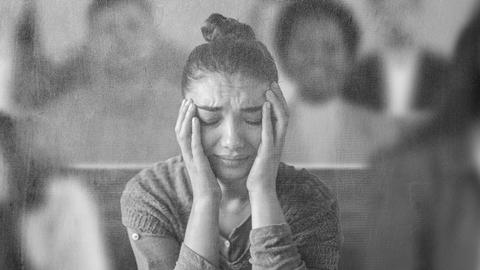

Church should be a refuge – but for many, attending a Sunday service is tough. AJ Gomez investigates why some Christians find gathering together difficult, and what both leaders and individuals can do to help

Life can be hard.

The cost of living stretches your pound thinner than ever. Newsfeeds are rife with division and crisis. Diaries grow with obligations while the hours available to fulfil them remain the same. For Christians, Sunday morning typically offers a much-needed sacred pause – a moment of encounter with God and a chance to reset your priorities.

But that isn’t the case for everyone. For many who are neurodivergent or living with mental health challenges, Sundays can be overwhelming. Going to church isn’t always as straightforward as it appears.

When Sunday feels heavy

Stuart (not his real name) lives with traits of autism and ADHD. “In a typical Sunday service, I can feel shaky, increased heartrate, easily distracted, antsy. No idea why. My body goes into fight or flight.” Even the after-service coffee, where catch-ups and small talk fill the hall, can replicate the anxiety induced by the world outside. “My energy and anxiety levels lead to me and my youngest leaving quickly,” he says.

The noise, sensory overload and strain of socialising are the visible challenges for Stuart. Yet, beneath them exists a deeper struggle, one found in the Church’s posture towards mental health and neurodivergence – in how people with such conditions are perceived, and though often with good intentions, quietly misunderstood.

For Sharon Hastings, that misunderstanding manifested as barriers that were theological as much as they were practical. Hastings is a qualified medical doctor, but a disruptive schizoaffective disorder diagnosis prevents her from practising clinically. She remembers the daunting experience of returning to church after her admission to a mental health inpatient unit. “I worried what people were thinking, whether they would look at me differently, whether I’d ever be treated as a competent, rational adult again,” she says.

My true problem was psychosis, but Christians believed I was possessed

Then there were the harder times, when her wrestle with paranoid psychosis made it near impossible to engage. “One week I might be able to muster a conversation,” she shared, “the next Sunday I could barely say hello, never mind look someone in the eye.” Unable to form connections, she eventually stopped trying, opting instead to refocus on church as a place to commune with God alone.

Schizoaffective disorder affects both thinking and mood, causing episodes of psychosis, delusions and hallucinations. For Hastings, that meant she would experience “mocking pterodactyls”, the belief that she was receiving messages from God via “the network in the fourth dimension” and manic generosity that saw her give “much more money to the church than I could afford”.

Later came the aftermath of a manic episode in which she sent an “ill-judged email” to her entire congregation, the contents of which she would rather not share. “Eventually most relationships were restored,” she says, though it remains a moment that makes her cringe.

Pastoral visits during hospital admissions “made a huge impact”, Hastings says. “They’d come twice a week, read a verse, pray and just sit with me. I might have cried. I rarely had much to say. But they were there, and I valued that.”

Bad theology

When Christian attitudes and theology meet psychology, the Church’s care can heal or harm. “Too often, severe mental illness is misconstrued – especially, though not exclusively, within charismatic church communities – as evidence of demonic activity,” she says.

Prior to her diagnosis, Hastings was attending a prayer ministry at her former church, where she was prayed over to relieve her symptoms. When her condition remained unchanged, she was told that the absence of improvement was evidence of “a demonic stronghold” in her life and that she must examine herself for “a secret sin blocking the effects of prayer”. That notion left her traumatised. “As a young woman whose true problem was psychosis, all I knew was that Christian people believed I was possessed,” she reflects.

Hers is not an isolated incident. Less overt misunderstandings around mental illness can leave Christians feeling anxious, excluded or disqualified from belonging. Stuart, for example, recounts a recent conversation with a Christian friend who told him bluntly: “I don’t believe in ADHD.”

You never get over the death of your child. But the church family moves on

Theologian and former project manager of the Mental Health Friendly Church at Kintsugi Hope, Rachael Newham identifies the problem as “negative lay theology”. Coined by American clinical psychologist Marcia Webb, the term refers to the unspoken beliefs absorbed by Church culture that quietly shape how suffering is perceived.

“It’s the stuff that isn’t really obvious in churches,” Newham explains, “the idea that Christians should be happy – that if you’re full of the joy of the Lord, you’re not going to experience depression.” She traces this back to the way verses such as Philippians 4:6, “Do not be anxious…” can be interpreted as instruction rather than encouragement, turning a pastoral phrase into a moral demand. “You know, it says in the Bible ‘don’t be anxious’, so it’s a sin to have an anxiety disorder…These aren’t things that are necessarily preached, but they’re assumed.” Such interpretations, Newham says, create a painful environment in which someone must face their mental distress and the guilt of feeling it.

When such theology is applied to an individual without an adequate understanding of mental health, the consequences can deepen into spiritual trauma. “If churches practise deliverance ministry,” Hastings says, “they need to be discerning, and involve an experienced Christian mental health professional where there may be mental illness.”

Living in the grey

Research by Kintsugi Hope and Theos has revealed that goodwill is currently outpacing understanding in many Christian communities. “We have this willingness, but not the knowledge. And I think that means those negative lay theologies are perpetuated and have continued,” Newham explains. From that research came the Mental Health Friendly Church training, and a short theology paper intended to address the assumption that faith and feeling always align.

Newham knows that confusion between faithfulness and feeling good, can make Sunday worship a lonely place for those who carry depression or anxiety from causes beyond their control: a chemical imbalance, complex trauma or bereavement. “If the only stories we tell are the stories that end with a cure, then we’re going to have a view of God that doesn’t hold space for the shades of grey within it.”

This can manifest in the way testimonies are shared in Church, she adds. The ubiquitous story of cure and miracle omits the experience of the Christian whose healing looks like endurance. Are churches only willing to recognise the former? Newham, who has lived with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety for 20 years, can attest to a healing that doesn’t necessarily culminate in the removal of a diagnosis. “I think healing is about drawing closer to Jesus,” she says. “A cure is whether or not you are suffering with something at any given time. But you can experience healing without having a cure. And I see that in my own life.”

The perspective that healing is not synonymous with removal of pain was vividly reflected in a story shared by Bryn Abbott, director of development at Mercy UK, a Christian mental health charity. He recalls a couple in his church whose six-week-old baby died suddenly. “Obviously it was traumatic,” Abbott says. “As a church family, we rallied around – cared for them, cooked meals, prayed. It was really holistic support.” But time, he notes, creates a distance. “Fast forward a year, three years, five years – you never get over the death of your child. It’s something they’ve had to continually live with and navigate. But the church family moves on – they’re not staying in that place.” Six years later, the father still finds certain Sundays difficult.

“If he’s had a particularly bad week, and the worship is all really buoyant, and the preaching is about healing or a miracle story – he struggles to sit at the front of church and be so immersed in that. So he sits at the back. It allows him to create a bit of distance between what’s happening and what he’s feeling.”

Unlike Hastings’ experience, this isn’t a matter of ignorance or misunderstanding that can be corrected. Rather, it’s a glimpse into the ache of worshipping while grieving. The reality of lament colliding with an atmosphere of joy.

A safe space

Robert Noble, who is autistic, describes how some ordinary rhythms of church can be difficult to navigate. A healthy guideline, he explains, “is not to come too close”. Instead, “giving the autistic person space, understanding and listening to them. Sometimes we can go on about our own interests – but just give time to listen.”

He pauses before adding that even well-meant enthusiasm can be too much. “Some people are very powerful,” he says. “They talk and ask you questions and it can be a bit overwhelming.” He recalls moments like sharing the peace – a time of hugs and handshakes that, for him, can trigger anxiety. “I just put my hand out to shake, but I’m very nervous then. One lady came to hug me and I jumped back. I thought she was going to fall on her face,” he admits, laughing. “I apologised afterwards.”

Noble demonstrates a need for space that doesn’t nullify the need for connection, just a reconsidered approach to it. Newham, who has experienced panic attacks in church, describes a similar balance. “If someone’s having a panic attack and there’s 20 people crowding around them, it isn’t going to help,” she says. “They might need to step away from the big crowd – but they still need someone to be with them, to say: ‘You’re safe.’”

Healing doesn’t necessarily culminate in the removal of a diagnosis

Noble agrees. These small acts of understanding can be the difference between panic and peace when dealing with the sensitivity neurodivergence and mental illness requires.

Abbott tells me that, on average, someone with complex trauma will only open up about it twice in their life. Mental health and neurodivergence in the Church are fragile territory; the sensitivity and understanding they demand can be complex. And if that statistic is anything to go by, that vulnerability might be a door opened just twice in a lifetime; we may not have many chances to get it right.

But there are simple practices that can contribute to a church culture better positioned to create an environment accommodating of all.

Learn intentionally. If there are people in your church who struggle with mental health or are neurodivergent, seek to understand them and their needs. Noble’s social boundaries are an example of a simple accommodation that can make a world of difference.

Sensitively ask the follow-up question. You may find there is more to a situation than an unexplainable anxiety or depression. As Abbott points out, this could be a practical need - such as a debt that is spiraling out of control - that the church can help address. Either way, understanding (rather than assuming) the root of a person’s problems can help the church respond appropriately.

Signpost. There may be a tendency in your church to keep everything in house but, as Hastings’ case showed, a situation may require a level of professional expertise that isn’t present in your pews. Recommending counselling or referring someone to their GP might, at times, be the wisest and most caring step.

If the Church is to be a space where people can bring their hurting selves, it must know how to accommodate them. When it comes to mental health and neurodivergence, there is still much to be done in understanding and reconsidering attitudes. The stakes are high. Because what a loss it would be if ignorance or misunderstanding were the reason that door opened once and never opened again.

Get the right tools

Here are some resources to help you better understand and accommodate mental health and neurodivergence within your church

I’m Autistic: Get Me Out of Here! - Robert Noble (Kingdom Publishers).

A personal reflection on life and faith through the lens of autism

Wrestling With My Thoughts: A doctor with severe mental illness discovers strength - Dr Sharon Hastings (IVP)

A deeply personal account of living with schizoaffective disorder and holding onto faith

Toward a Theology of Psychological Disorder - Marcia Webb (Cascade Books)

An exploration of how Christians understand psychological disorders today, comparing contemporary attitudes with scripture

And Yet: Finding Joy in Lament - Rachael Newham (SPCK)

Drawing on her own experiences with mental illness, Rachael Newham explores how joy and lament coexist in Christian life, providing practical insights

Training

Mental Health First Aid

Learn how to recognise, understand and respond to signs of mental health and offer the first line of support to those in need

Mercy UK Library

Resources include articles such as ‘Embracing Neurodiversity’, which explores the unique contributions and challenges of neurodiverse individuals in church settings

Mind and Soul Mind Mind and Soul Foundation

Articles and guides on developing robust pastoral care policies, supporting long-term mental health challenges and responding wisely to emotional distress

Neurodiverse Church

Practical guidance for churches looking to embrace neurodiversity, reduce stigma and foster inclusive communities

Mental health friendly church

A one-day course for church leaders exploring how to build understanding, eradicate stigma and create compassionate, mental-health-friendly church environments

No comments yet