As the UK marks the 75th anniversary of Empire Windrush, Mark Sturge unpacks the enormous impact of this generation on the British Church

The story of Windrush is the story of modern British history. It is also the story of British church life over the past 75 years. It is foundational to the growth and development of contemporary African and Asian Christian stories and is the fulcrum to understanding much of modern Christianity in Britain today.

A clash of cultures

After the second world war, a ravished Britain needed to rebuild. The recruitment drive to the colonies – “Your Mother Country Needs You” – established several things. Firstly, that migration was an invitation from the British government; secondly, the parental relationship was broadly accepted by both parties; and finally, the recruitment of skills and expertise were a priority in the rebuilding effort.

This call reactivated Black participation in Britain. Although there had been a Black presence here since the first century, the status of Black people rose and fell over time.

There had already been opportunities for white people of faith to encounter, embrace and extend friendship, particularly when more than 1 million Africans and Caribbeans participated in the world wars, rubbing shoulders with British forces and sacrificing their lives for our collective freedom. But when Caribbean people arrived at Tilbury Docks in 1948, they received a frosty reception.

It soon became evident that the invitation to help rebuild the industries that had lost their workers to war was not accompanied by warm welcomes from local communities and churches.

The migrants knew themselves to be British citizens; a fact they had been taught all their lives growing up in British colonies. However, this status was not fully understood or accepted by those living in Britain, where they were seen as mere economic migrants, foreigners bent on taking jobs away from locals. This came as a surprise to those who had been taught that the ‘Mother Country’ was caring, well-resourced and would provide the opportunity to build a better life.

Most of the passengers on board Empire Windrush (the actual figure varies between 492 to 1,027, depending on the sources) were from Jamaica, then Bermuda, Trinidad, British Guiana, Grenada and British Honduras. Among their ranks were nurses, mechanics, priests, accountants, engineers, dressmakers, plumbers, deckhands, Calypso singers and even boxers.

A primary push factor was economic hardship caused by terrible earthquakes in the Caribbean and Aster yellow disease that made growing crops difficult after the war. A pull factor was that many who had recently fought alongside their fellow Britons in the war were desirous of a return to Blighty.

Britain would later bring in the Commonwealth Immigrants Act (1962) and further reforms in 1968, designed to quell the popular narrative that Black people were stealing ‘white’ jobs. It removed the rights of Commonwealth citizens to live and work in Britain, and limited migration from across the Commonwealth to 8,500 people. This Act, in effect, withdrew British citizenship from those who lived in British colonies. It also meant that the foundations of much of what we see in Black-majority churches today were established within 14 short years.

Christian credentials

While some British parliamentarians were hostile to the idea of Black people settling in this country in significant numbers, others saw Windrush arrivals in a positive light. They surmised that one way to achieve acceptance and integration among the native British was to publicise their Christian credentials. On 8 September 1958, the Daily Mirror highlighted that 60 per cent of Jamaicans were Christians, and churches in the Caribbean were packed.

Indeed, 69 per cent of people in the Caribbean attended a church that belonged to a historic denomination (Anglican, Catholic, Methodist, Presbyterian, Congregational and Baptist). But by 1953, only four per cent of the migrants who had arrived in Britain were attending a British church of the same tradition. The experiences of Rev Carmel Jones MBE and Rev Dr Io Smith MBE – and many others like them – may go some way to explaining why.

Black majority churches are bucking the trend of decline

Before coming to the UK, Carmel Jones had attended an Anglican church in Jamaica, but in 1955 he was told not to return to St Paul’s church in Clapham, London, after he attended a Sunday service. He said afterwards: “I was a boy of 17, when I encountered here one of the first of many acts of racial prejudice that subsequently occurred in my life.”

Smith recounted a similar experience: “The first place I visited was a church, but nobody said: ‘Welcome.’ Everybody stared at me as if I was some strange person from Mars or something. When the church finished, I didn’t get a handshake. Nobody came out to me and said: ‘Come again.’” In fact, she remembered how ministers would hold onto the hands of white parishioners to avoid shaking hers.

MORE ON WINDRUSH

Both Jones and Smith would become pioneering Black-majority church leaders in the UK. Jones founded New Assembly of Churches in 1980 and established the Pentecostal Credit Union (PCU), the largest Black-owned credit union, which offered savings and loans to the Black community who, at that time, were facing substantial barriers from banks and lenders. Without the PCU, many churches we see today would have been unable to purchase their buildings.

Smith led a New Testament Assembly congregation in Leyton, east London, and was an ecumenist, community stalwart and advocate for social and racial justice until her death in 2008. Her work included establishing community clubs and homes for the elderly and homeless young Black people.

Had the treatment of Black Christians such as Jones and Smith been different, their gifts could have been developed for the benefit of the historic Church denominations.

Institutional racism

It was a poignant moment of relief (and not before time) for many minority ethnic Anglicans when, in February 2020, Most Rev Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury, declared that the Church of England was institutionally racist. Addressing the General Synod, Welby lamented: “I am almost beyond words. Personally, I am sorry and ashamed. I’m ashamed of our history and I’m ashamed of our failure. I’m ashamed of our lack of witness to Christ. I’m ashamed of my lack of urgent voice to the Church…It’s shaming as well as shocking.”

This contrition acknowledged that the negative experiences of Black Christians were real, unequivocal and ungodly. It paved the way for an apology to Jones, on 25 October 2020, by Rev Canon Jonathan Boardman of St Paul’s church, Clapham. The 65 years it took for Jones to receive an apology demonstrates the legacy and long tail of racism in the Church.

It is important to remember that this shame is not reserved solely for Anglicans; racism has been a chronic illness in all the historic denominations. The testimonies and accounts of its impact were captured in Richard Reddie’s groundbreaking book, Race for Justice (Monarch, 2022). It speaks to the tension of those Black Christians who stayed in the historic denominations, and those who were signposted to “the church down the road”, which we now call Black-majority churches.

White flight and the Seventh-day Adventists

The Seventh-day Adventists (SDA) denomination was a white-majority church before Windrush. With the arrival of new migrants, it faced the same questions as the historic denominations about how to integrate newcomers. The theological distinctiveness and religious observances made the SDA an obvious home for Black Adventists and, yet, shared faith, belief and practices were insufficient to supplant racial tensions.

The marginalisation faced by Black Adventists in the SDA led them to form the London Laymen’s Forum, which supported the community and advocated for their needs. Growing tensions meant there was a real danger that a separate and distinct Black-majority church conference would form to accompany the North and South of England conferences that already existed to provide leadership. In October 1976, a referendum was held across the denomination to determine whether to have an integrated Church or three separate conferences. Church members voted overwhelmingly – 4,500 to 800 – for an integrated Church.

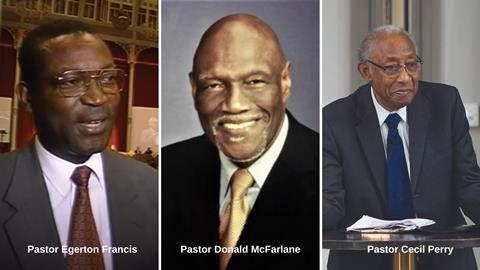

This resulted in a five-point plan known as the Pierson Package which, among other things, called for a Black national director within a year, as well as integrated leadership at all levels of the organisation. Within a short period, the North and South conferences became led by Jamaicans – Pastor Egerton Francis and Pastor Donald McFarlane, respectively. When Pastor Cecil Perry became president of the Union in 1991, the entire leadership of the SDA was Black.

Although this might sound like a success for diversity – and it certainly was compared to the failings of the historic denominations – integration did not eliminate prejudice. In fact, as the make-up of the conference changed, the SDA found that ‘white flight’ flourished – the phenomenon of white congregants leaving a church when its numbers pass a threshold of minority ethnic members. As such, by the 1980s, the SDA had become a Black-majority church.

Black-majority churches

It’s important to point out that racism was not the sole reason for the emergence of Black congregations in the UK. It can be argued that the historic denominations were unable and, at times, unwilling to meet the social, emotional, psychological, financial and spiritual needs of newly arrived Caribbean Christians. But there were also Christians who attended Pentecostal congregations in the Caribbean who wanted to recreate what they had ‘back home’.

This summer, two of the largest denominations to emerge from Windrush will mark their 70th anniversaries – the New Testament Church of God (NTCG), which has 110 congregations and 60 cross-cultural churches, and the Church of God of Prophecy, with 83 congregations. Prior to the establishment of these churches in 1953, there was the Calvary Church of God in Christ (COGIC) founded in 1948 by Mother Mary McLachlan; the Bethel United Church of Jesus Christ (Apostolic), under the leadership of Rev Sidney Dunn in 1955; and the New Testament Assembly (1961) under the leadership of bishops Melvin Powell and Donald Bernard.

What all these denominations have in common are their humble origins in this country. Often, their first services took place in the homes of church leaders, or the member with the largest house. Sundays would see furniture removed from the front room as worshippers squeezed into the space to give praise to God for his goodness. Those who could not find room decamped to the hallway or stairs. When these congregations outgrew homes, halls and community centres were hired, often at great expense to the congregation. The need to provide a more holistic mission resulted in the purchase of their own buildings, and it was here that financial initiatives such as the PCU came to the fore.

The aforementioned COGIC denomination began its life in this way. Mary McLachlan, a 36-year-old dressmaker, travelled on the Empire Windrush with her 14-year-old daughter, Marjory, and her three sons: Edward (19), Godfrey (18) and Aston (8). Soon after she arrived, ‘Mother’ McLachlan started prayer meetings in her home. As they grew, the meetings transitioned to a rented hall in Brixton, south London. The congregation rapidly expanded. In 1952, her husband, Lawrence Oswald McLachlan, who joined the family in the UK later, was inducted as the first minister of COGIC. He then became the national bishop until the family returned to Jamaica in 1963. One of the church’s hallmarks has been the incredible musicians and artists it has produced; theirs was the first Black choir to perform on BBC’s Songs of Praise.

The arrival of the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG) in the UK in the late 1980s changed the landscape of the Black British Church. With a mission to “plant churches within five minutes driving distance” of every household, RCCG has become the most prominent Black-majority denomination, with more than 800 congregations. Most of this growth was overseen by Pastor Agu Irukwu, head of RCCG across the UK, and Pastor Modupe Afolabi, the executive administrator for the past 26 years. RCCG has been joined by various independent churches, including Kingsway International Christian Centre (KICC), which boasts the largest congregation in western Europe. In 2012, KICC purchased a 24-acre site in Kent, debt-free, for £5m.

Building God’s kingdom

It is no exaggeration to say that the presence of Black-majority churches reinvigorated Church life in Britain. Today, they are also bucking the trend of decline that is seen in most traditional denominations. In the early 1970s and 80s, their presence contributed to the emergence of the Charismatic Renewal Movement White Christians who yearned for a move of God – the fervency and embrace of the Holy Spirit with signs and wonders – without becoming part of Black Pentecostalism, found homes in charismatic and house church movements such as Ichthus, the Pioneer network and Newfrontiers. It also provoked growth in white-majority Pentecostal denominations such as Assemblies of God and the Elim Pentecostal Church, which still struggle with Black representation in their leadership despite an influx of Black Christians over the past 35 years.

Racism was not the sole reason for the emergence of Black congregations in the UK

We have seen the sons and daughters of the Windrush Generation leave a lasting imprint on society and on the UK Church. Rev Dr Joel Edwards CBE became the first Black leader of the Evangelical Alliance in 1997. In 1996, Angela Sarkis CBE was appointed chief executive of the Church Urban Fund and, in 2006, became the first Black female leader of the YMCA. Rev Dr Calvin Samuel became the first Black principal of London School of Theology in 2016 and, in 2022, Bishop Mike Royal became the first Black general secretary of Churches Together in England, to name just a few.

Black Christians are here to stay. The task of building God’s kingdom is a joint enterprise. In the words of a prayer spoken by my friend and mentor, Joel Edwards, whom I visited for the last time on Windrush Day 2021: “Lord, make us one: But not all the same.”

No comments yet