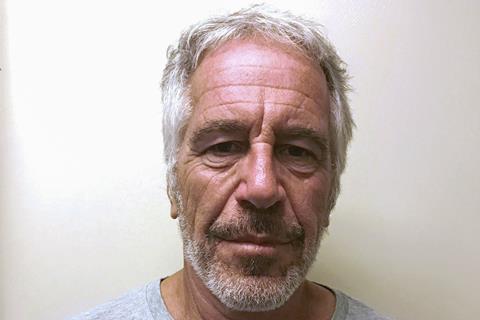

Jeffrey Epstein’s wealth and high-profile contacts put sex trafficking in the spotlight, says Matt Roper. But on National Human Trafficking Awareness Day, the fight against abuse and exploitation - whether on a private island or in a poor Brazilian town - goes on. And it looks scarily familiar wherever it happens

Amid the constant churn of headlines that came to define 2025, one subject kept rising to the surface: human trafficking. Specifically, the sexual exploitation of women and girls forced its way onto front pages like never before.

The revelations about Jeffrey Epstein and his powerful friends were so disturbing that even a world numbed by scandal was forced to stop and take notice. With each shocking disclosure, an often-hidden crime was dragged into the open.

The irony, of course, is that without the famous names, the billionaires, a certain former Royal and the decadent settings, this case might never have been exposed at all - and there would be far less interest in the survivors’ stories. The reality is that for millions of women and girls around the world, abuse and exploitation continue far from the spotlight.

My organisation, Meninadança, has worked for 14 years with young victims of sex trafficking in one of the places where international attention never falls: remote towns along Brazil’s BR-116 highway, a major transport route cutting through some of the country’s poorest regions.

Every day, our teams support girls, most aged between twelve and 15, who are recovering from - or still trapped in - trafficking and sexual exploitation, showing them their true potential, worth and value.

Their experiences are no less brutal than those described in the Epstein files. But they make no headlines - and there’s certainly no public outcry to identify or prosecute the men who abused them.

Same same but different

We began 2025 mourning the death of one of our girls, 15-year-old Duda, who after years of suffering, was murdered by the trafficker she believed she had escaped. Three months earlier, I had met her in one of our Pink Houses - safe spaces where we use dance to reach and protect girls along the highway. She was hopeful, the mother of a baby daughter - fathered by the man who had trafficked her - and eager to tell her story so others might know that change was possible.

For two hours, Duda described how she had been targeted after being forced out of her home at 13, left homeless and desperate. She was tricked into travelling hundreds of miles to São Paulo, where she was locked in a house, raped, beaten and held captive. She had tried to take her own life to escape the pain several times, she said.

Life is a gift from God. But sometimes we feel like giving it back because the burden is too heavy to carry

As I followed the testimony of Epstein’s survivors later that year, those two hours with Duda kept coming back to me. The world’s most famous sex trafficking case was no different to what had happened to this girl - and so many others we work with - in poor Brazilian towns.

Strip away the private jets, mansions and elite connections, and the stories, methods and consequences are the same. Whether on a millionaire’s private island or inside a dirty truck cabin in a remote Brazilian road, the rulebook of human trafficking doesn’t change.

Here’s what Epstein’s crimes can teach us about the scourge of human trafficking around the world today:

1. Child sex traffickers always have more power and wealth than their victims

Epstein was among the world’s richest and most powerful men, mixing with presidents, royals and film stars. But power and wealth are relative. In rural Brazil, traffickers may not afford plane tickets, but they still have money, mobility and connections - while the girls have none.

In one town where we work, the “Epsteins” were construction workers installing mobile phone masts. They had enough cash to buy gifts, clothes or groceries for poor families, using small financial leverage to groom vulnerable girls.

2. They target vulnerability

Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell recruited girls from unstable or disadvantaged backgrounds - those from low-income families, foster care, or who had run away from home. It is exactly the same pattern we see daily.

Duda told us how problems at home meant she ended up homeless, sleeping in derelict buildings at the age of twelve. “Eventually I went to live with a man,” she said. “I thought he wanted to be my boyfriend. But he would beat me up, did whatever he wanted with me, and held me prisoner.”

3. Victims are often dehumanised and blamed

Documents released by the US House Oversight Committee last month included a text exchange discussing the price of girls as if they were merchandise. “1000$ per girl”, the message read, followed by details of their ages, height, measurements and weight.

For decades, Epstein’s strategy was to avoid accountability by blaming, discrediting and smearing his victims. Maxwell referred to victims as “trash”. During a 2006 grand jury investigation, even prosecutors portrayed the girls as liars and prostitutes.

In Brazil, the girls we work with are often labelled “motorway girls” — a term loaded with shame. When one of our girls, 13-year-old Julia, bravely reported to police that she was being sexually exploited by three men in her town, the reaction from the authorities was scepticism. A social worker even described her as a troublemaker and liar in their report. They preferred to believe the sex traffickers - outwardly respectable local business owners - than a poor girl already seen as disposable.

4. Traffickers often use others - frequently women - to recruit

Epstein relied on a network of women, led by Maxwell, to groom and recruit victims. This helped him gain trust while distancing himself from direct exposure. The girls we work with are often lured into exploitation by other women or girls, promising jobs or assuring them nothing bad will happen.

5. Most perpetrators never see justice

In trafficking cases, the imbalance of wealth and power is so extreme that victims rarely see accountability. Epstein’s 2008 plea deal, which spared him prison and federal charges, sent a clear signal that he was untouchable.

Globally, less than one per cent of human trafficking cases end up in court. In Brazil, this is the most frustrating aspect of our work. We have several cases that have been held up for years, due to corruption and indifference to poor, powerless girls like ours.

Recently, one of the girls, aged just twelve, reported being sexually exploited by a local shop owner. When our lawyers received the date for the first official meeting - where police would decide whether the case would even be investigated and the man questioned - it was scheduled for two and a half years later.

6. For victims, the suffering lasts a lifetime

In April 2025, the death of Virginia Giuffre, one of the most prominent survivors of Epstein’s abuse, was a devastating reminder that the harm caused by trafficking and exploitation does not end when the abuse stops.

Years of unresolved trauma and the crushing weight of impunity can leave survivors carrying an unbearable psychological burden. Among the most frequent crises our teams face are self-harm and suicide attempts. When I visited our Pink Houses last year, several girls told me they would not be alive without the support they received.

“It was only then that I began to realise life is precious,” 14-year-old Manu told me. “Because life is a gift from God. But sometimes we feel like giving it back because the burden is too heavy to carry. Here in the Pink House, that burden feels lighter.”

Epstein’s crimes shocked the world. But if we truly want to confront human trafficking, we must look beyond famous names and sensational headlines and listen to the countless people whose suffering remains invisible.

Because, for them, the story doesn’t end when the news cycle moves on.

Human Trafficking Awareness Day will take place on 11 January. Find out more about Meninadança’s work at meninadanca.org

No comments yet