He can’t seem to stay out of trouble on social media. But the writer of ‘Reckless love’ might just be one of the most honest Christian songwriters we have

What do Serena Williams, Clint Eastwood, Martin Luther King, Jr and Winston Churchill all have in common? They’re all famous Enneagram type eights. For those not familiar with the personality test beloved of Californians, Christians and psychology junkies, the type eight is also known as ‘The Challenger’. That means they’re not afraid to buck societal rules and, at their best, are resilient, determined and make excellent leaders. At their worst, they can be headstrong and argumentative, fearful of showing vulnerability or not being in control.

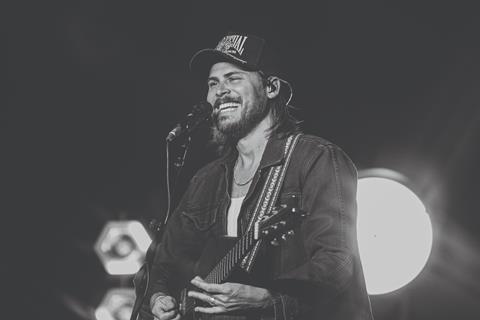

Partway through our first conversation, Cory Asbury tells me that he is an Enneagram eight. We are talking about his social media posts, which unlike the content put out by many figures in the Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) scene are comedic, and often irreverent.

Asbury is perhaps best known for writing the Grammy-nominated worship song ‘Reckless love’. In 2015, he signed to Bethel Music. Further hits such as ‘The Father’s house’ and ‘Egypt’, a collaboration from Bethel’s 2020 Revival’s in the Air album, followed. But five years ago, he moved with his family to Nashville to pursue a change in direction, switching from worship to country music.

Earlier this year, when sexual abuse allegations against Newsboys frontman Michael Tait sparked conversations about a perceived accountability problem within CCM, Asbury caused a stir on social media with a stream of unfiltered comments. In an Instagram story, Asbury said “everyone knew” about Tait’s same-sex attraction. In another, he called the self-promotion of Christian worship artists “antithetical to the gospel” accusing writers of “whoring themselves out” to major Christian music labels, penning worship songs purely for the massive royalty cheques.

This may seem rich coming from a man who admits he made “a lot of money” from ‘Reckless love’ – but fame and finances were never Asbury’s intention, he says. And this distinction is important. He walked away from Bethel because he didn’t like their politics. He walked away from CCM because of his growing unease at profitting from other people’s praise.

‘Reckless love’ drew criticism from Christians who took issue with the idea that God’s love could be described as such, but we don’t go over that old ground in our conversation. Asbury is fine with people disagreeing with his theology he says, but he’s not OK with comments such as: “your family is garbage”. He may have “really thick skin”, but there’s a line. And when radio stations started cancelling him over his comments about Tait, he decided it was time to “step back” from social media entirely.

And yet just weeks later, Asbury was at the centre of controversy again. This time for a parody video which appeared to mock another Christian artist. Forrest Frank had recorded a song from his bed after breaking his back in a skateboarding accident. Frank’s testimony of his miraculous recovery had gone viral online, inspiring a slew of take-offs. Asbury’s “dicey” take was to also write a song from his bed, only the context was his recovery from a vasectomy (the lyrics included, “Snip, snip season but we stay winning souls / Spread the gospel not my seed”). Asbury later explained that finding humour in the darker moments of life is a coping mechanism that stems back to a difficult childhood. But many took offence over the episode – including Frank.

Thankfully the story had a happy ending. Asbury was quick to apologise and Frank was quick to receive it. From the ashes of potential misunderstanding, a genuine friendship emerged (find out more in our follow up interview with Asbury). Unlike much of the discourse that takes place on the internet, here were two Christian men modelling grace, repentance and normal, human relationships – with all their mistakes and imperfections – exceedingly well.

Asbury is not naive, nor unaware that his humour can be polarising. But, like the king’s jester, he says he will continue to poke fun at a pharisaical Church more concerned with appearance than heart – or worship songs that are quick to shame and slow to sit with people in the pain of their lament. For some, he will always be too unguarded to be considered wise. But in a Church world that often values the appearance of perfection over the honesty of real life, I’ll take Asbury’s unfiltered, messy integrity every time.

What was life like for you growing up?

My parents got saved when I was five years old. My mum was always a devout follower of Jesus but, for my dad, it didn’t really take effect until quite recently. He never hit any of us, but he was extremely verbally abusive. It started with my mum, and as I got older, he would shift that rage to me: “You’re a pathetic piece of…” you know, anything that could be said was said. He was an intense man, screaming, yelling, cussing.

When I got into my teen years, I was going wild in the worst ways possible. Drugs and alcohol and girls, but there was also humour that I developed to lighten the load. It was just escapism. If everything’s funny and light, you don’t have to face reality. It’s why people love comedies.

I always loved music though. It was my connection to God. As a teenager, I’d wake up still hungover from the night before, and go to church and sing or play my guitar. My parents found this place in Kansas City and told me it was a music school. When I showed up with my guitar, it was not a music school. It was a Bible school [International House of Prayer Kansas City, or IHOPKC]. I thought: Just kill me now. This is terrible.

We all want the same behind closed doors as on the stage, right? That’s what I fight for daily

I grew up in the Church, so I knew what it was about, but I had never really encountered God. For three months, I absolutely hated it. Then, about halfway into the programme, I was in class, and this dude named Corey Russell was teaching. I wasn’t really paying attention, and all of a sudden, he said: “Holy Spirit, we invite your presence.” In an instant, I’m weeping. People all around me are weeping. I’m like, What the heck is going on? So, I asked God: “Is this you?”

I didn’t hear him audibly, but I felt him – in my heart, or my head or something – and he said two things. The first was: “I’ve seen everything you’ve done.” I was like: Oh, this is not good! The second was: “And I still love you, and I still want you.”

That changed everything for me. After that, I just fell in love with worship, being in the prayer room – even though I hated it before – and that set the trajectory of the rest of my life, really.

For many years you were a worship pastor who also wrote and recorded worship music. But now you’ve moved away from that and are writing country music, is that right?

I’d always been a full-time worship pastor, since I was 19 years old, until five years ago when we moved to Nashville. It’s great not having to wake up at 5am to do sound check. Now when we go to church I show up at 10am and it’s amazing!

My mum prophesied over me when I was a little kid: “You’re a Levite. This is what you’re made to do”, meaning: You’re made to be in the house of God. That’s who you are at your core. But your vocation doesn’t necessarily have to be your calling. That’s the way I think of it. I love the presence of God. Even though I don’t lead worship full-time, I’ve always got my guitar in my hand. I’m always singing and writing and worshipping God in some way.

I really love the country world. They’re the best songwriters I’ve ever been around. Worship music is vastly different from country music. You say the same thing over and over in worship music, because it’s supposed to be accessible. If it’s too complicated, people in church are like: “I can’t sing along to this.” I understand the pragmatism, but there’s something beautiful about just trying to write a great song for the sake of a song.

I wouldn’t necessarily say I don’t do worship music or Christian music anymore, because the truth is I love all of it. But there was a lot of consternation in my heart over the part of the [Christian worship music] industry that seemed really dirty and all about money. I was seeing people’s lifestyles, and I was like: I’m not down with this.

I guess I got lucky with ‘Reckless love’, but it was never about a big stage or money. It was never my intention. And once I saw how – I’m trying to think of an antiseptic, or nice word for it – interesting it was, I was like: Yeah, I don’t want anything to do with this.

Are you saying you left the Christian worship music industry for the secular music industry because you felt that it was purer somehow?

For me, it was a conflict in my soul of making money on worship.

In the temple, the money changers were saying to people: “Hey, God’s not going to accept that sheep or lamb. Come to my place. I’ll switch out the money, and then your worship will be accepted.” They were taking commission off normal people trying to worship God. And Jesus was like: “No, no, no. We’re not doing this! Let people show up with the best they have and let that be OK.” I think that was one of the few things that really p*ssed Jesus off.

I don’t mind a country singer making money off a country show. But there are all these worship entities saying: “Come to my night of worship and pay $120 for front-row seats.” I’m not good with that. That messes with my spirit. It feels like the purity of it has been lost. It feels too much like the money changers at the temple.

And then people come into a songwriting room going: “I know I’m going to make money on this song if it blows up on CCLI” [Christian Copyright Licensing International distributes royalties to songwriters when their songs are sung in churches]. People come in with that intention. They might not say it, but they do. I’m not gonna have anything to do with that.

You recently said that “everyone knew” about Michael Tait. That’s a heartbreaking indictment of the Christian music industry. Can it ever be fixed?

That’s the question I wrestle with every day.

When I said that about Tait, I meant everyone knew he struggled with homosexuality [not that there were allegations of abuse against him]. Everyone was all p*ssed off, like: “Why didn’t you tell the world about Michael Tait?” I’m like: “Bro, I’m not friends with Michael Tait. I’ve never spoken ten words to him. I just know he’s gay.” And so did everyone else.

Glory was not supposed to be ours. Fame, accolades, fortune, they corrupt

The struggle is something I have grace for, just like the worship leader who is struggling with alcoholism. When we’ve given into it and we just say: “Who cares? I’m just going to show up drunk.” Or, in the case of someone like Tait: “I’m just going to do these things that I shouldn’t be doing” – I’m not cool with that. But I don’t have a way to fix that. I didn’t know what was taking place behind closed doors. Maybe some people did, and it sucks that they didn’t say anything. But if it’s not something I’m seeing with my own eyes, I can’t be the whistleblower. I cannot change people. All I can do is hopefully provide an example of what it looks like to walk in integrity. We all want the same behind closed doors as on the stage, right? That’s what I fight for daily, because that’s important.

So honestly, I pray and ask God to purify his temple, and I hope that he does. But he’s been using broken people for a really long time. People think if it’s still making money, it’s got God’s stamp of approval; it’s still ‘anointed’. That’s not the truth. Sometimes he exposes it – and sometimes he doesn’t. I know a lot of folks who are still really popular, who have stuff that has happened in the past that is not great. God might expose it. God might not. It’s not really my call.

Is there a lack of accountability for Christian musicians and worship leaders? With the platform and money involved, is it possible to avoid such things happening?

Yeah, people aren’t made for that. No one’s made to carry that weight. It’s not a thing that we were created to do. Glory was not supposed to be ours.

Fame, accolades, fortune, they corrupt. You know, it’s like the old adage: revival makes money and then money kills revival. You can’t change the way it is. You can only hope that people do things for the right reasons – and know that you’re doing it for the right reasons – and the second that you’re not, be done, or find a way to repent and change.

You also said - on social media - that using social media to promote yourself was antithetical to the gospel. What did you mean by that?

There’s nothing wrong with telling people about your music. But we build a lot of theology out of necessity. We go: “I need to tour 200 days a year to make my lifestyle work and to make money and to take care of my family.” So, I build this theology that it’s good to market myself and constantly video everything that I do. That’s absolute garbage.

You watch the life of Jesus. He would heal someone and typically say: “Don’t tell anyone.” Part of that was self-preservation, because he wasn’t ready to die yet. But the other part was like: “I don’t need to build my ministry.” He didn’t pass round the collection plate. He didn’t build the Jesus brand.

If you want to tell people about your music, tell people about your music. But don’t do it with the intention of building your kingdom. Do it with the intention of helping someone with that song you wrote, to offer encouragement, or alleviate anxiety or depression, or just provide a general sense of levity or joy. That’s not what I see in our culture nowadays. It’s about marketing yourself, not humbly offering your song to the world. I’m just so turned off by that. And I do truly believe that marketing yourself is antithetical to the Bible.

I am making a slight distinction between marketing your music and yourself. And some people are going to go: “That’s not a real distinction.” Great. Have fun with that argument. I couldn’t care less. I’m saying: Do things for the right reasons. Stop putting yourself on a pedestal. [The Bible says] don’t “let your left hand know what your right hand is doing” [Matthew 6:3]. We love videoing ourselves giving to the poor and saying: “Look what I just did!” Don’t freaking tell people. Just live your life and be OK with your reward being in heaven, because Jesus would say: “Good. You’ve got your reward. Enjoy people liking that for about five minutes.”

So we’ll never see any social media videos of Cory Asbury on a mission trip anywhere?

No, no. I really can’t stand that stuff. I understand that it’s helpful to some people. But my conviction is that I’m not going to do it.

Is that one of the reasons you keep your social media quite lighthearted?

Yeah, I think levity is important in this day and age. Comedy is important because it has a licence to poke fun at things that are taking place in culture. Think of the king’s jester. He even makes fun of the king [in a way] that no one else could. It’s such a succinct way of pointing out a flaw and asking: Should we be doing it this way? Rather than writing an essay that no one’s going to read or doing a four-hour podcast, I can make fun of something in 15 seconds, and you know exactly what I mean.

Like your recent video poking fun at Christian songs that suggest God will just miraculously ‘zap’ anxiety with a thunderbolt?

So, here’s the thing: I could have written a super sombre song about it, or an essay that took people an hour to read. Or I could just write a stupid little satire song, and everyone goes: “That’s so funny that the Church believes you can just go: ‘Bibbidi, bobbidi boo’ and all your anxiety is gone in the name of Jesus!”

Sometimes it works like that, but for the vast majority of folks, it doesn’t. We shame people for having depression and anxiety in Church culture and say: “You can’t take medication; you better plead the blood of Jesus. And if it doesn’t work, just deal with it for the rest of your life.” I’m like: “Y’all are silly, and you need to know that.” The best way to say it, in the shortest amount of time, is to write a stupid song about it.

I’m guessing you get a fair amount of pushback from people…

I mean, I’m an eight on the Enneagram, so I love tearing things down and reforming. Some people are naturally like that, but for some people, there are things that took place in their life that caused them to be that way. I don’t think I would naturally be as intense as I am if not for my childhood experiences. When I’m running up against an attitude that’s super strong, I have to rise above that with even more strength and intensity.

This Forrest thing brought up a lot of really good stuff in my heart, because I knew that I would have to humble myself and apologise. I would essentially have to lose. And when I was young, I would not lose, no matter what. It was a reflection of my dad, when I was 13 years old, yelling: “You’re pathetic” when I couldn’t chop wood. I had to get so much healing from that and learn that it’s OK to lose. It does not define me. We are sons of God. That defines who we are.

Comedy is important because it has a licence to poke fun at things that are taking place in culture

I’m fine with people saying: “God’s love isn’t reckless”; “That video was stupid”; “I disagree with your take on anxiety”, but what’s happened recently is: “You are a heretic”; “You are evil”; “Your family is garbage.” I’m like: Wait a sec. This is a whole different level of disparaging. This is character assassination.

It has taken its toll. When it becomes: “He’s sent to lead people astray”; “He comes from IHOPKC, which is evil”; “Bethel is evil”; “They’re all false ministries dealing with false gods”, I’m like: OK, y’all are actually clinically insane. It’s wild.

I am pretty unashamedly myself [on social media], but when it becomes so misunderstood, that’s a different level. People would rather me just post some cheesy scripture taken out of context or be the perfect veneer of a human being. It’s not me. I’m not a company man. I never will be. Say what you want, but when it becomes: “Corey is evil” I’m like: “Guys, come on. I’m fighting for truth and integrity and vulnerability and honesty here, and I’m getting raked over the coals for my take on Michael Tait because I said everyone knew? Everyone knew! Why are you saying I’m complicit? This is the worst take I’ve ever seen.”

Does it ever get to you?

Absolutely. It got to the point where I didn’t want to open my phone. Even if I wasn’t looking at social media, people were sending me comments or articles. Everyone just cares about headlines and clicks. They don’t care about human beings. I just couldn’t handle it anymore.

I’m weighing everything right now. It’s too steep a price to pay to have people misunderstand satire and have radio stations say: “We’re taking Corey’s music off air.” It’s not worth it. I’m not meant to disciple the world via social media. All I can do is affect the people that are around me. The rest is up to God.

To hear the full interview listen to ‘The Profile’ podcast.

You can also read more from Cory in our follow-up interview at premierchristianity.com/asburyfrank

Since speaking to Premier Christianity, Cory has released a video announcing his return to worship music:

1 Reader's comment