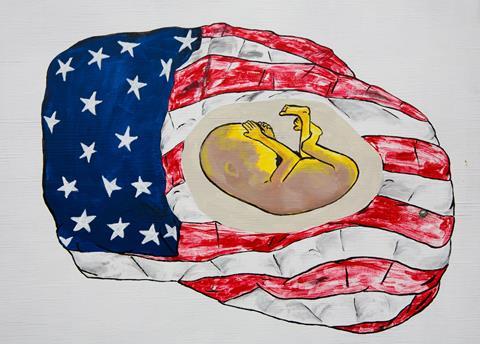

Christians may prefer not to engage in complex and divisive debates about abortion, but there are too many lives at stake not to take a position, says Rev George Pitcher

The leaking of a draft opinion from the US Supreme Court, which suggests overturning the Roe v Wade legal precedent of 1973 that gives American women federal access to legal abortion, is one of those massive moral issues at which we might glance and then want to look away.

Too complex. Too steeped in zealotry from hardliners. Easier to avoid and hope it goes away.

But confront it we must. I’m conscious how emotively pregnant this next phrase is, but there are too many lives at stake to be ruined for us not to take a position.

A central tenet of the pro-choice lobby is, I think, quite straightforward: It’s no part of anyone else’s business to tell a woman what to do with her own body – especially when it’s men in the legislature doing much of the telling (more of which later).

It’s no part of anyone else’s business to tell a woman what to do with her own body

That position is supported by a weight of medical opinion that holds that there is a first period of pregnancy during which cellular structure has the potential to become human, but is not yet so. This is the zygotal stage of pregnancy to embryo – and some would argue beyond. The medical definition of foetal sentience, meanwhile, is unlikely ever to be settled any time soon.

But in purely legal terms, the early stage of pregnancy (time limits will be the subject of constant debate) is at the heart of Roe v Wade’s model of three trimesters of pregnancy, the first of which is not considered relevant to legal intervention, precisely because abortion during it cannot be considered to be taking human life.

That position could be challenged – and it looks like the US Supreme Court intends to do so – but, like it or not, it is a principle on which current abortion policy is decided. Were that not the case, the whole issue of stem-cell harvesting wouldn’t be a live ethical debate if post-conception sentience (as opposed to potential) were proven.

Which brings me to a logical inconsistency that I may hold.

I’m vehemently opposed to assisted suicide, which is also very often promoted as an issue of autonomy over one’s own body. I oppose it for a wide variety of reasons, but for purposes of contrasting it with the calculative issues surrounding abortion, there can be no cases of assisted suicide in which we’re dealing with anything other than a fully developed human being.

But I do see that this differentiation with abortion is tested by another objection to assisted suicide – that it morally compromises the person doing the assisting, particularly medical staff. And that’s to do with the flawed supposition that it’s “my body to do with what I want”. Only if no one else is involved can that be true.

The pro-life position for abortion holds that the someone else involved is the unborn child (or the potential for one). But it could be argued that medical intervention for abortion or assisted suicide is the same moral equation. We can all agree, I presume, that women should never have to take abortion into their own unqualified hands, so it is always going to require the participation of medical professionals. I do see that there can be moral jeopardy in that.

Because of my opposition to assisted suicide, I was approached co-incidentally (to the Supreme Court leak) by Calum Miller, a medical doctor from Oxford University, who teaches Philosophy and has an MA in Biblical Studies. Miller used to share my pro-choice position on abortion but is now firmly pro-life.

There is a danger in paraphrase, but I hope it’s safe to say that Miller holds, as many do, that human life starts at conception and there are greater risks to women’s health – particularly mental health – in abortion than other kinds of support.

As one might expect, Miller is articulate, thoughtful and persuasive. As a doctor, he’s also unafraid to address matters such as pregnancy as a consequence of rape. As I say, he hasn’t won me over, but what I learned is that there is value in the conversation.

His position as a person of faith intrigues me too. Such people (me included in relation to assisted suicide) are accustomed to being told that our opinions don’t matter because we “believe in the sanctity of life”. I don’t know what that catch-all is meant to mean and I don’t suppose the people who say it do either.

As it happens, my objections to assisted suicide and Miller’s to abortion are almost entirely secular. For instance, I believe that a jurisdiction that endorses in law the view that some lives are worth more than others becomes a highly dangerous one. Proponents of voluntary euthanasia concede that no system which adopts it can guarantee that no vulnerable patients will be coerced into it – so how many such deaths are worth it for its supporters to have what they want? The law as it stands is safer.

But it’s undeniably also true that these secular motivations, for Miller and me, may have formed as a consequence of examining such issues through the prism of faith. The Christian gospel is awash not with platitudes about the sanctity of life, but with compassion – not least towards women.

The woman “taken in adultery” (likely to be a euphemism for prostitution; John 7:53-8:11) is liberated from condemnation by Jesus. The woman who has been bleeding uncontrollably for 12 years, thereby irretrievably “unclean” by the standards of her day, has his undivided healing attention (Luke 8:43-48). Mary of Bethany is accorded status with the men when the presumption of others is that she should be serving them (Luke 10:38-42).

There are ways in which we might adopt this model. For sure, we should have more women’s voices in our legislatures. Of the 115 justices that have served in the US Supreme Court, which now presumes to dictate abortion policy, only five have been women. That is a travesty.

This is not to say that women are more likely by virtue of their gender to be pro-choice – but that it’s a scriptural abomination for women’s voices to be excluded. Those voices should be properly engaged - that appears to have been the more than radical example set by the gospels’ women, a few of which I cite above.

That way, we might have a grown-up conversation about abortion law – about what sentience means in relation to embryos; about time-limits that mean you can have an abortion at 23 weeks minus one day but not plus one day; about women’s autonomy over their own bodies.

Otherwise we’re just shouting at each other. And that doesn’t seem to be either the gospel way or a very helpful secular way.

Premier Christianity publishes a wide range of opinions from Christians across the Church. See here for an alternative perspective on this story