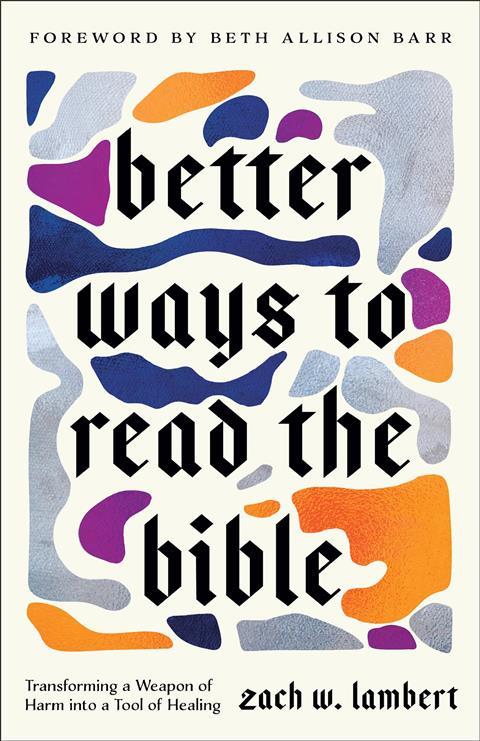

Zach W. Lambert says the Bible has been used to wound as well as to heal. His bold new book offers hope, honesty and a fresh approach for those hurt by the Church, says our reviewer

“I love the Bible, but honestly, there have been times when I kind of hated it,” Zach W. Lambert candidly admits at the start of his new book Better Ways to Read the Bible: Transforming a Weapon of Harm into a Tool of Healing (Baker Publishing Group). His early questions and curiosity about the Christian faith were met not with answers, but exclusion — from both his school and youth group.

The decision by his youth leader to kick him out of the group taught him that “Christian spaces were not safe places to ask pesky questions or voice nagging doubts”

Despite these early rejections, Lambert still eventually found himself graduating from Dallas Theological Seminary and founding and leading Restore Austin, a place that explicitly states: “No matter your age, race, gender, socio-economic status, sexual orientation, disability or background you are welcome here and you are welcome in God’s family”. As a result of this inclusive stance, Lambert has come into contact with many people who have at some time or other, been rejected by the Church at large. “I’ve also talked with numerous folks about the spiritual trauma they’ve endured,” Lambert states; “and in almost every case the primary weapon used against them was the Bible”. His new book is an attempt to counter the ways the Bible has been used to oppress the marginalised.

Perhaps the most damaging lens through which to read the Bible is to believe you have no lens at all. It becomes very easy to say: “The Bible is clear…” and then spout something consistent with one’s moral or political views, while claiming there is no possible other way to read the text. The truth is that everyone who reads the Bible comes to it with their own lens. Anyone who implies they have a ‘pure’ or ‘accurate’ view of the Bible is not to be trusted and should be backed away from slowly.

Lambert counters the weaponisation of scripture by plainly and patiently dismantling some of the most common ways that the Bible has been used to inflict harm. For example, in his chapter on the Literalism lens, Lambert reveals that the doctrine of inerrancy (the belief that the Bible, in its original writings, is completely free from error in everything it affirms) is a comparatively new concept, only codified as late as 1978. The problem with this is that many of those in power have come to reject anyone who does not believe in a literal interpretation of the whole Bible as not real Christians. Lambert points out the danger of making beliefs in six-day creationism a litmus test for true Christianity. Instead, he looks to show that the story of the Bible can still be true even if not every single point is scientifically or historically accurate.

Lambert goes on to show how what he calls ‘Left Behind theology’, the belief that Christians will be raptured before the apocalypse, has not only been around for a mere 120 years, but has led to some Christians viewing the world as disposable – “it’s all gonna burn anyway” etc. This along with the use of ‘Hell-Houses’, haunted house like attractions that attempt to scare vulnerable teenagers into accepting Jesus, have led to very shallow, insecure relationships with God. It’s one step away from evangelism at knife-point, and it has led to lifelong trauma for some people.

All that said, it is perhaps the lens of hierarchy that does the most damage. Any attempt to use the Bible to imply one group of people has dominance over another is not just damaging, but downright destructive. “The hierarchy lens was the lens of the Crusades, the Ku Klux Klan, the Inquisitions, and dozens of other massacres carried out in the name of God and with the justification of the Bible.”

Pointing out all the ways modern Christianity may have got things wrong is not new, but proposing an alternative approach is what many are searching for. His ‘lenses that promote healing’ section includes topics such as Context, Flourishing, Fruitfulness and perhaps unsurprisingly, Jesus. He points out that: “Christianity is not a text-centred faith. It is a Jesus-centred faith”. In other words, the standard for when considering an approach to the world should not be ‘is it biblical?’ but rather, ‘is it Christ-like?’

Eager to reinforce his points, Lambert regularly returns to some of the same anecdotes to reinforce his point, which can, at times, make you wonder if you’ve accidentally already read this passage before, but this is nitpicking. If anything, Lambert spreads his focus so broad, it can make the reader wish that more time was taken over subjects. However, Lambert’s book is so well-researched. He frequently references other books and scholars that give you an indication of where to go for further reading on your chosen topic.

Zach W. Lambert’s book is aimed at those hurt by American evangelical Christianity, and while some of the examples might seem extreme, there are no doubt people all over the world who have suffered from the same weaponisation of scripture. It might ruffle feathers for some, but for those who have been wounded by the Church, this book might be a first step towards the healing love of Jesus.

No comments yet