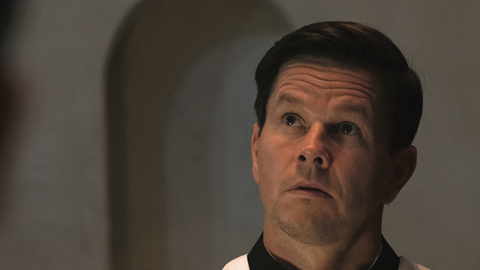

Your enjoyment of Father Stu is contingent on your tolerance for both bad language and Mark Wahlberg, says our reviewer. Nevertheless, this movie does mark a positive step forward in the evolution of Christian filmmaking

Christian cinema – the corner of the industry that makes films exclusively for faith-based audiences – has enjoyed a modest amount of success among its target demographic. Films such as God’s Not Dead and Fireproof have resonated with Christians who are, understandably, a bit tired of a culture that seems at best disinterested in faith or, at worst, actively hostile towards it. Yet such films never cross over into the mainstream, rarely gaining a wider audience (except for a few cynical ‘hate-viewers’) and do poorly with critics. Snobs like me, who go to the cinema looking for satisfying art, are often left unimpressed. Now, with Father Stu, Mark Wahlberg is trying to change that.

Wahlberg, an actor perhaps best known for muscular action films and dumb comedies, has put a considerable amount of his personal money, not to mention his box office appeal, into this passion project – the story of a charismatic, foul-mouthed boxer who becomes a Catholic priest. And he has roped in Mel Gibson – also a proponent of bigger budget, macho faith-based movies – in an attempt to create something that will appeal to a wider audience while still having an inspirational Christian narrative at its core. Has it worked? Well, sort of…

AMERICAN STU

The main criticism you could level against the Christian film industry is its lack of authenticity. Rarely do the characters in these films feel like real people; instead they are caricatures that the writers use to make a point. It’s hard to invest in the drama of a film like God’s Not Dead when the performances and dialogue are as wooden as a Hallmark Christmas movie, with a plot that is just as predictable. With a target audience who just want to watch something they agree with, it’s easy for faith- based films to put in minimal effort without ever challenging the audience to empathise with real, gritty or difficult situations.

Father Stu is undeniably a departure from this model. From the moment you meet Stuart Long, his face bloodied from a boxing match or swearing down the phone at his dad, he immediately feels like a more credible human being than the cookie-cutter figures you might expect from a typical ‘Christian film’. Wahlberg had to fight to keep the bad language in the final edit, even arguing with some Christians who didn’t want him to swear while filming in their church building. Indeed, the anticipation of bad language is enough to put off many potential viewers, but after years of film criticism, I’m sadly inured to it. Your tolerance may vary.

MOST OF THE WORLD IS RELIGIOUS, YET AMERICAN AND BRITISH CINEMA LARGELY IGNORES ANY MENTION OF FAITH UNLESS IT’S THE BUTT OF A JOKE

Yet Wahlberg’s argument is that the real Stuart Long – a raggedly determined, salt-of-the-earth type who grew up in Montana – was a guy who swore, fought and slept around, before a near-death experience after a motorbike crash led to his dramatic conversion. The drama of the story lies in the difference that this conversion made to Stu’s life. The result is something that does feel a bit more realistic than the usual Christian fare.

Wahlberg is not the best actor in the world, and he won’t win an Oscar for this role, but his dedication to the film does pay off. He put on weight for the role, spent time with Stu’s real family and fought for the story to be told authentically. By giving the film a bit more budget and some much-needed star quality, he automatically elevates it to something far more watchable than most Christian films.

OVERCOOKED STU

Even so, it struggles to land much of an impact. In part, this is down to the sprawling nature of the narrative, covering his time as a boxer, his brief career as an actor and his conversion, before ending with the decline of his health and his becoming a priest. Throw in a poorly explored romantic subplot and you get just one too many ingredients in this ‘Stu’ for any of the flavours to really stand out.

The writer and first-time director, Rosalind Ross, struggles to bring focus or dramatic heft to Stu’s journey, failing to even establish a clear era in which the film is set (1970s? 2000s?). Mel Gibson (Ross’ partner) plays Stu’s cantankerous, detached dad, the source of many of Stu’s problems. This dramatic invention (by all accounts, Bill Long is a good man and a loving father) wouldn’t be so bad if it improved the film, but instead it becomes just another loose thread in an already baggy narrative.

The stakes, for much of the film, are curiously low. Stu’s interest in the Church emerges because he falls for a woman who comes into the shop where he’s working. She seems to like him too, for no discernible reason, but their tepid romance never grips in the way you’d hope. Will she discover that he’s faking his faith at first, or notice a change in him when he genuinely becomes a Christian? In the end, it doesn’t seem to matter. He finds Christ, and decides to become a priest. Even the obvious tension of the requirement to be celibate leads to only one semi-argument before she capitulates.

One of the most egregious moments of dramatic inertia is perhaps the most important turning point in the film. Stu crashes his motorbike and gets hit by a car. On the verge of death, he has a vision of the virgin Mary in which he has a brief conversation with her. The moment feels mundane rather than transcendent – perhaps the effect was dampened on this Protestant viewer who venerates Jesus’ mother less than Father Stu does. But the next day, even Stu doesn’t seem to really have been impacted; he’s still his cheery, overly talkative self, with no noticeable change or sign that he needs to process this heavenly visitation. There are no real highs and lows in Father Stu, just a greatest hits compilation of the man’s life. And some of them are made up.

FINDING MEAT IN THE STU

This is not to say that Christian viewers will get nothing from the film. It seems as though Stu was indeed a remarkable man whose ministry touched many lives in his local area. The strength of his story is enough to provoke some discussion and response from an engaged viewer. In particular, the final third of the film, which charts his decline due to a degenerative muscular disease, caused me to stop and think about suffering, grace and service to God.

The central appeal of the story is that Stu is someone who is rough around the edges, setting foot in church for a whole host of the wrong reasons. He is, the film posits, one of the last people you would expect to become a priest. His story might provoke us to consider who, in our own lives, might be similar diamonds in the rough.

Are there people we’ve discounted because of their background, their job or their reasons for being in church? I know I’ve written off people like Stu in the past. Perhaps, in doing so, we are missing out on the fruitful ministries of people we assume could never end up in a pulpit. The real Stuart Long touched hundreds of lives, ministering to people every day in his care home even as his health declined. God had a plan for him and it was only his cheerful determination not to let anyone dissuade him from chasing that plan that led to his ordination.

Sadly, the film misses out on a lot of this rich dramatic material, but it nonetheless manages to capture some of the grace that Long discovered in the latter years of his life. I wanted to see more of the ministry that came after he was diagnosed with this degenerative disease but, instead, Father Stu treats Long’s ordination as the finale, not the beginning of his most fascinating chapter.

The same determination that kept Stu boxing well past his prime, that got him acting jobs with no experience and opened doors into seminary, is the same determination that helped him to press on with ministry even when his body was deteriorating. There’s a refreshing simplicity to his faith; he knows his calling and he isn’t going to let illness stop him from fulfilling that. This is the meatiest part of Stu’s story and the film could have been much more powerful if this was the focus.

THIS FILM ISN’T AFRAID TO SHOW A MESSIER SIDE OF HUMANITY

Even if you tune out towards the end – two hours is a bit too long for a drama of this kind – it’s hard not to be moved by his devotion to ministry. Unexpectedly, I found myself reflecting on my own attitudes to suffering and how self-centred I can become when faced with poor health. Witnessing someone have it far, far worse and still doggedly serving God is enough to cause anyone to stop, ponder and pray.

A SECOND HELPING OF STU?

Father Stu is unlikely to gain too much traction among non-Christian audiences. It has received lukewarm reviews so far, and the casting of Gibson (accused of battery by a former girlfriend and who, on several separate occasions, has made anti- Semitic, racist and homophobic comments) may be enough to put off many viewers. But it could do well enough to be the first step towards a more thoughtful approach to faith in cinema. After all, around 85 per cent of the world identifies with a religion, yet American and British cinema largely ignores any mention of faith unless it’s the butt of a joke. The Christian film industry’s response has been woefully insufficient so far, with the most spiritually invigorating films often being lengthy, theologically ambivalent arthouse releases. There’s undoubtedly a gap in the market for more mainstream Christian cinema.

Father Stu tries to be both accessible and Christian, and it just about passes muster. It’s an admirable attempt, but still falls short of being a truly successful Christian film. What the film gets right – and what other Christians in the industry should be seeking to emulate – is that it isn’t afraid to show a messier side of humanity. Cinema is a vehicle for empathy and we, who have all experienced the grace of God even at our weakest, should be the most empathetic of all when watching the weaknesses and struggles of others on the big screen. If Father Stu can push Christian artists away from simplistic characters and trite storytelling towards something a bit more real, then cinema will be all the better for it.