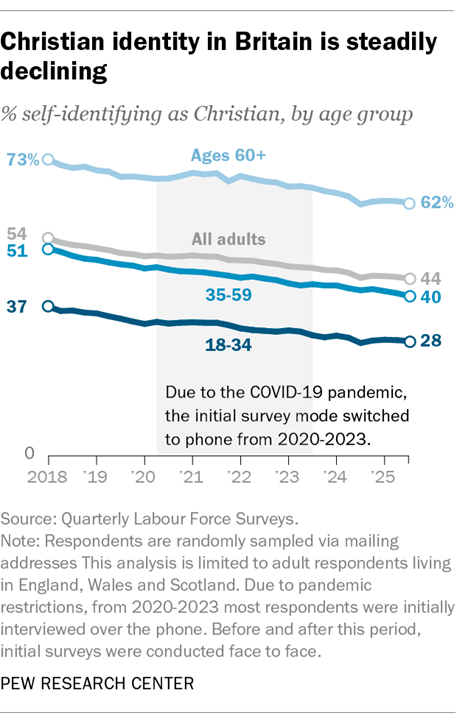

For example, the Labour Force Survey (LFS) measures religious self-identification among more than 50,000 individuals in a typical quarter across more than 20,000 randomly sampled UK households. In summer 2025, the LFS showed that 44% of adults in Britain identified as Christian, down from 54% in early 2018.

Moreover, Christian identification is declining across age groups. In the LFS, 28% of 18-to-34-year-olds identified as Christian in summer 2025, down from 37% in early 2018. Throughout this period, older British adults consistently identified as Christian at higher levels than young adults.

Of course, many self-identified Christians are not regular churchgoers. Since the LFS doesn’t measure worship attendance, we can turn to another long-standing survey that uses random population samples to see how the churchgoing Christian share of the adult population has changed.

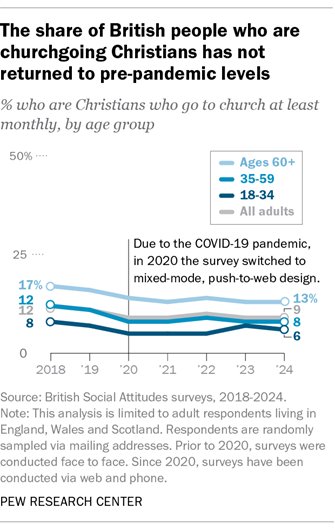

The annual British Social Attitudes (BSA) survey measures religious identity and worship attendance in Britain, based on a random sample of more than 3,000 adults. BSA data shows no clear evidence of a Christian revival. Among all adult respondents, the share who identify as Christians and who go to church at least once a month was 12% in 2018 and 9% in 2024.

Similarly, the share of young adults who are Christian churchgoers has not risen above pre-pandemic levels, according to the BSA survey. Among 18-to-34-year-olds, 6% were in this category in 2024, compared to 8% in 2018.

What about other evidence?

Last week, I went to a Sunday morning service at London’s Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB) church, the largest church in The Church of England. The building was packed by an enthusiastic and demographically diverse crowd long before the service began. I needed to arrive half an hour early to get a seat.

For those familiar with expanding congregations like HTB, it could be easy to assume that such congregations reflect a national trend. However, the Church of England reports that more of its churches “became smaller from 2019 to 2024 than grew.”

Of course, there are many non-Anglican churches in Britain. To understand the full picture of how the British religious landscape continues to change, our strongest evidence comes from sources including the census, the Labour Force Survey and British Social Attitudes survey.

There are pockets of Christian growth in Britain. However, the overall trend seems to be ongoing decline in the share of the population who are churchgoing Christians.

Read Conrad’s original article in full on pewresearch.org