Women are an easy target for Islamic fundamentalists. Both Iran and Afghanistan’s leaders in their different ways have used their own interpretation of Islam to control half their populations, says Jane Hepburn

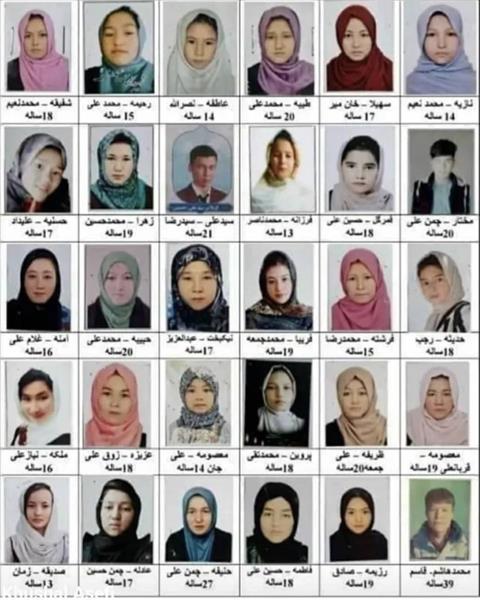

Masoumeh, 14.

Farzaneh, 13.

Sadique, 13.

Amal, 16.

These are just four of the 53 Hazaras, mostly bright young women and girls from the Muslim Shia sect, whose lives were snuffed out by a suicide bomber as they were preparing to take a practice university entrance exam last week in Kabul, Afghanistan. A further 110 were also injured in the blasts. They are alive but broken.

Separated by a curtain, 400 boys and girls from the same school were sat when the bomb went off, but it was the girls who were targeted by a group that believes females should not be educated.

Whatever the rights and wrongs of a foreign presence in Afghanistan over the past 20 years, a generation of girls has been educated. They could jog in the streets and go to the gym after school, they could play football with the boys, they could gather in parks and cafes with their friends, but most of all they could go to school and dream. They could dream of a future where they might become doctors, lawyers, judges and politicians.

The Taliban’s version of Sharia law assumes total control of women, from cradle to grave

But August 15th last year was the day the Taliban marched into Kabul, the final bastion of a country that had surrendered easily. With Kalashnikovs in hand, they rampaged through homes to root out “traitors”, and in their worst excesses forced families to give up their youngest girls as brides for their men. These girls knew everything they longed for had come to an end in that instant. Formal school days were over and a bleak future was staring them in the face

A small private school I have connections with limped along under the radar for a few months until a letter landed on the head teacher’s desk. “Close your school or we kill the girls,” it said. Several equally fundamentalist groups operate, at war with each other in this land. The ultimatum, wherever the threats came from, could not be ignored.

Protests in Iran

Across the border in Iran, protests have been gathering momentum recently over the murder of Mahsa Amini, a 22 year old Iranian Kurdish woman, beaten to death by the so-called “morality police” for “mal-veiling”, the crime of not wearing her hijab correctly. To date 133 have been killed, 40 on Friday alone in Zahedan, near the Pakistan border.

Crimes against women have escalated since the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini declared victory and rolled out compulsory veiling for government employees as his first legislative act in 1979. Fifteen thousand women demonstrated to no avail and 1983 saw the compulsory hijab for all women, with violators subject to acid attacks, beatings, flogging, arrests, fines and job losses.

With no constitution, parliament or president to appeal to, Khomeini’s “Council of the Revolution” let loose a volley of discriminatory laws allowing Muslim men to marry up to four wives, forbidding women to travel without a husband’s permission, removing women from the judiciary, withdrawing guardianship rights to children and imposing the wearing of compulsory veils and gowns to cover the entire body. Prison or worse was the price to pay for disobedience.

An easy target

Women are an easy target for Islamic fundamentalists. Both Iran and Afghanistan’s leaders in their different ways have used their own interpretation of Islam to control half their population. Whereas Iran allows women to work, drive cars and hold seats in Parliament, albeit reluctantly, it ferociously clamps down on other freedoms. In Afghanistan the Taliban’s version of ostensibly the same Sharia law assumes total control of women from cradle to grave. Whereas Iran feigns some pretense at a legal system, Taliban thugs roam the land executing summary justice in the name of Allah and Jihad. Both countries consistently rank in the top ten worst places to be a Christian, with Afghanistan as number one in 2022.

Fundamentalist Islam in Iran may one day hold the world to ransom with a nuclear threat, and Afghanistan’s particular selection of fundamentalist factions, each at war with the other, may well be breeding an Osama Bin Laden mark two. Both nations remain international pariahs, unaccountable and unpredictable.

Whatever the status of each on the world stage, women on the ground continue to bear the brunt of the fundamentalist excesses, liberally mixed with sizeable doses of political posturing and sectarian power play that govern their lives. A largely educated female population in Iran are pushing back, waging war against oppression, either openly or underground, and martyrs to the cause are growing. Men have also risen up to support women, and commentators consider it might only be a matter of time before the government is forced to bow to internationally accepted standards of human rights.

Afghanistan’s women, however, are being subjected to a particularly brutal form of fundamentalism, at the whim of a uniquely erratic band of fundamentalists. Forty years of war have wearied them. Educated, professional men and women have either escaped, or are now unemployed or on the run from the new masters bent on revenge but disunited in pursuit. Seventeen female judges currently, marooned after the exodus last year, are on the run, penniless fugitives in their own land.

Afghan women are at the beginning of another life and death struggle for their freedom, their dignity and their right to live equally with men. Many Christian women have already fled, but many others remain, at great personal risk. The response of the international community to their plight will be the make or break for twenty million of them. Will Christians lead the charge?

No comments yet