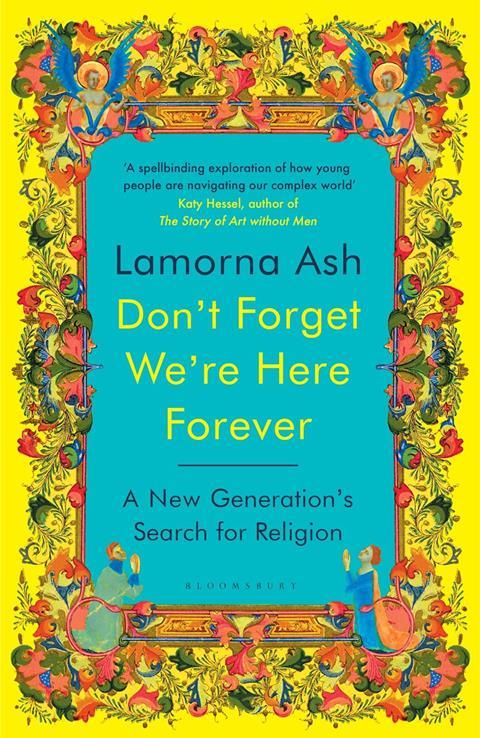

The author of the critically acclaimed book Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever spent a year trying Christianity Explored, Iona retreats and Quaker meetings in an attempt to find faith for herself. She shares the highs and lows of her spiritual journey so far with Derek Walker and explains why an evangelical view of sexuality will always be a barrier for her

After two university friends simultaneously and unexpectedly came to faith, award-winning author Lamorna Ash was intrigued enough to spend a year researching Christianity’s appeal to the younger generations.

As part of this she didn’t just interview Christians of all stripes - she explored faith for herself. Christianity Explored was off putting, but several retreats had a profound effect on her.

The resulting book, Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever, (reviewed here) a spiritual travelogue - tracing her journeys around the country and inside her soul. She began as someone with no real background in Christianity, but found her research changing her more than she could have ever expected.

Your journey began when you discovered your comedy double-act friends had both converted to Christianity and wanted to become priests. What was your reaction?

It was a mixture of things: surprise – back then, I didn’t think I had a single Christian friend (now I know that some of my friends had been quietly attending church or calling themselves Christians for years; they just didn’t publicise it among their more sceptical, secular friends); suspicion – I had a very primitive conception of Christianity, presuming that it required all new believers to align themselves with various kinds of what I believe to be regressive patriarchal, sexist and homophobic, social and political positions.

Perhaps most importantly, though, I was fascinated!

You had already been confirmed - so you weren’t completely new to church. Is that right?

In practical terms, we went to church once a year on Christmas.

Outside of that, I knew as little as it could be possible to know about Christianity for much of my childhood.

The outlier to all this is that I decided to get confirmed at 14. At the time, I described this decision to my bemused friends as a ‘preventative measure’, in case I one day needed faith. It was mature in that I recognised there was something serious and inarguably meaningful about Christianity, but immature because there was an inherent flippancy colouring the decision.

You didn’t enjoy the Christianity Explored course that you tried. I get the impression that if you weren’t committed to your research, you’d have turned away then. What was it like to be angry, but still see a glimmer of something deep and real to all this?

Confusing! It felt hard to square the discrepancy – what I was hearing from the pulpit [was] mostly tired dogma infused with lots of homophobia, expressed as if Christianity were not an endlessly complicated form of belief, enriched and deepened by a long, dense, nuanced history of serious theological thought, but was instead a narrow and contemporary-informed set of prosaic rules, mostly related to sex and so-called ‘culture wars’ topics.

What I was discovering through reading Mark’s Gospel among the other young people on my table [was] how strange and ambiguous that text is, how remarkable and radical Jesus Christ appears out of its narratives, how unusual and particular each individual’s expression of faith was compared to the apparent voice of authority at the pulpit, telling us there was only one way to talk about God and Christ.

It was also galvanising. That frustration made me want to look further into the Christian faith, to discover the myriad ways people might respond to Christ’s teaching, across as many denominations as possible. More than that, it made me want to continue exploring Christianity in my own right, because I was rapidly learning how much more there was to the religion than I had naïvely assumed. I guess that’s the beauty of Bible studies, that each person is going to have their own relationship with those ancient parables, stories and lessons, which might then lead them to all kinds of places.

What were the main stages of your antagonism melting away?

It was down to the Christian retreats I attended and the Quakers.

I relate the Christian retreats I went on – on the Iona in the Inner Hebrides, in Walsingham one Easter, at a Jesuit retreat in North Wales – to the wilderness periods undergone by various figures from the Old and New Testaments. Sometimes you have to take a step away from your ordinary existence in order to travel to where it is still and quiet and maybe even more holy, so as to then work out where you are going wrong or what is missing from life.

After your wilderness period, you return to your normal, mundane life with newfound clarity and a sense of purpose. A Quaker meeting offers something similar.

After my period of attending Quaker meetings, I started attending (semi-regularly) a very unassuming, progressive Anglican church, with a beautiful choir and an eclectic congregation. I don’t think I could have turned up there right at the start of my research. I think I needed to embark on a journey through other forms of Christianity first.

How has developing faith affected your lifestyle and character in practical, objective ways?

I am still in such a tentative, exploratory moment with regards to my own faith that it feels hard to offer anything definitive.

But I know that I find the ritual of attending church helps to slow me down, bring me peace and makes me more attentive to the wider world. I know that I am so grateful to have discovered this loving and eccentric second community through church. I know that, practically, I now have a place where I can go to attempt prayer and to sit with my grief.

Practically, I now know so much more about Christianity’s history and the Bible, which means I think I understand our contemporary world and its roots far better than I did before.

You write, “By 26, I’d inherited all these unquestioned assumptions about Christianity”. For your generation, how much of a barrier do you think these cultural norms are to exploring faith seriously?

I think mainstream contemporary assumptions about Christianity function as a huge barrier to people wanting to explore the Christian faith. If you have heard that Christianity is a religion which, as an institution, rejects queer people, excuses paedophiles and is structurally sexist – just as some examples of the things I thought, and the things I hear others say, about the religion as it plays out in Britain today – then you are not going to want to step towards such a religion.

There are many other barriers. You might find it impossible to imagine believing in something as strange as the resurrection, or that Christ is the Son of God. It might be that the Christian faith doesn’t interest you because you are able to find meaning, community, purpose in other places. It might be a combination of all three.

I think my generation is starting to question those black-and-white assumptions because we have grown up in a more pluralist and diverse world which (not always, but often) makes us more tolerant of those who have religious beliefs. Sometimes I think the prevailing mood of our generation is one of doubt: there is so little we can be certain about when it comes to our own future and the future of the planet. The New Atheists were not all that into doubt; everything seemed provable and understandable. Doubt is a more useful frame of mind in which to approach faith.

You recall CofE school assemblies and note that exposure to Jesus’ death and resurrection “had become something which seemed… oddly banal.” How much do you think our introduction of Christianity to children inoculates them against it? How would you change it?

I think we should let young people engage with the Bible as they might with any other work of literature – let them wrestle with it.

I think we need to take young people’s intelligence and capacity to deal with challenging, complicated things very seriously. It would be great for young people to read and write about holy texts from every religion, to compare them. We should encourage them to question as much as possible. Religious and philosophical texts might give them the tools to better deal with the world as they approach adulthood.

You were somewhat scathing about Conservative Evangelicals. After the rest of your research, do you now find anything in their approach that you can identify with?

I think there is beauty and value to be found in all forms and denominations of Christianity – as well as possible harm. I respect how Christians of all flavours attribute their ethics and morality to their faith – their attempts to be humble, merciful, to question power and the trappings of wealth, to protest against war, to love one another, especially those who seem most different from them.

That moniker ‘conservative’ often means in practice, however, where such leaders stand on issues of sexuality. I will always speak out against those Conservative Evangelicals who believe and broadcast their belief that it is a sin for queer people to have sex. Often they will say that they love the queer community but that it is a sin for gay people to enact their desire as straight people do. Such a statement does not hold together.

I have found so many [better examples]. Some are priests who say the most extraordinary and brave things during their sermons. Some Christian leaders I have found are members of the laity who tell me that their faith and their analysis of the gospels has led them to become social workers or to found charities or to make music or art or poetry. I admire the British Quakers’ total commitment to justice, peace and equality, cultivated through silence and then acted out through protest and deeds. The same goes for the young people I have met from the Catholic Worker movement who provide hospitality for and live together with asylum seekers and refugees. These spiritual leaders I meet, they do what they do for the world because they feel called to such actions by the teachings of Christ.

Don’t Forget We’re Here Forever (A New Generation’s Search for Religion) by Lamorna Ash (Bloomsbury Publishing) is out now

No comments yet