In the wake of Ozzy Osbourne’s death, Josh Hinton reflects on his introduction to heavy metal, his father’s passionate rejection of it, and why Christians shouldn’t fully separate themselves from the culture due to its darker edges — arguing that faith and heavy metal may be more compatible than we think

When I was a kid, ‘heavy metal’ was a dirty phrase in our house.

My dad, a deeply committed Christian, had walked away from his faith during his teenage years. During that period of his life, heavy metal had become not just his soundtrack but the source of his identity. As he battled with the truly grim culture of his Birkenhead school, bands such as AC/DC, Motörhead, and Saxon offered a safe haven and an image of power.

He could hide in the denim-clad culture of metal, co-opting its apparently limitless arrogance and strength – and so erase any hint of sensitivity that might be interpreted as weakness by his classmates.

In short, for my dad, heavy metal became synonymous with cynicism, male bravado, and a truly staggering number of pints. So when Jesus crashed back into his life just before he left for university, he not only stopped listening to metal – he took all his records into the back garden and smashed them to pieces, signifying his repentance and desire for a fresh start.

He’s always been a talented raconteur, my dad, so this was a story my sister and I heard quite often. It held a dark fascination for me. There was something so other about the music he’d rejected, music I’d never heard. Heavy metal, I learned, was powerful, dangerous, and totally incompatible with Christian discipleship.

The Live Aid Incident

Then, one day when I was about 11, my dad was given the Live Aid DVD for his birthday. It quickly entered heavy rotation on our TV. And there, nestled among incomprehensible pop fluff (Spandau Ballet and Sade), I discovered a few glittering nuggets of this fabled heavy metal music.

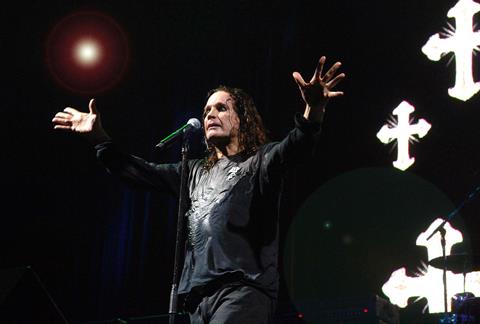

For me, anything with big, loud guitars came under that mythical heading. So, full of wonder and trepidation, I pressed play on Judas Priest, The Who, Status Quo, Queen, and – heaviest of all – Ozzy Osbourne fronting Black Sabbath.

When the songs finished, I cued them right back up and pressed play again. Heavy metal wasn’t allowed but the Live Aid DVD was, and boy, did I exploit that loophole. I watched those bands over and over and over, utterly hooked. I even remember watching them in the church basement on one occasion.

At this point, you might be thinking that the story is about to take a turn for the worse – my father discovering my dalliance with the devil’s music and going ballistic, perhaps.

But in actual fact, at this point, he proceeded to do something much wiser. Rather than angrily snatching the DVD from my fevered hands, he quietly went out to the Virgin Megastore and bought some of his favourite heavy metal albums. Then he came home, sat me down in my bedroom – I can still picture the moment – and handed me the CDs.

He told me to remember they were made by people, not gods, and then, in essence, said I could fill my boots.

For little pre-pubescent me, this was quite a moment. Partly because anything transitioning from Not Allowed to Allowed is pretty exciting for an 11 year-old, but mostly because it represented an amount of trust that made me feel very grown up.

Dad explained that he’d realised making heavy metal into forbidden fruit had given it more power over me, not less. So, rather than fencing me off from this thing that had played a major role in the collapse of his own faith at the age I was just reaching, he decided to trust me with it.

Listen to the music, he was saying, but don’t let it own you like it owned me. That felt pretty heavy, and pretty amazing.

I’ll tell you what else felt pretty heavy and amazing – the music, man! There is nothing in all creation that gives me the fizz quite like an electric guitar at full chat. Twenty years on from that fateful moment, heavy music is still one of my chief joys – and my faith in Christ is still the central fact of who I am. Perhaps the two aren’t so incompatible after all.

Music sacrificed to idols

I tell you all this because a few weeks ago, the chief protagonist of the Live Aid DVD – Ozzy Osbourne, obviously – died.

The huge public outpouring of grief, love, and appreciation that followed and the sheer scale of the Black Sabbath farewell concert days earlier posed some interesting questions for Christians. What do we make of Ozzy Osbourne’s legacy? How do we react to a man who relished and curated his public persona as the Prince of Darkness? As salt and light in a culture that, by all appearances, loves Ozzy and the things he stands for, what does a wise response to the man, the music, and the myth look like?

In one sense, those questions are as old as the church. In his letter to the Corinthians, Paul spends a good amount of space unpacking the ins and outs of how they should engage with the pagan rituals in their city, particularly how and when eating meat sacrificed to idols was advisable (1 Corinthians 8).

Since the year dot, being a Christian has meant living in a complicated world – a world where some things are good, some things are evil, and most things are a baffling mix of the two. That’s what common grace looks like: God’s goodness is so laced through his creation that even when humans are doing stupid, sinful things, it’s hard to get away from it. Meat sacrificed to idols is still good food that sustains the body. Binning it isn’t always the answer; neither is ignoring its origin.

On the one hand, Paul tells the Corinthians to “Eat anything sold in the meat market without raising questions of conscience, for, ‘The earth is the Lord’s, and everything in it’” (1 Corinthians 10:25–26). But a few verses earlier, he writes, “‘I have the right to do anything’, you say – but not everything is beneficial. I have the right to do anything – but not everything is constructive.”

In other words, engaging with the culture around us is rarely black and white. It takes wisdom, and it takes balance. Knowing what’s beneficial and constructive might require some thought.

Which brings us back to Ozzy Osbourne. He’s a cultural juggernaut, both as a singer and a reality TV star, loved by thousands, enjoyed by millions. But there’s an inescapable spiritual darkness to the lyrics and iconography of Black Sabbath and, in a more pantomime-y way, Ozzy’s solo albums.

The band’s name itself, taken from a Boris Karloff horror film, implies the perversion of the Lord’s day – darkness where light should be. The lead song on their debut album (both also called Black Sabbath) tells the tale of a terrified man coming face to face with Satan.

Their fifth album, Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, sports as its cover a painting of a man being ravaged by succubi on a bed adorned with skulls and the number of the beast.

As a result of all this, Black Sabbath remained a bridge too far in my family. While I merrily rocked my way through the metal canon, they stayed out of bounds, and I’ve still never owned a Sabbath album.

But then again, were the evil vibes all just in good fun? One of Ozzy’s signature songs, ‘Mr Crowley’, has a tongue-in-cheek go at the famous English occultist Aleister Crowley: “your lifestyle seemed to me so tragic / you fooled all the people with magic”.

The implication seems to be that all this necromancy business is nothing but bunk. And taking a different view of Sabbath’s schtick, it’s hardly unusual for boisterous young men to say shocking things just to get a rise – or a sale.

Sabbath have said they very deliberately chose the horror aesthetic for their music, reasoning that if people would pay to watch horror films, they’d probably pay to hear horror music.

Putting ‘666’ on your album cover is just as likely to be a sign of mischief or marketing as committed satanism – which, incidentally, is something Black Sabbath have always strenuously denied.

Bassist Geezer Butler has given numerous interviews arguing that Sabbath’s songs are actually more Christian than the opposite, citing his own faith and the lyrics of songs like ‘After Forever’: “Could it be you’re afraid of what your friends might say / If they knew you believe in God above? / They should realise before they criticise / That God is the only way to love.”

Not exactly the sentiment you might expect to find in a lead-heavy Black Sabbath song.

Double listening

Clearly, coming to a clear-cut line on the ‘right’ Christian response to Ozzy Osbourne and Black Sabbath is more complex than it might at first seem. When we’re faced with things like the Sabbath Bloody Sabbath album cover, it may feel right to simply walk away – and for some of us, that may very well be the right place to leave it.

But the Live Aid incident taught me a very important lesson: trying to separate ourselves completely from ‘worldly’ culture is rarely wise. Partly because there’s plenty of God-given beauty in art made by people who aren’t Christians.

Partly because we risk a kind of reverse idolatry when we credit human art with too much power. And partly because, like Paul in Athens (Acts 17:16–34), we do much better when we pay attention to the culture we’re in, affirm what’s good about it, critique what’s not, and connect it wisely to the gospel.

In that chapter, Paul walks around the hub of the Greek world, the birthplace of so much of the culture that dominated the Roman Empire, and sees temple after temple to god after god – including the brilliantly hedged bet of an altar to ‘an unknown god’, on the off chance they’ve unwittingly missed a deity who might get vengeful.

He’s greatly distressed by all this, but when he speaks to the Athenians in the Areopagus, he doesn’t just wag his finger at them. He affirms that they’re “very religious” (v22), before critiquing their scattergun, earthbound approach to worship – “we should not think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone” (v29).

And he unpacks the truth of the gospel in a way that connects to their view of the world, even quoting their own poets to drive his point home (v28). As a result, some of those present become followers of Jesus.

That fruitful approach wouldn’t have been possible if Paul had been completely ignorant of the culture he was responding to. Likewise, when we see our own nation pouring out emotion at the passing of the ‘Prince of Darkness’, our response can only be so effective if it amounts to a blank, a priori rejection of what’s going on.

Instead, we can affirm that the heavy metal Ozzy helped to invent has a joyous oomph and a paradoxically sweet, caring fan base.

We can reject Sabbath’s foolish use of satanic imagery – whatever the rationale, it’s not something to muck about with. And we can tell metalheads that the raw power of rock is a glimpse of God’s glory, and that the cry for justice found in so many metal songs is only truly fulfilled in the redemptive work of Jesus.

No comments yet