A Parliament without prayer? Be careful what you wish for, says Tim Farron MP. In a Chamber often crammed full of egos, there can be no better antidote than to start your day with prayerful remembrance that God is in control, not you

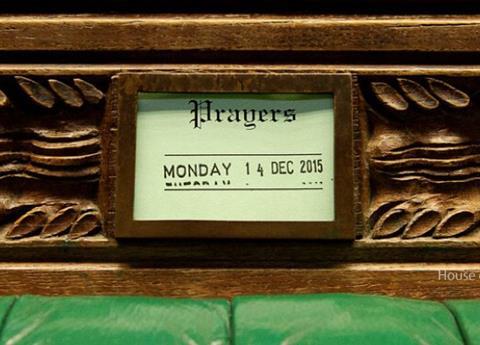

House of Commons Leader Lucy Powell recently spoke of her plans to modernise some of Parliament’s arcane practices. But she confirmed that the tradition of saying prayers in the Commons Chamber to start each day’s session was not up for grabs.

The National Secular Society and Humanists UK were not happy. Both have long campaigned for the abolition of Parliamentary prayers. They believe they are out of touch with society and point to the current Parliament being the least religious in history because 40 per cent of MPs chose to make a secular affirmation rather than swearing on a holy book.

In fact, I myself chose to affirm rather than swear on the Bible following my re-election last year (due in part to my interpretation of Matthew 5:37), so this should not be taken as an accurate measure of MPs’ personal beliefs.

If Parliamentary prayers were abolished, they would only be replaced by something equally partial

I am more sympathetic to their call to end the requirement to attend prayers if MPs wish to reserve a particular seat in the Commons for that day. This means prayers aren’t so much the gathering of the pious as the Parliamentary equivalent of putting your beach towel on the hotel sun lounger before breakfast. Although to be honest, the Commons isn’t usually packed enough to make bagging a seat for the day that important.

So, are Parliamentary prayers an outdated instrument of status on the part of a powerful establishment church? Or a bit of Parliamentary tinsel, a nod to our heritage, an attempt to focus tribal MPs on something higher and transcendent before the gloves come off for the day?

On balance I think we should keep them, although I don’t agree with the establishment of the Church of England or a state-sponsored worldview.

The power of prayer

To state an obvious point, it’s worth saying that I do indeed believe in the power of prayer. Not unusual for a Christian, you might think. In prayer we are crying out to a compassionate, all-powerful God, who reigns and hears us when we call to him. I believe that it’s right to acknowledge him and ask for his help with the work for that day.

The prayers spoken in Parliament are good ones. Usually read by the Speaker’s Chaplain, they call for MPs and all in positions of responsibility to be granted the guidance of the Holy Spirit. They are a call to wise and selfless leadership on behalf of all citizens, reminding MPs that we are not here to represent our own interests or to pursue “love of power, desire to please or unworthy ideals”.

And they are deeply humbling too. A timely reminder that God is the “only ruler of princes” - which helps those of us sitting in the Mother of Parliaments to realise that we really aren’t that big a deal. And asking God for strength and wisdom as we consider weighty decisions is a recognition that we are fallible. What better antidote to a Chamber often crammed full of egos?

A matter of faith

I don’t believe that prayers are an imposition. They are voluntary to attend. Those who don’t wish to participate can and do sit there in respectful silence. If they were abolished, they would only be replaced by something equally partial. Those who are outraged by prayers generally have a deeply held faith of their own. This will often be secular humanism. After all, it’s a matter of faith that there is no god – a conviction that underpins a person’s world view.

Perhaps, consistent with Esther Rantzen’s recent argument during the assisted dying debate, those who hold such a faith in secular humanism should be asked to declare it publicly alongside those of religious belief…

The prayers are a call to selfless leadership, reminding MPs that we are not here to represent our own interests

This is of course in jest, but it’s a reminder that there is no neutral worldview. Replacing prayers with a quiet multifaith ‘reflection’ would simply represent a different kind of exclusive truth claim, as would the institutionalisation of a belief that there is no god.

Deep roots

I believe society has generally moved on from the shallow New Atheist contention that Christianity is dangerous and malign. There is an increasing recognition that the best of Western values are rooted in Christian values, with influential public figures such as historian Tom Holland making the case that we live in a society “still utterly saturated by Christian concepts and assumptions”.

So, if we believe that concepts of justice, equality and the rule of law are all fundamental bedrocks of our society, it is good to remind ourselves that these all have Christian roots. Theologian Os Guinness warns that cutting ourselves off from them leads to a “cut-flower civilisation”, where our values wither and fade because, while we like those values, we reject the source that allows them to flourish.

Parliamentary prayers encourage us to look beyond the flowers to the roots. And for those who want to see, the Christian story is liberating and radical. It tells us that those of us in positions of authority are there not because of our own superior efforts, but because God has put us there. It tells us we are accountable to him and that he expects us to steward his creation with integrity, compassion and justice.

I’d be deeply suspicious of any movement that wanted to erase the very source of what makes us a liberal democracy.

No comments yet