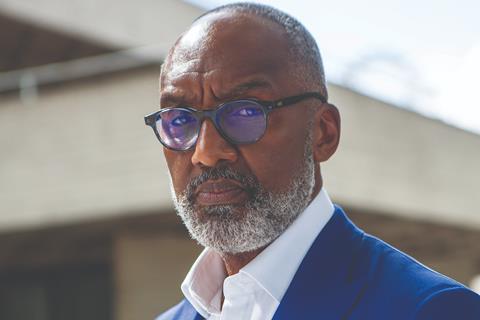

Despite his father being severely beaten by police officers in a racist attack, Leroy Logan persevered with his application to join the Met. His career has seen him valiantly fighting for change – even at significant personal cost. Now a new challenge awaits

When Leroy Logan applied to join the Metropolitan police force in 1983, it was two years after the Scarman report – the first inquiry into relationships between the police and the Black British community. Commissioned after the Brixton disturbances, it heavily criticised the disproportionate use of police powers as part of Operation Swamp, which saw almost 1,000 Black people stopped and searched in just five days, before tensions boiled over in the predominantly African-Caribbean community.

One of Lord Scarman’s recommendations was to recruit more ethnically diverse police officers. And, two years into a career as a research scientist, “the calling of policing” hit Logan unexpectedly. It was not without cost for the then 26-year-old, whose Jamaican father (already deeply suspicious of the police) was brutally assaulted by white police officers just weeks after Logan had submitted his application.

The racist attack, in which Kenneth Logan was “literally beaten black and blue” left him unrecognisable to his son. And it left the younger Logan with an unfathomably difficult decision to make. He had not yet told his family of his decision to join up, and now: “I felt so much hatred,” says Logan, of his feelings towards the officers who had attacked his father. “I just didn’t know how to deal with it.” But, at the same time, he was convinced that his unexpected desire to join the police was of God.

“I’m thinking: Lord, why am I doing this? Science is nice and comfortable,” he says. “And then it came to me: I could make change from within, so no one else gets beaten up like my dad. I suppose it was very idealistic, but I just felt the Lord commissioned me to do this.”

A hostile environment

In a career that spanned more than 30 years, Logan endured the “hostile environment” of a racist police force. “I was ostracised. They wrote the ‘n’ word on my locker. I reported it and nothing was done. And I used to hear about similar things – some people were physically abused – from officers all over the Met.” The experience led to him co-founding the Black Police Officers Association (BPA) in April 1993, the same month that Stephen Lawrence was murdered in a racist attack.

He witnessed genuine improvements in the force, especially in the decade following the Macpherson report that declared the Metropolitan police “institutionally racist”. But speaking today, Logan says he’s “angry” that progress made in recent years seems to have stalled – or even reversed. A lack of independent oversight and a change in emphasis to a “very enforcement-driven” approach to policing means “the look and feel of policing now reminds me of a pre-Macpherson era,” he says, “and I don’t say that lightly.”

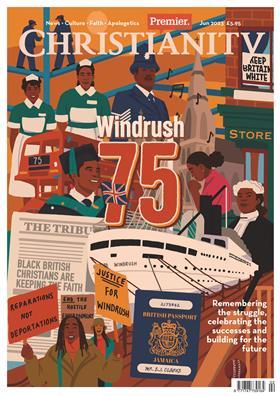

MORE ON WINDRUSH

In March 2021 the rape and murder of Sarah Everard by police officer Wayne Couzens “woke up the public” to problems in the Met that the Black community had long been aware of, he says. When the subsequent Casey review concluded that the force was “a safe haven for predators and people with distorted views: racists, homophobics, misogynists”, Logan says it ‘validated’ the experiences of many non-white ethnic communities.

Pushing for change

Now retired, Logan is a sought-after expert voice, often called upon to share his hard-won insight and experience in the media. Ploughing an often difficult and lonely path has been a heavy cross to bear, he says, but: “If it wasn’t for the Lord keeping me strong, I don’t think it would have happened the way it did.

“I had to go through all of that, you know? You have to go through the crucible of fire to come forth with gold.”

The gold is in being able to keep the conversation going and continuing to push for change, he explains. Through his work in youth mentoring, and in advocating for strong, ethical leadership and clear accountability, he hopes to create a future in which social justice is taken more seriously.

A new calling

At 65, Logan is now re-training to become an Anglican priest. “It’s clear that the Lord’s not done with me yet,” he says.

Then it came to me: I could make change from within, so no one else gets beaten up like my dad

“So many people are downtrodden; they lack hope and aspiration. No one is really talking about mental health and trauma. People are suffering in silence,” he says. “Public servants have a role to play in this, and the Church is key,” he continues. “The love of God should be helping us, as Christians, to be salt and light – and it’s not just nine-to-five or Sundays; it’s 24/7, 365-day stuff.

“I don’t want my grandchildren’s generation to go through the same injustice and inequalities as my children’s generation, my generation, my parents’ generation.

“For me, it’s personal. It is responding to the Lord’s direction. He’s still giving me things to do. As long as I’ve got health and strength, I’ll keep going.”

This article was published in our Windrush 75 special issue of Premier Christianity. Subscribe for half price

No comments yet