Dr Beth Felker Jones believes a now removed article on The Gospel Coalition takes the biblical metaphor connecting God with marriage and turns it into a porn-inflected ode to intercourse

Earlier this week, Tony Wilson responded to social media controversy over a book excerpt by Josh Butler, posted at and now removed from The Gospel Coalition’s website. Butler asked us to see the sexual act as an “icon” of salvation and interpreted sex in terms of male “generosity” and female “hospitality.”

The Butler piece inflamed a firestorm online, and I’ve already named the deep theological problems it raises. Here, I respond to Wilson’s claims that to “cancel” Butler amounts to cancelling Augustine along with the Christian tradition, and that critiquing Butler teaches us “more about our distorted view of sex than the truth of his writing.”

A high view of sex is good, but it does not suggest that a woman who says no to sex is failing in her calling to hospitality

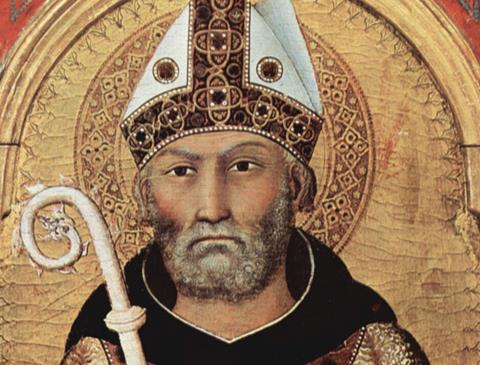

Butler takes the biblical metaphor connecting God with marriage and turns it into a porn-inflected ode to intercourse, interpreting male orgasm as a self-sacrificial gift. Augustine would be horrified.

Exquisitely attuned to the ways sex can be twisted under the condition of sin, Augustine was a pastor, and knew that we humans can take something good - bodies and desire - and bend it into something evil. He knew how easily sex can be used for selfishness, lust, domination, and the exploitation of women. Wilson glosses over the dangers of sexual violence and abuse, writing them off as results of sin, as though those results don’t stalk Christian marriages every day.

Idolatrous allegory

Most of Christian history has read the Song of Songs as an allegory for God’s love for Israel. These days, it’s more popular to read it as a depiction of human love, and some commentators even mock the Church past for being too prudish to read the song more “literally.” But the Church wasn’t being prudish; it was recognising the difference between the Creator and creation, and that overly literal use of the metaphor of human for God would be idolatrous. It was recognising, with Augustine, that we humans often use sex for sin.

Wilson is correct that Augustine uses imagery drawn from sex and marriage, but he then misses the point entirely. Augustine’s use of the imagery is opposite to Butler’s. When Augustine reads the Song of Songs as an allegory for God’s love, he does so aware of the fact that simplistic readings can take us into idolatrous territory, explicitly forbidden by scripture. The Church fathers knew that God is not a pagan, Zeus-like, man-shaped God, and so they knew that the song’s symbolism shouldn’t be reduced to body parts.

For example, Gregory of Nyssa interprets “he shall lie between my breasts” (1:13) as referring to the location of the heart, the center of our being, from which arteries branch out “to the whole body.” According to Gregory, this scripture isn’t about breasts; it’s about God’s presence filling us from the heart and extending from there to the whole body, so the Church can “simmer with the Spirit.”

Respecting the limits

I’m personally convinced the song should be read both as being about God’s love for us and about love between humans, but we should not dismiss the careful wisdom of the Christian tradition in warning us against overly sexual and so idolatrous readings. This doesn’t mean we can’t talk about breasts, which are good because they are created by our good Creator. The song can be about both the goodness of breasts and the way we’re called to “simmer with the Spirit.” But we must take care not to talk of breasts in a way that baptises sinful, porn-inflected views of sex.

The Song of Songs is a romp of mutual delight, with a refrain about the one who is both “lover” and “friend,” and often we readers can’t even tell which of the lovers is speaking. We certainly can’t sort the bits of it into male “giving” and female “receiving.” There’s good reason Christian history has been careful about the marriage metaphor: scripture does not forget that metaphors have limits. Metaphors for God must always respect the limit of God’s transcendence and otherness from creation, lest we fall into idolatrous paganism.

The problem with Butler is not in using scripture’s marriage metaphor but using it in unbiblical and harmful ways. In Hosea, the marriage metaphor is used to emphasise God’s faithfulness to us, not to describe God as a human male with genitals, and not to associate males with God in a way that females are not. Marriage is a metaphor for God (a beautiful one that does bless human marriage and sex), but the metaphor does not tell us what Butler or Wilson suggests it does. Scripture always maintains mystery, not a clumsy phallic literalism which underwrites power asymmetry between men and women.

Upending our assumptions

Butler ignores the complicated and interesting ways in which the analogy between married partners and Christ and the Church actually works. The said analogy does bless gendered difference, but it also upends our gendered assumptions by immediately gendering every single human being as feminine. In this metaphor, males are feminine, females are feminine, every human who is part of the body of Christ is feminine. And that’s a challenge to toxic masculinity, both ancient and contemporary, just as the male Jesus is a challenge to the same.

The Church fathers knew that God is not a pagan, man-shaped God, so the song’s symbolism shouldn’t be reduced to body parts

The metaphor is powerful. It trades on the good reality of human desire, but it also relativises sex in light of the desire we were made for, that we should know God. Critique of Butler is not squeamishness about sex. The problem with Butler is not that he dares to talk about genitals. It is that he speaks falsehoods about them.

Wilson is right that Christians should not denigrate sexuality, as sex is a good gift from God and part of the goodness of his creation. But this is the reason Christian sex talk cannot mean that anything goes. A high view of sex calls sex good, but it does not borrow from porn, elevate patriarchy or suggest that a woman who says no to sex is failing in her calling to hospitality.

Augustine knew that we’re a sinful mess, and we should heed his cautions. While Wilson claims Butler has been “cancelled,” his book is still climbing the presale charts and is set for publication, with no word from the publisher about the theological disaster it may bring.

No comments yet