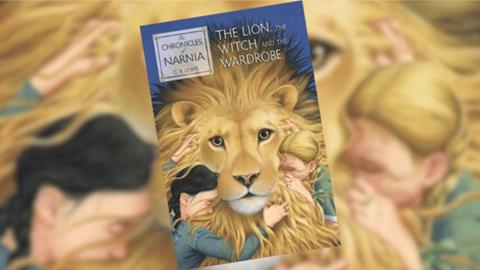

A childhood encounter with The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe changed Michael Coren’s life long before he understood its Christian meaning. On the book’s 75th anniversary, he reflects on the enduring storytelling power of its famous author, C.S. Lewis

In 1965, I was six years old and my life was unfiltered innocence and joy. There wasn’t much money in my family but the love and trust more than made up for that. School was a short walk from home, and at the end of each day our class teacher, Miss Power, would read books to us. Christmas was close and she’d decided on The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe by CS Lewis, one of the greatest Christian writers of modern times.

Of course, I had no idea of that at the time. The teacher’s voice was like stroked velvet and I was captivated by the story of children in a strange, magical land, of battles, talking animals, and even Father Christmas. My family wasn’t Christian, I was too young to grasp the Christian imagery in the book, but I knew I had to find out more.

Mum met me at 4pm, and all I could talk about was this extraordinary book and insisted to my poor mother that I had to have a copy. She never learned to drive, we didn’t own a car, and so she took the bus to the closest bookstore and managed to find a copy. I couldn’t have understood all of the words but stayed up all night looking at them, and the illustrations, and when Christmas came a few days later it seemed different, more alive, more special than ever.

Something was planted in those days, something that would take many years to mature. I became a Christian when I was 24 and I am now an Anglican priest.

Discovering CS Lewis

How much do I owe to CS Lewis, to his writings, and to that book in particular? More than I can ever say. And this year is the 75th anniversary of its publication. It first appeared in 1950, the first written of the seven Narnia novels but not where readers are supposed to begin.

In the following six years Lewis would write an entire mythology based on the characters and places in The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe, beginning with The Magician’s Nephew and concluding with The Last Battle.

Yet it’s the story of four children moved during the second world war to safety in the country, of their discovery of a wardrobe that’s a portal to another land, of meeting Aslan, of talking animals, white witches, prophecies, sacrifice, and yes, the Christian story that rightly dominates the series.

Lewis died on 22 November, 1963, the same day as Aldous Huxley and President Kennedy. At the time, his passing went relatively unnoticed and it was Kennedy’s assassination that dominated the news. Six decades later, however, Huxley is quoted more than read, and John F. Kennedy’s vision of liberal America seems as distant as the Gettysburg address. Lewis is more popular than ever, his books sell all over the world in countless languages, and films are made about his life and, of course, his books.

A legacy alive

There have been attempts to discredit the man that authored the Narnia stories, Miracles, Till We Have Faces, Mere Christianity and countless other books that have changed countless lives, but Lewis is still Lewis and the critics are just the critics. He speaks so clearly, and so convincingly, especially in this cynical age where condescension towards Christianity is considered so fashionable.

The strength ofThe Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is that is works on so many levels and that while it’s a Christian allegory, it’s compellingly subtle and implicit. Unless, of course, we argue that every story of the human condition is in some form a Christian allegory!

Some, of course, would argue that the book is not so subtle. “’Safe?” said Mr. Beaver; “’don’t you hear what Mrs. Beaver tells you? Who said anything about safe? Course he isn’t safe. But he’s good. He’s the King, I tell you.’”

And, “Wrong will be right, when Aslan comes in sight,

At the sound of his roar, sorrows will be no more,

When he bares his teeth, winter meets its death,

And when he shakes his mane, we shall have spring again.”

But to most first readers, it’s an exquisite sense of wonder and mystery that dominate. His friend the late Walter Hooper once told me: “He wrote to communicate, and if ever he forgot that or lost the ability to do so he would simply have given up writing. And it was the Christian message that he was communicating. He received so many letters from people who said they had found faith or answers because of what he’s said or written, and it delighted him. He never became tired of it.”

The films, television adaptations, and stage dramas keep appearing, Lewis himself is arguably more influential than ever, and the Christian world of whatever denomination makes constant reference to Lewis and his work. As it said on a T-shirt I saw earlier this year worn by a heavily tattooed young man, “Aslan Rules?”

No comments yet