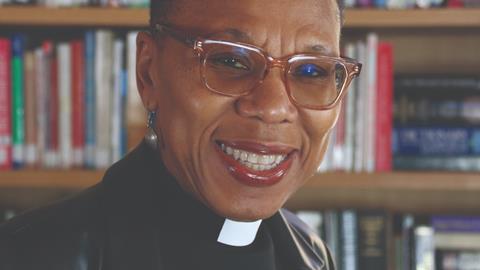

The Bishop of Croydon on slavery, racism and the role of repentance

Rt Rev Dr Rosemarie Mallett, Bishop of Croydon, describes herself as “one of the left-behind children” – minors who stay with family members while their parents seek economic opportunities elsewhere. As a child, she remained in her home country of Barbados – then a British colony – while her mother and brothers travelled to the UK as part of Generation Windrush. They were reunited in 1966, by which time her parents had settled in Coventry.

Rosemarie remembers her childhood in Barbados as content but “extremely poor”. She lived in a chattel house – “a small house that you can literally pack up and put on the back of a cart if you were told in a rush to get off the land”. Her ancestors had been enslaved on sugarcane plantations; her surname a reminder of that brutal history – “we think it was possibly a very small plantation owner who gave that name [Mallett] to a very small plantation”.

Racism wasn’t something Rosemarie experienced until she arrived in the UK aged seven, where her skin colour suddenly became “a problem”. She remembers the mortification of being turned away from a disco as a teenager, along with her white friend who was unwelcome by association. This experience, along with a growing awareness of the civil rights movement in the US, left her “politicised” and with a lifelong passion for racial justice.

Despite struggling with the Church’s historic involvement in colonialism and chattel slavery, Rosemarie says she was “chosen” by God for ordination and, in 2022, became the first female Bishop of Croydon. She has come to see her role as a vehicle for ushering in the kind of kingdom that Jesus called his followers to build.

This June marks the 75th anniversary of Empire Windrush arriving in the UK. What does it mean for you?

I think of all those people who came over on that boat, not knowing what the world was going to hold for them, but with a sense of hope. They were going to do something amazing – build up ‘the mother country’ – and then come back [to their countries of origin] and build up their own communities and grow their families. So there was this sense of joy and expectation. And then what they found, in so many instances, was knockbacks and rejection and marginalisation, and they had to fight through that with tremendous resilience.

I became so disconnected from any kind of institution that could have been part of my forebears’ journey of pain

This [year] is also the 75th anniversary of the National Health Service, and we cannot think of the NHS without thinking of the amazing ways in which people from the Caribbean, and from other diverse backgrounds, have been part of building up that institution. I look at the transport systems in this country, I look at so much that has benefited because those folk came over…So I look back with pride, but I also recognise – as I look back into slavery – the costliness; the amount of racism that so many faced and the challenges that their children faced when they came here. It wasn’t easy.

We’ve got so much more work to do, to right the wrongs of the [Windrush] scandal; to recognise the contributions of these amazing people and to build a legacy and a platform going forward, where no one else will feel that they are unwelcome, that they are marginalised, that there is any hint of them being told that this place is not their home.

Do you see racial justice in terms of activism – Christians joining groups like Black Lives Matter, for example?

I think we’ve got to work at the theological level – that’s the thinking and the being – we’ve got to understand ourselves better. We’ve really got to deepen our understanding of how scripture has been used to create this binary racism and, at the same time, we’ve got to be out there in the world making a difference – whether it’s joining the protests of Black Lives Matter, or joining in with climate justice protests. Some people will choose to do that – that’s how they live out their understanding of social justice. Some people will work on it academically, because it is the theorising and theologising that enables us to learn and to grow. It can’t all be doing; it has to be both that sense of learning and growing, and then being and doing.

We’ve got to be engaged with bringing about justice, because that’s what Jesus tells us we must do. But at every point in time, we have to turn, as Jesus does; we have to stop, we have to pray and we have to ask our Lord to nourish us, nurture us, be alongside us and guide us, with all wisdom and grace and mercy. We can’t do it unless we put it all together holistically.

If Mark Rowley continues to say that the Metropolitan Police is not institutionally racist, he has given a lie to the experiences of so many

The Archbishop of Canterbury has created a £100m fund to address past wrongs, related to the Church’s historic links to slavery. Do you think that goes far enough in repairing the damage that has been done?

I don’t think it’s gone far enough. But I do think that we’re all on a journey and we don’t know what ‘far enough’ is at this point in time. It is a significant step forward, in terms of recognising the past sin, repenting of the past sin and then putting in place a process to move us from where we are. That will help us do some of that work of repairing.

For me, it’s not just about money. It’s about creating a legacy where those who feel themselves part of the Church of England find space within it for their full reflection as members of the kingdom. How do we ensure we do that? That’s not just about creating a fund, but it’s actually building a real platform and basis for the way in which we engage going forward with all diverse people.

MORE ON WINDRUSH

What we do know is that because of the way in which people were ripped out of Africa, that has had such a knock-on effect for the countries where they came from, and the places where they went to. Racism – this binary of Black and white – was born out of slavery. We have to find a way to deconstruct this racism – this whiteness, this blackness – that we have constructed as positive and negative. We have to find the way back from that. And [my hope is] this small amount of money enables us to now invest out of the pain, to invest forwards, so that those coming [in the next generation] will know that people have built a platform for them to be the best that they can be, as God wants them to be.

There has been a lot of talk in the media about the Met Police and the institutional racism that has been rife there for many years. I know you’ve worked with the police, so what are your thoughts on that organisation?

It’s similar to what I say about the Church: there are good people in both institutions doing good work – white and Black – [but] I firmly believe that there needs to be full repentance at the top. And then we can start to see how that ripples through the institution. So, while [Met commissioner] Mark Rowley has good intentions – and I have met him and I don’t doubt his good intentions – if he continues to say that the Metropolitan Police is not institutionally racist, he has given a lie to the experiences of so many people inside and outside of the institution. You need to recognise racism and repent of it.

I think Baroness Lawrence [mother of Stephen Lawrence] said: “If you don’t name it, you cannot deal with it.” Once they start to name it, they will start to live it. And it will not be immediate, but it will show they can also go from lament to action.

You grew up in church. At what point did faith become your own?

In the Caribbean, we went to church. I remember walking with my cousins and brothers through the cane fields in my white dress, white socks, white shoes and my little, what we call in Barbados, a pocket book – they used to be called that in Elizabethan times – with a handkerchief in it, and feeling very beautiful and proud.

When we came over to Britain, we joined the Church…that was just part of who we were. For me, as I became more and more political, that church space became less and less welcoming. My brothers stopped going quite soon. I was in the Girls’ Brigade, and did all of that, but I wouldn’t say that I got a personal feeling of my own faith until my teenage years. You struggle with your identity [in those years], and in coming to a sense of what the world had in store for me, I leaned very heavily on the Psalms. Whenever I was in distress and unable to see the way forward, I would just walk backwards into Psalm 27: “The Lord is my…salvation” – that would just hold me when I thought things were going wrong, [and everything was] so crazy around me. I would just rest in Psalm 27, and that would give me solace and sustenance, telling me to wait for the Lord, he will be there. That helped me in so many difficult times.

Racism – this binary of Black and white – was born out of slavery

It’s interesting that you rejected religious elements of faith and yet chose ordination as your path in life.

I’m going to just connect to that word “chose”. I was chosen. I was an academic for a very long part of my life. And in fact, when I went to university, I went to one of the most (at that time) radical universities in this country, which was the University of Sussex. There were very few people I knew who went to church on a Sunday, because we spent most of our time campaigning or going on marches. I was very, very political. I really rejected the institution of Church because, as I learned more about the way in which the Church had walked together with colonialism, imperialism, chattel slavery, I became so disconnected from any kind of institution that could have been part of my forebears’ journey of pain. I couldn’t find anything about Church, as an institution, that really enabled me to want to be part of it. But [in terms of] my personal faith, I still felt very connected. So I could do that dichotomous thing of saying: “I follow Jesus; I don’t need a church.”

I lived in Tanzania for a few years as part of my academic journey, and there I met a wonderful Filipina nun. She was working at the university as an academic, but was also an embedded faith worker. The order that she was part of worked with local people to really engender that sense of social justice. And I just stopped and thought: There must be something about the institution and working collaboratively, not just ‘me and my faith’. So I went back to the scriptures, back to Jesus calling his Church into being, and looked at what Church should be like, not what it was like – seeing if I could find a way to play a part in bringing about the Church that Jesus called into being. That is a Church where everybody is loved and [which] reflects the beauty and wonder of the Creator. Where there is a place for everyone, and every part of the body has a role to play and is loved and respected. I got to the point where I said: “You know what, I should be part of doing that, rather than sitting outside and critiquing it.”

To hear the full interview listen to Premier Christian Radio at 8pm on 1 July, or download ‘The Profile’ podcast premierchristianity.com/theprofile

No comments yet