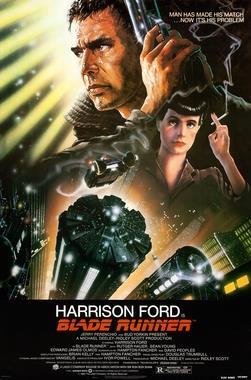

The biblical narrative is so deeply ingrained in human nature that we can find echoes of its story wherever we turn, says Giles Gough. Here, he digs deep into Ridley Scott’s enduring sci-fi masterpiece to look for a Christian message

August marks 40 years since Ridley Scott’s cinematic masterpiece, Blade Runner premiered in the UK.

The sci-fi noir, based on Philip K Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, centres on former police officer, Rick Deckard. Set in a dystopian future in Los Angeles, Deckard is a ‘blade runner’, tasked with hunting down bioengineered humanoids known as replicants and terminally ‘retiring’ them.

Initially underperforming at the box office, it has, in the years since its release, become a cult classic. In 2004, a poll of 60 eminent world scientists voted it the best science fiction film ever made. Now a stalwart of film making syllabuses the world over, students and academics have been dissecting the film for extra layers of meaning.

In the final confrontation, the gospel parallels become almost unescapable

But one layer that has not quite had the focus it deserves is the biblical parallels in the film, which are subtle but undeniable. It would be impossible to go into all of them here, so let’s focus on Roy, the film’s central antagonist.

Fires of orc

When replicants Roy Batty (memorably played by Rutger Hauer) and Leon arrive at the eye lab run by Hannibal Chew, Roy says: “Fiery the angels fell; deep thunder rolled around their shores; burning with the fires of Orc.”

One might be forgiven for thinking that this is a quote from Revelation, or perhaps Milton’s Paradise Lost. It’s actually a misquote from British poet and artist, William Blake. (In Blake’s actual poem, the angels rise from the fires of Orc rather than fall). Blake was a Christian (albeit an unconventional one) and among his works he created a mythology that was a blend of allegory and prophecy. The character of Orc, who appears in some of these narratives, apparently represents rebellion. By referencing this, Batty is identifying himself as a rebel and an angel, a combination that will lead many viewers to one character: Lucifer.

Lucifer was the highest of all angels, the anointed cherub, the most beautiful of all of God’s creations; but he was not content in his position. Instead, Lucifer desired to be God, to essentially ‘kick God off his throne’ and take over the rule of the universe. God did not take well to this idea, and Lucifer was cast out of heaven along with all the angels that had rebelled with him. Biblical references to this pre-human history event are scant (although Isaiah 14:12-15 and Ezekiel 28:12-15 are good places to start).

When the replicants finally meet their creator, Tyrell, we see a version of angels meeting their maker. This is something you won’t find in the Bible, but you will definitely find in Paradise Lost, arguably the best piece of Christian fan fiction ever produced. Tyrell might be an atheist’s idea of God - proud of the replicants but cold, detached and largely ambivalent about their fate. Tyrell’s death at Roy’s hands drifts closer to Nietzsche’s idea of God, who famously said: “God is dead…and we have killed him”. But the rebellious angels comparison falls apart towards the end of the film, to make for another entirely compelling angle.

Batty’s sacrifice

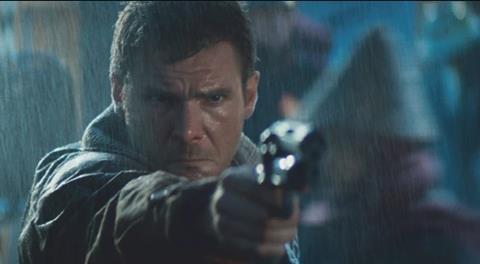

In the final confrontation, the gospel parallels become almost unescapable. By this point, Deckard has killed (or ‘retired’) all the other replicants and is caught in a fight to the death with Roy. When Deckard is left dangling from the roof of the building, Roy appears to have the upper hand - until he reaches out and pulls Deckard to safety. In a moment, Roy goes from trying to kill Deckard to saving him.

Why does he show mercy to the blade runner who has killed all his friends, is trying to kill him and, for all he knows, will keep on killing long after Roy has died? Roy’s last act has subtle echoes of the crucifixion. As Jesus is being mocked and insulted, he said: “Father, forgive them, for they don’t know what they are doing” (Luke 23:34). One of his last acts before his death was to show empathy for the very people killing him.

The Dove

Roy then delivers the classic ‘tears in rain’ speech where he reflects on how all his experiences will be forever lost when he dies. His last act is release the dove he’s holding, and there’s the memorable shot of it flying up into the scarce daylight. At Jesus’ baptism, the Holy Spirit is said to have descended upon him “like a dove” (Matthew 3:16). Doves have come to represent peace but, in this scene, it’s easy to see that the dove is meant to represent the human soul. The dove taking flight implies that Roy’s soul is leaving his body, which, as Roy is a machine, is a fascinating concept.

Blade Runner is arguably the Hamlet of cinema. It’s an incredibly rich text that leads itself to multiple interpretations, including rewarding postmodern, Marxist and feminist readings of the film to name a few. While not explicitly Christian, the biblical narrative is so strong, and so deeply ingrained in human nature, that it can be fun to find it in works like Blade Runner that are entirely secular. Who knows what other interpretations we’ll find in it in the next 40 years?