Pastor and author Joshua Ryan Butler may not have formulated his ideas about sex as carefully as he might have done, but he is certainly on to something profoundly Christian that has a long and rich heritage, says Tony Wilson

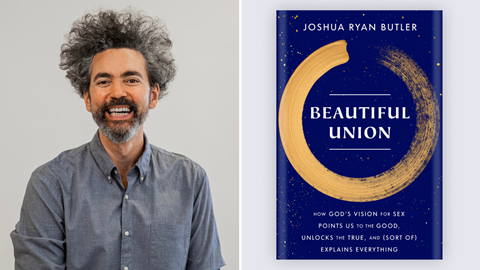

Anyone connected to Christian social media in the last week will have read about the storm surrounding a new book, Beautiful Union, by Joshua Ryan Butler. In essence, it explores the idea that the sexual union between a husband and wife is an icon of our salvation through Jesus.

Extracts published online by The Gospel Coalition (TGC) were hastily taken down following outrage on Twitter. TGC later apologised for the “hurt” caused and Butler stepped down as a Keller Center fellow. In other words he has been ‘cancelled’.

The language Butler used left some readers with the impression that sex incorporates male domination over women and, if this was his intended meaning, it is right we call him out. However, the book’s blurb suggests the work is in harmony with Christian orthodoxy right back to the Early Church Fathers – and I have to say I agree.

Sex and St Augustine

In The City of God, Saint Augustine made the link between the sexual desire expressed in Song of Songs and our salvation when he wrote: “But this pleasure is wrapped up in allegorical veils, that the Bridegroom (Jesus) may be more ardently desired, and more joyfully unveiled.”

Again, Augustine in a sermon told his listeners of the “marriage bed of the Cross on which our salvation was consummated.” In fact, a better translation of the last words of Jesus might be: “It is consummated.”

Similarly, St John Chrysostom, born in 347 and Doctor of the Church, prepared candidates for baptism by telling them they were about to take a nuptial bath.

Saint Mechtilde, a German charismatic of the 13th century, echoed the same idea when she wrote that Christ’s “noble nuptial bed was the very hard wood of the Cross on which he leaped with more joy and ardour than a delighted bridegroom.”

If we find ourselves getting a little uncomfortable with these analogies then we might need to recover a high view of sex within marriage.

By ‘cancelling’ Butler and pouring scorn on his work we learn more about our distorted view of sex than the truth of his writing. Have we absorbed such a fallen and distorted view of intercourse from our culture that we have an impoverished vision of the intimacy God calls us to?

Jesus the bridegroom

The Bible starts with a marriage and it ends with the marriage of the Bridegroom (Christ) and his bride (the Church). It has a love poem about marital sex in the middle (Song of Songs) that some earlier Christians considered so erotic it was unsuitable for children to read.

The language of arousal and ecstasy was not lost on the Early Church Fathers whose commentaries on the Song of Songs link these themes to the longing that can only be satisfied in Christ.

So, on the face of it, we have to say that Butler is on to something of value.

Jesus calls us back to our original innocence about sex in his discourse with the Pharisees recorded in Matthew 19:8, and Paul joins the dots in Ephesians 5:31-32. But it is natural that we import some of the brokenness of our own sexuality when we think in these terms and, of course, the analogy with God breaks when we do so.

But before the Fall there was no shame. Our first parents didn’t need clothes because they didn’t lust for each other. The tragic domination by men of women didn’t yet exist and so they could expose themselves to each other without the risk of being treated as objects. The domination and objectification of others is a consequence of the Fall and so ‘fig leaves’ became a necessary protection against lust.

Having lost our original innocence, we all feel distinctly uncomfortable thinking about sexual intimacy as an icon for the non-sexual union that God calls us to. The very fact that God has gifted us with such a powerful sexual urge is, in the words of Christopher West in his “Introduction to the Theology of the Body”, meant to give us rocket boosters to find our ultimate joy in him for eternity. The tragedy is that we all share in the lie of the Fall – and our rockets frequently guide us to self-destruction.

Critics accuse Butler of portraying male sexual domination. To this extent he distorts the iconic and sacramental nature of the act. The more biblical perspective is one of self-donation. Jesus said: “This is my body given for you” and every husband should also offer his body in a self-sacrificial way to his wife. The self-donation of the man and the receptivity of the woman are indeed icons of the Church as the bride of Christ receiving her Bridegroom in salvation.

The traditional Christian insistence on the complementarity of male and female within marriage has nothing to do with historical social norms or oppressive patriarchy. Nor has it anything to do with the Church failing to keep up with modern life. It is because the iconic sign must point fully, freely, faithfully and fruitfully to the complementarity of a self-given saviour to whom we must be receptive.

If sex is expressed in a way that is not full, free, faithful and fruitful we have set our rocket boosters in the wrong direction and we tell lies with our bodies about God to the society around us. So the stakes are high and we all have to repent that our brokenness has caused our iconic signs to point the wrong way. Not one of us can take the moral high ground in this respect.

Josh Butler may not have formulated his ideas as carefully as he might, but he is certainly on to something profoundly Christian that has a long and rich heritage. We urgently need to recover a high view of sex so that we can properly celebrate its sacramental value, pointing the world to the God who loves us without limit.

1 Reader's comment