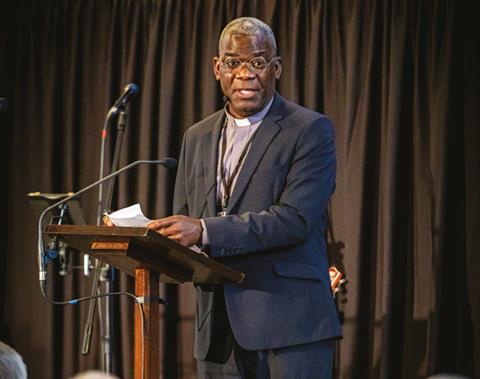

Street Pastors founder Rev Les Isaac OBE hit the headlines last year after his sermon at the parliamentary prayer breakfast prompted a string of cabinet resignations that led to Boris Johnson’s demise. He and his son, musician Jake Isaac, share their thoughts on the illness that put Les’ life at risk just months before, the impact of ministry on family life and the ongoing fight for racial justice

Les

When I left Antigua [as a child] to come to this country, it was very difficult to see what the future held. The trauma of leaving on a Sunday afternoon, having not said goodbye to any of my friends; it was a real shock. Then, when I was seven, my parents got divorced. That was one of the most painful experiences of my life. I thought: I’m not sure if I’m gonna have children, but I do know that I don’t want my family to experience what I experienced.

In those days, parents didn’t speak to children. I couldn’t question my father; I daren’t say a word to him. So in my relationship with Jake, I’d say: “Tell us anything, as long as you’re not rude.” I picked him up from school once and he said: “Dad, I’m 16 now, you know I could have sex if I want to?” I didn’t find it easy, but it was important I let him make his own choices.

As a Black kid, I got called all sorts of names, I experienced physical abuse at school and was rejected by some teachers. At church, I couldn’t figure out why Jesus looked like the people who hated me. And I found it extremely dull and boring! My intention was, when Jake was growing up, that he made his own decision.

I couldn’t figure out why Jesus looked like the people who hated me

It was reassuring when Jake got into music. I knew he was channelling his energy into something creative. Then I began to worry: if he gets successful, are girls going to run after him? Is he going to be upright and righteous? How do I demonstrate that, whether you’re 21 or 60, temptation will always be before you?

I’m not sure where he got his talent from; it’s definitely not from me. I can just about play a triangle. When I went to Twickenham, and Elton John was doing his birthday stuff, Jake came out on stage in front of 40,000 people, and his music was so powerful. He has brought blessing to so many. People recognise that there’s something deep inside his music. I’m so proud of that. He’s doing something I couldn’t do.

When I started Street Pastors, I was on the road a lot. One day, I called the family into the front room and said: “I’m really sorry. I’ve neglected you guys.” At one point, Jake’s mother said she felt like a single mum. I had to work that out. It has been a journey for us as a family. It hasn’t been all hunky dory. We’ve had some tough times. One time, Jake rang me at church and said: “Dad, how come all the other fathers are home with their children, and you’re always at church?” That really touched me. There were tensions, but God helped us through.

When I was hospitalised, it was a very dark time. There were points when it was 50/50. I rang Jake and said “Son, if I go to meet Jesus, look after your mum.” I wasn’t sure whether or not I would leave the hospital. It was a rollercoaster eight months. After that, speaking at the parliamentary prayer breakfast was trivial in comparison. When we talked, Jake said: “You know, it could have been so different. I could have been arranging your funeral.” For us as a family, that whole episode helped us appreciate what God is doing, and wants to do in our lives.

We were very intentional about teaching our children about Caribbean culture, history and racism. As a young Black child, there was no room for ignorance, because these were real things that they would experience. Right from when they were young, I’d say: “Listen, people are not colour-blind. If they tell you they are, run for your life. Because when people see you, they’re looking at your colour, your personality, your character, your skills, where you live – all sorts of things.” We had lots of conversations about it.

This country was very explicit about racism; now it’s not so explicit, but it’s still there. We have moved a long way, but we’ve still got a long way to go. I’m encouraged that there are people – in the Church and outside it – who really want to tackle this, from a biblical and sociological perspective. I’ve always been conscious that it’s the gospel that changes hearts. When we see Jesus and know that he loves us, then we’re able to love our neighbour as ourselves.

Jake

Knowing my dad’s experiences, I’ve always been grateful for the work of Jesus in his life. As a young guy, it’s sometimes hard to be grateful, but being a father now myself, I realise how blessed I am to have a dad who loves Jesus.

When Mum and Dad were heading up a church plant in Crystal Palace, I was 16 and the next oldest person was in their mid-20s. I remember Dad saying: “Why don’t you go and try some other churches?” He was willing to let me go, for me to do a life of holiness and run with my peers and be excited about faith, rather than keep me in the name of appearances. That blew me away.

There were times when I wasn’t the easiest to live with. I had these Destiny’s Child posters up in my bedroom as a teenager. Only years later did I find out how distraught my mum was when she started to see these women in bikinis on my wall. I was just like: Why not? I’ll pray, but I want to wake up and see Beyoncé first thing in the morning. Dad said: “He’s on a journey, let him do his thing.” Those things spoke loud to me.

Every family has its issues, but I look at how my dad has fathered me and, honestly, it’s discipleship at its finest. I’m not saying he didn’t sometimes get it wrong, but his willingness to put aside his own experiences in order to build something new with me has been key to me walking with Jesus now.

My father having the humility to apologise to his family; those things cultivate a culture of honour. They become crucial building blocks. I’ve realised there is a way to do ministry that is sustainable. There are ways in which we can make our family our priority. That’s a healthy generational cycle. And the grace of God is in the fact that, even in the mistakes, great foundations have still been laid. It’s a beautiful thing when a son can show grace to his parents; that’s a reflection of the grace I’ve been shown.

After he preached at the parliamentary prayer breakfast, quite a few people contacted me. My first response was: it didn’t surprise me that he preached about integrity and compassion. He’s going to preach like that wherever he goes.

Fair enough, he has an OBE, but who cares about all that stuff?

But the biggest thought in my mind was: You guys don’t realise that just a couple of months ago, we were talking about what to do if Dad goes to be with Jesus. So I was more grateful, and inspired by the Lord’s work in saving my dad’s life to bring about a chain reaction in the government of this country.

Dad went into hospital for a routine procedure that went left. It was quite traumatic. People as far as Australia were praying for him and it just spoke of his influence on all different levels. Having Dad get me and my sister on the phone and say: “OK, this is what I need you to put in place”, it was a lot. But God sustained him.

There’s a saying: influence is more powerful than profile. But Dad had that influence way before the parliamentary prayer breakfast. People are just seeing the highlights. Fair enough, he has an OBE, but who cares about all that stuff? That is completely secondary to the fact that he still tries to do what’s right and to honour God, and he still inspires his family to do the same.

When George Floyd died, my son, Jesse, was three years old. Two nights after it happened, I was about to read him a story, as I normally did, and I realised that one day, I’m gonna have to tell him a different story, about how someone who looks like his dad was murdered by a white guy in a position of authority. I will tell him that story; I shouldn’t have to, but I will, because it’d be dangerous not to tell him. Denying him parts of history is just ignorance.

It is important that my children are aware of what my father’s and my forefathers’ generations have come through. My friends and peers of other races talk about their forefathers’ experience, so let me talk about mine, so that my children can stand and say: “I am the product of people enduring stuff, and I am going to walk with pride because I’m standing on the shoulders of some incredible people.”

It’s important to know where you’ve come from but, most of all, where you’re headed. No matter what’s gone on before, God wants to use us, speak to us and grow relationship with us, to bring even more beauty to the world. It’s important for me, as a father, to share that stuff and bring Christ’s perspective on it.

REV LES ISAAC OBE moved to the UK from Antigua 59 years ago, aged seven. Disillusioned with the Church, he became a Rastafarian before encountering Jesus in a nightclub toilet. He founded Street Pastors in 2003, and is a church leader, preacher and author.

JAKE ISAAC began playing drums aged three. Signed to Sir Elton John’s iconic record label, Rocket Music, the award-winning singer-songwriter has played with artists that include Sting, India Arie, Paloma Faith and Sir Elton himself. His latest album is For When it Hurts

Rev Les Isaac and Jake Isaac were speaking to Emma Fowle

No comments yet