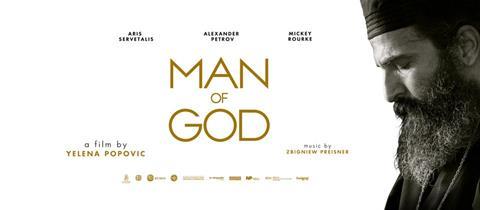

Starring Mickey Rourke, Man of God tells the true story of Saint Nektarios of Aegina, exiled unjustly, convicted without trial and slandered without cause. The film is a fascinating insight into the Greek Orthodox Church, says Giles Gough, even if the dialogue could do with some work

Written and directed by Yelena Popovic, Man of God tells the story of the widely venerated Saint Nektarios of Aegina, a Greek Orthodox priest who rose to prominence in the early years of the 20th century. Unjustly relieved of his position in Egypt and the target of baseless slander by his fellow priests, Nektarios (played by Aris Servetalis) returns to his native Greece, to be told that not only are there no positions available for him, but that he is no longer a Greek citizen. Still, Nektarios continues to struggle on, preaching the word of God and helping the poor and downtrodden whom the Church have widely ignored.

From the opening titles, this story lets us know that it is going to be a Very Worthy Film Indeed. Dressed in the robes of his office, we are introduced to Nektarios walking through the streets of Cairo. The camera stays resolutely on his back in a way that evokes Rourke’s other film, The Wrestler, and perhaps gives a clue as to the downbeat tone.

Stating the obvious

Thankfully, the plot wastes no time in getting going. Within five minutes, a group of rival priests are scheming against Nektarious. They fret about him becoming the next Patriarch (the leader of the Greek Orthodox Church). “He consorts with harlots on the streets” one priest says. When he adds: “He would give away every last penny we have to native Arabs and beggars”, it becomes clear that if, this priest actually read the Gospels, he may be in for something of a shock.

Showing the religious leaders plotting against him means that the parallels between Nektarios and Jesus aren’t so much clear as screamingly obvious. Which is a complaint that could be levelled at the rest of the film. It all feels perfunctory. The writing, the acting and, at times, even the filmmaking feel a bit…basic. In contrast, some of the cinematography is absolutely beautiful, to the point where it draws into sharp relief the areas that are a bit more lacking.

Light relief

A lot of what makes the film a difficult watch is the central performance. Aris Servetalis portrays Nektarios with very little light and dark. Many of his lines are delivered in a flat monotone, which isn’t helped by the writing; in every scene, without fail, he says and does the right thing. Nektarios was canonised in 1961 so it’s probably odd to complain that a priest seems a little too holy when the man is a literal saint. But it wouldn’t hurt to show the character in an attitude of something other than solemn humility. Perhaps some evidence of laughter, desperation or a greater show of frustration might have helped. Even in The Passion of the Christ, Jesus managed to get in a few laughs. The central performance might remind some viewers of a line from Kevin Smith’s Dogma, where an angelic being tells a human character: “You people don’t celebrate your faith, you mourn it.”

The parallels between Nektarios and Jesus aren’t so much clear as screamingly obvious

But if one flaw stands above the rest in this film, it is the supporting cast. At one point, one priest berates another by saying: “Thank God you are not an actor,” which is an odd line, as not being able to act does not appear to have been a barrier to appearing in this production. Supporting characters are all too eager to give away crucial plot information, or spout clanging, anachronistic lines like: “You seem to be the real deal”. A lot of the dialogue feels like it needed another pass or two to polish it up, and that’s before we get into the poor man / disability tropes that make many of the characters feel less like people and more like non-playable parts.

Looking in

All that said, this is not a film without redeeming qualities. Towards the end of the run-time, you do begin to sympathise with the character (although at this point it may be something more akin to cinematic Stockholm Syndrome). But if there’s a line that lingers in the memory, it’s when Nektarios says: “When you are persecuted, the right thing to do is to turn another cheek. But when your children are persecuted…the right thing to do is to fight”.

For all its flaws, Man of God does give us some insight into the culture of the Greek Orthodox Church in the early 1900s, a world that many viewers may be unfamiliar with. Nektarios was undoubtedly an utterly devoted man of God, but whether his life makes for compelling dramatic fodder is quite another question.

Man of God is on a limited run at UK cinemas now. Find out more at: facebook.com/manofgodthemovie

1 Reader's comment