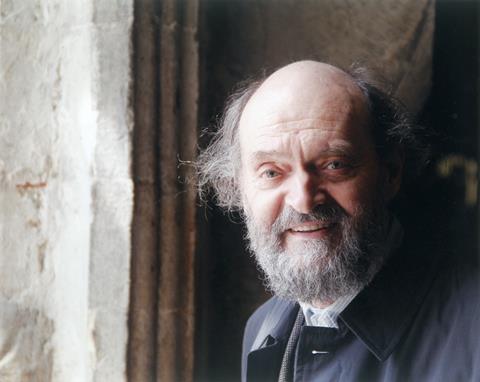

Arvo Pärt, the world’s most-played living composer, is 90 today. Derek Walker explores how his deep Christian faith shaped his globally celebrated compositions - and why his influence endures across cultures and generations

It would be one thing to be the most-played living composer for a year but, remarkably, Arvo Pärt held that record continuously from 2012 to 2018, only dropping to second (behind John Williams) in 2019 before regaining the top spot again in 2022.

It is even more remarkable, considering that Williams’ fame comes from scoring some of the biggest movies of all time - including Star Wars, E.T, Jurassic Park and the Harry Potter series.

This month, the classical music world is celebrating Pärt’s 90th birthday, not just at the BBC (as composer of the week and at The Proms), but in cities across Europe.

One reason behind the Estonian composer’s success is his Orthodox faith, which comes through in what The Barbican called, the “signature blend of purity, stillness, and profound spirituality” of his instrumental pieces, and his choral work, which is based predominantly on Christian texts. Yet that faith has been severely tested over the years.

Early years

Pärt grew up in an artistic household. The piano must have been well-used, as the middle register was damaged, so he would experiment with the top and bottom notes. This may have been the genesis of his key work ‘Spiegel im spiegel’.

He began music school aged seven and went to the Tallinn Music Middle School 12 years later. His studies were interrupted by a conscription to military service, where he played the oboe and drum in the band. When asked why he didn’t play the piano, he commented that if he could carry it around, he would do so. After his service, he studied composition – mainly for film and stage – at the Tallinn Conservatory.

The 1960s were a difficult time for Pärt as he struggled with his musical identity. His work as a sound engineer in Soviet-controlled Estonian Radio gave him clandestine access to tapes that were marked “Not for broadcast”, including works from the West, which helped him to see beyond conservative state-sanctioned styles.

Courage and commitment

1968 was a formative year. Pärt composed ‘Credo’ - meaning “I believe”. The piece placed early music alongside new, representing the idea of good and evil (out of step with the principles of Soviet socialist realism). It was a public confession of faith and based on sacred text – the Creed and the Sermon on the Mount.

Its première was a work of reckless courage and coincidences. The Composers’ Union censors were in Moscow, so missed the rehearsal; the official first hearing took place three months later. No officials understood the Latin text and the conductor, Neeme Järvi, was brave enough to face any consequences. To minimise fallout, no musicians were told of the content or background to the piece, and nothing was noted in the programme or the Estonian cultural magazine that reviewed it.

However, despite a rapturous response from the audience, the piece was banned and Pärt’s work became more closely scrutinised for years afterwards. Pärt was instructed to disavow the piece, but he refused. His son Michael commented that the ban “set him free.”

If he was not going to deny his faith, then he would have to leave the country. So in 1980, his family were exiled to Germany

Just months before the première, Pärt had spoken in a radio interview of Jesus being his most important influence. The interviewer cut that part of the broadcast, but it shows Pärt’s unashamed commitment to his Christian faith. After this episode, Pärt embarked on a process of removing everything unnecesssary in his music, joking that had he removed any more, the result would have been silence.

Crisis and breakthrough

In 1976, after almost a decade of creative crisis, he was leaning over his notebook in despair when a young girl, aged about ten, asked him what he was doing. He replied: “I’m trying to write music, but nothing is coming”. She asked whether he had thanked God for his failure. Pärt says that he understood so much from that girl’s words, which helped him to move forwards.

His Orthodox faith comes through in the signature blend of purity, stillness, and profound spirituality of his instrumental piece

That year, he wrote the seminal ‘Für alina’, a short piano piece. It marked the start of his groundbreaking Tintinnabuli style, which means “little bells”. While it echoes that effect sonically, Pärt uses it to define the larger sound he is after – something clean, pure and simple.

‘Fur alina’ was, in part, written as solace to a friend left behind the Iron Curtain when her estranged husband emigrated with their daughter to the UK. But Pärt has since described it as evoking the moment after confession, feeling cleansed and able to look forwards.

Clear direction

Pärt met his wife Nora in 1972 and converted from Lutheranism to the Orthodox Church that same year. His son Michael considered that Nora’s influence “had a lasting impact to my father’s work…through digesting the wide number of books from early Christianity from the desert fathers, liturgical texts that they were hungry for in the search of exploring their new-found connection.”

Having found the key to his compositions, Pärt became prolific. Some of his music from 1977 includes his most popular instrumental pieces: ‘Fratres’, ‘Cantus in memoriam Benjamin Britten’ and ‘Tabula rasa’. But the international popularity of his faith-centred music gave the Soviet authorities a problem. If he was not going to deny his faith, then he would have to leave the country. So in 1980, his family – with their nine suitcases containing many manuscripts – were exiled to Germany.

Free of state interference, Pärt flourished. He first applied his Tintinnabuli approach to texts with ‘Passio’ (the St John Passion) in 1982, followed by ‘Magnificat’ and ‘Stabat mater’.

That there are two independent fan clubs in Iran says something both of Pärt’s international appeal and his reach across ideologies. ‘Purity’ is a word that is often used in connection with his music, but it also speaks of his integrity. The texts in his music are lived out in his refusal to renounce the God he serves.

Jesus said that if you seek the kingdom of God as a priority, then you need not worry about everyday things. Arvo Pärt’s life and music are a gleaming example - and the world will be celebrating it this month.

No comments yet