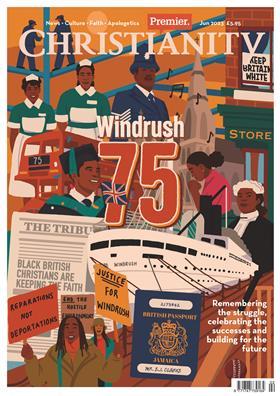

Christian leaders say the government’s decision to pursue a ‘hostile environment’ policy against immigrants has led to ‘triple trauma’ for the Windrush Generation

It’s five years since the Windrush scandal erupted. The revelations shocked the country and have not lost their power to alarm half a decade later. Thousands of people who were invited to emigrate to Britain from Commonwealth countries in the 1940s, 50s and 60s had been treated as illegal immigrants under the Home Office’s ‘hostile environment’ policy. Some were detained, others deported. Many lost jobs or were denied benefits and healthcare they were entitled to.

The chastened government promised to fix its egregious mistakes back in 2018, forcing the resignation of then home secretary Amber Rudd, commissioning an independent review and establishing a compensation scheme for those who had suffered due to Home Office error.

Despite the government initially accepting all the recommendations from the 2020 review into the scandal, this past January the current home secretary, Suella Braverman, announced she had scrapped some critical projects. The government would no longer strengthen the powers of the immigration watchdog, nor set up a new migrants’ commissioner, nor run reconciliation events with Windrush victims and their families.

The compensation scheme has also been torturously slow in getting money to those who have applied. The latest figures reveal only 12.8 per cent of the 11,500 people believed to be eligible have been compensated – and many have received less than the sum they applied for.

Broken promises

“African Caribbeans have gone through what I would describe as triple trauma,” explained Israel Olofinjana, a Baptist pastor, theologian and director of the Evangelical Alliance’s One People Commission. “The Windrush experience in the 1940s to the 60s, the Windrush scandal in 2017, and now the government backtracking on its promises.

He wants to see more white leaders join the campaign for justice: “If we are truly thinking about the body of Christ in Britain, surely we need a polyphonic voice to address this issue together, not just the Black-majority church voices?”

Joe Aldred, a bishop in the Pentecostal Church of God of Prophecy who has regularly worked with the government on post-Windrush issues, said there was a burst of action by churches in 2018 when the story broke, but little since.

Others said it was inaccurate to describe the Church response as lacking. The former Barbados high commissioner to London, Rev Guy Hewitt, is the Church of England’s first racial justice director. He said his own denomination along with many others had been working on both Windrush and wider issues of racial justice since 2018. Indeed, his own appointment was a mark of the progress the Anglican Church has made – before Hewitt there was no senior national figure dedicated to racial justice in the CofE.

Can those who made such catastrophic errors be asked on their own to correct them?

But most were in agreement about the Home Office’s failure to recompense Windrushers caught up in the scandal. Almost all voices active among the Windrush Generation have backed the call of Human Rights Watch for an independent body to take over or monitor how the government is handling the compensation scheme.

“It was not until there was a public furore that you got an appropriate response from the Home Office,” noted Hewitt. “That begs the question: can those who made such catastrophic errors be asked on their own to correct them?” Allowing the same officials to manage the compensation scheme had so far meant the “perpetuation of the injustice, of the inhumanity, the lack of compassion in the system”, he added.

Looking beyond

But Aldred offered a different perspective. Rather than focusing on reforming the Home Office, churches must look at the bigger picture, he argued. In reality, only a tiny fraction of those who migrated from the Caribbean to Britain post-war were affected by the hostile environment. The roughly 12,000 eligible for compensation amount to less than 3 per cent of the total Windrush population in Britain. “It is a huge problem for a small amount of people,” Aldred said, and suggested too much focus was directed at this unrepresentative experience rather than bigger issues around racial integration and harsh immigration policies.

MORE ON WINDRUSH

- Leroy Logan: ‘The Lord commissioned me to join the police’

- Rosemarie Mallett: ‘Jesus calls us to bring about justice. But we can’t do it without him’

- How can you worship the God of the enslavers?

- Nicky Gumbel: ‘If we want to see revival, we must address the sin of racism’

- How Windrush changed the British Church for good

He also recalled outreach work by churches in the 1980s that had helped many Black Britons regularise their citizenship or immigration status, meaning it was relatively rare, in his experience, to find people affected by the scandal within the Black Church community. He also criticised the “Windrush industry” for “stirring the pot”, and said the Church should instead aim its fire at the government’s overall “unchristian” immigration legislation.

Rev Alton Bell, a Pentecostal pastor in north London who also leads the Movement for Justice and Reconciliation charity said he agreed, in part, noting that while it was a horrendous situation, it needed to be put in perspective. He believes the Church should focus on tackling the legacy of slavery and racism through recognition of past sin, repentance and then some form of reparations.

Hewitt said there was now a widespread recognition that the mainstream churches in the UK had failed the Windrush Generation. Now that past sins have finally been recognised, a variety of denominations are united in promising to do better in future. Olofinjana, for example, noted his own Baptist denomination had a whole team dedicated to including Christian Hong Kongers who had arrived recently in large numbers fleeing China’s crackdown. “I think the Church is learning from that Windrush experience, and trying to address it in different ways,” he said.

This article was published in our Windrush 75 special issue of Premier Christianity. Subscribe for half price

No comments yet