The Pulitzer Prize-winning author says she’s proof that the world isn’t as antagonistic towards Christians as many assume

It’s the classic icebreaker question: If you could invite anyone to dinner, who would you choose?

It’s fun to daydream. But if you’re president of the United States, the question doesn’t need to remain theoretical. When Barak Obama had the power to invite anyone he wished to the White House, he chose Marilynne Robinson.

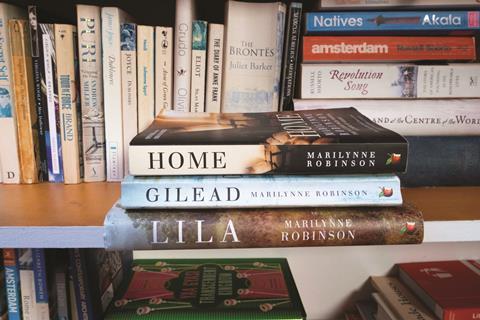

The critically acclaimed novelist is best known for Gilead (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), a fictional autobiography of an elderly pastor that won the Pulitzer Prize in 2005. There are many other remarkable things about the 80-year-old. Her novels have been translated into 36 languages, she has honorary degrees from countless universities including Oxford and, despite incredible success, she neither knows nor cares how many books she has sold. Yet when The Guardian wrote about her, they were surprised to find she is both “a very good writer” and “a very serious Christian”. Maybe they’ve never heard of CS Lewis, Flannery O’Connor or Evelyn Waugh?

Speaking from her home in upstate New York, the self-describing Calvinist tells me her career is proof that writing overtly Christian books does not preclude mainstream success. The world is not as antagonistic towards us as we sometimes believe. She has been allowed to “write about what I’m interested in” and is grateful for the “generosity” of her readers.

I can’t be in the position of judging the intentions of God. That’s above my paygrade

Robinson takes “great pleasure” in exploring theological themes. And this month sees the release of her most theological work to date. Reading Genesis (Virago) is a work of non-fiction which has been praised by Dr Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury, as “a work of exceptional wisdom and imagination” and promises a fresh approach to the first book of the Bible.

Why did you write Reading Genesis?

It’s an odd thing to be offering what looks like a novel interpretation of a book that’s been interpreted for thousands of years [laughs]. But it seems to me that is what needs to be done…I think the reading of the text has been impoverished by the scholarly traditions that surround it. Conventional interpretations of Genesis minimise the text and are rather disparaging of the Old Testament God. The documentary hypothesis, which is an assertion that the text is not intrinsically meaningful, is a terrible beginning for any serious attempt to give anything its due.

How do you expect readers will think differently about Genesis as a result of reading your book?

I hope that I’ve complicated the way in which in which it’s read, and enriched it.

A lot of my books are really myself wondering about something. This book is basically following through questions or observations that I have read or taught many times, never to my own satisfaction.

How concerned are you with the debates over whether there was a literal first Adam and Eve?

We don’t know, and we won’t know. We know that the figures of Adam and Eve are used to assert the likeness of human beings to God, and that’s the important thing to conclude.

I can’t imagine what literalism would even mean in the context of the dewy morning of the first creation. Questions like that obscure the real substance of what has been discussed. I find there’s too little interest in the conception of human beings as images of God, and what that means.

I’ve noticed that humankind created in the image of God is a theme you often draw on. What does it mean to you?

I’m a Calvinist. I admire his metaphysics. He begins the Institutes of the Christian Religions by talking about the beautiful detail of our existence. He talks about toenails, but also the fact that we can solve problems in our sleep and imagine things that have never existed. The potency of human capacity for creating, perceiving and recreating has a great deal to do with us being made in the image of God.

If we truly believed that every person we meet is made in the image of God, we would treat them with great dignity and respect. Has that been your experience of interacting with other Christians?

That respectful expression of Christianity was typical in my experience, but now it is almost forgotten as a trait of Christian culture. I think that’s terribly serious. People who declare themselves Christian are always accusing other people of being declined and decadent – I think the words probably apply more appropriately to a great many of them.

Are you thinking of any groups in particular when you say that?

Our gun lobby, for example. We have lots of people that go around waving crosses and standing in the way of what is civilised, humane and, as ever I understood the word, Christian.

We’re speaking in an election year, where the majority of people in the US who identify as white evangelical Christians are expected to vote for Donald Trump. I’m guessing you won’t be one of them.

[Laughs]. The furthest thing from possible. The remotest, the most absolutely unlikely thing that could ever happen, at least within my mortal competence.

Did you always want to be a writer?

I believe I did. From an early age, my brother was always painting and drawing and I was always writing bad poems. Uniformly terrible. And they continued to be terrible until I was old enough to decide that prose was probably my best choice.

I was always sitting around thinking about words. It was like predestination [laughs]. I’m joking.

Do you believe in predestination? You’ve described yourself as a Calvinist, so are you comfortable with the idea God predestined you to follow him?

I don’t think there’s any way in which I could feel comfortable with [predestination], partly because the idea is rooted in an understandable but nevertheless primitive notion of causality – as if we were locked into a determinist pattern. Frankly, contemporary physics doesn’t allow that anymore.

Can you explain that a bit more for anyone who isn’t as well-read in physics?

In the past, people thought that if you knew what was happening in one moment, you could project forward. But it turns out that there’s a great deal of play in reality. They call it the decoherence of probability. This implies the faithfulness of God – that he creates continuously in ways that are free in theory, but determined by his loyalty to our creation. In other words, God is free, which I think is an important concept.

God does what he likes?

No. God has accepted a covenant relationship with human beings that allows him to exercise restraint, and also providence.

Has your theology changed over time?

I think I’ve probably become more universalist. You accept, as a Christian, there are certain boundaries beyond which God’s compassion seems not to reach. But that makes me laugh when I think about it now! I would not do any harm to any creature on the planet. Am I assuming that I am more generous than God? Isn’t that a huge assumption? More or less on that basis, I just assume God loves all the children of Adam. I’m content with that. I feel as if another construction might insult God, and that’s something I would be happier to avoid doing.

If we define universalism as the belief that ultimately everyone is saved, that’s a very contentious position in a lot of churches. Are you convinced on this matter, or do you hold a softer version of it, along the lines of ‘I hope God’s love and grace might extend further, but I can’t be sure’?

Well, it’s like when people ask me about heaven – I have no conception of heaven, I simply trust that the word corresponds to a reality.

I can’t be in the position of judging the ultimate intentions of God. I think that is above my paygrade. What Christianity implies to me in that context is an appropriate humility.

It’s true there’s much we aren’t told. But some would argue when it comes to eternal life, we have been told. For example, John 3:16 says “whoever believes” in Jesus “will not perish, but have eternal life” – the implication being if you don’t believe, you aren’t saved. It’s hard to argue universalism from John 3:16, isn’t it?

The whole idea of judgement, which I believe in, nevertheless, is used so viciously in Christian history, that we tip one’s hat to it as it passes by, but basically, it’s not our business.

As regards to John 3:16, if you say: “Everyone who is 18 years old can vote”, that doesn’t mean that people who are blind cannot vote. I think [John 3:16] is an appropriate description of people in a certain category.

When the rich young ruler comes to Jesus and says: “How can I have eternal life?” Jesus says: “You know the commandments”, then he ticks them off. [Jesus is] obviously not excluding him on the basis of his very conspicuous pious Judaism. The fact that you can assure something to one category of people doesn’t mean that you deny that to others.

Do you ever think about what heaven might be like?

You look at the arbitrary features of the world, like liquid water, and people [speaking a] multitude of languages, and there is no circumstance in which I would be able to imagine any of these things if I did not know them and see them. I have to assume, by extension, that I can’t imagine the world I have not seen either, and I’m content with that.

It is not characteristic of God to create any kind of reality that is at the level of my comprehension.

Should we expect a follow-up to Reading Genesis? Could this be a commentary series on every book of the Bible?

No. I’m 80! I’m a realist! Even predestination has a terminating date, I think.

But I am writing a book on Exodus, and it depends on how long I dwell in that, but I anticipate looking at the other books attributed to Moses.

I am very pleased to have been able to reintroduce the Bible into conversation. In my career, I’ve been able to test, over and over again, the assumption that there is an impenetrable dismissiveness towards religion. Absolutely not in my experience! One of the things that can be offensive about people who call themselves Christian is that they’re in this defensive crouch, always acting like somebody else is going to be unfair and antagonistic. That’s a very bad look, and so remote from my experience.

You’ve been awarded some of the highest prizes in literature, and much of your work has an obvious Christian theme. You’re saying it has not held back your career in any way?

I think that’s fair to say. I have tested people’s generosity and I have found that they are very generous.

Do you have any goals when it comes to your writing and the impact and influence you might have?

I have no idea how much or how little any of my books sell…

You genuinely don’t know?

I don’t know. I’ve never asked. I’m perfectly content. I can pay my bills. Everything is OK.

You do what you can. You put the note in the bottle and drop it in the sea. But my books have done well – perhaps better than I or anyone else would ever have expected.

My books have done better than I or anyone else would ever have expected

Do you ever think about how you’d like to be remembered?

I don’t draw on personal biography, and I don’t like it. I don’t believe it when I read it. I have seen certain things that people have written about me and never, ever do I have a moment of recognition of this as myself.

The Atlantic described you as “one of the greatest living Christian novelists”. Is that the sort of thing you’re talking about?

I don’t consider that biographical. I consider that critical.

OK. But there are facts about you which are true. Where you were born. How tall you are…

Insofar as it can be factually affirmed, it is not wrong. But it’s like a character – you can know all kinds of facts about him or her, but if it isn’t reimagined as a human self, these are simply irritating pieces of information.

I can imagine 50 different Marilyn Robinsons fitting themselves into my skeletal biography, every one of them more irritating than the last.

Are you saying that a person writing a biography rarely gives a full sense of the person?

If they don’t get the sense of you, it’s just not you.

Have you ever thought about writing an autobiography?

No. I don’t believe myself any more than I believe anyone else!

So the problem isn’t the person writing the biography, it’s simply the attempt to do it?

Exactly. There’s so little we know.

To hear the full interview listen to Premier Christian Radio at 8pm on Saturday 20 April or download ‘The Profile’ podcast premierchristianity.com/theprofile

No comments yet