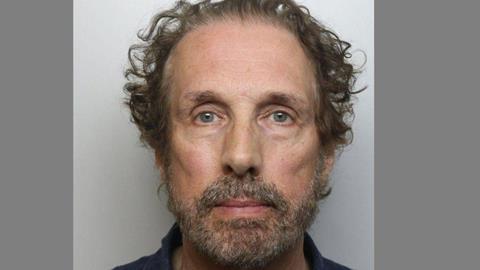

Chris Brain, leader of the now-disgraced Nine O’Clock Service (NOS) has been convicted of multiple counts of indecent assault. It is the latest scandal to rock the CofE and once again poses questions around complaints that were ignored for years

The head of a pioneering church movement in the 1980s and 90s has been convicted of sexually assaulting multiple members of his congregation. Chris Brain’s Nine O’clock Service (NOS) was hailed as revolutionary by the Church of England at the time but later collapsed amid accusations of misconduct – which decades later have led to Brain’s convictions.

In 1986, Brain – then lead singer of a Christian rock band – started a new church service at a large charismatic evangelical church in Sheffield called St Thomas Crookes. It met late at night and soon became known as the Nine O’clock Service or NOS.

Not your usual church service

NOS was nothing like the other services taking place at St Thomas’s - or anywhere else. It is best described as a kind of nightclub-style fresh expression of church, although this was years before anyone had ever used the term ‘fresh expression’. It blended elements of rave culture (techno music and strobe lighting were common) with worship and activism, and drew hundreds of young people, many of whom had little previous church background.

As NOS grew rapidly it drew admiration from church figures all the way up to the then-Archbishop of Canterbury, Most Rev George Carey. Brain was praised as a trailblazer, forging a new church for a new generation.

The flaws exposed by Brain’s conviction raises questions about the current crop of radical church plants

By the early 1990s, Brain was being fast-tracked towards Anglican ordination (despite the misgivings of some of those in the local diocese involved in his training). Extra funding from the CofE enabled NOS to move to its own city-centre location. There were discussions about planting similar congregations elsewhere, using the movement as a model for youth revival across the church. Trips to California followed as Brain started to scope out a cross-Atlantic expansion. The charismatic young priest even wrote a chapter for Carey’s official book on evangelism.

Then, in 1995, complaints of sexual harassment and assault from female members of NOS were made. As the Diocese of Sheffield finally began to ask more questions of Brain, the married priest admitted he’d had sex with women in his congregation. Shortly afterwards, he resigned from ministry. A damning TV documentary aired around the same time and NOS was shut down for good.

But then, Brain disappeared into obscurity and the CofE swiftly moved on. It took until 2021, after decades of cultural shift and a sea change in church thinking around abuse, for a group of NOS victims to approach the Diocese of Sheffield once again. Some also went to the police, who began an investigation. In 2024, Brain was eventually charged with one count of rape and 33 counts of indecent assault against 13 victims.

‘A CofE sex cult’

The trial saw dozens of witnesses enter the dock, including former NOS members, clergy and even bishops. The jury heard a litany of astonishing evidence about both the culture of the church and Brain’s behaviour. Despite its freewheeling image, NOS was actually run more like a tightly controlled cult, the prosecution said. Members were encouraged to donate large sums of money and cut themselves off from family and friends. Anyone who opposed Brain could be ostracised.

Some observers said they warned the Diocese of Sheffield that things were getting out of hand at NOS, with skimpily-dressed dancers on stage during the rave Eucharists led by Brain drawing particular attention. These whistleblowers found short shrift from then-Bishop of Sheffield, Rt Rev David Lunn, who said he would not conduct a “witch-hunt” against one of the church’s most successful projects.

The trial also revealed a strain of grandiosity within NOS and Brain. At one point large sums were spent by the church to borrow the exact robes worn by Robert De Niro in the iconic film The Mission, so Brain could wear them at his ordination.

NOS was unquestionably unlike anything else in the CofE and, increasingly, not in a good way. A group of Lycra-clad young women known as the Homebase Team were sent to Brain’s house almost daily to wait on him. They massaged Brain while he kissed and groped them. Witnesses said the massages often turned into sexual encounters, despite the priest being married. One alleged she had been “brainwashed” and raped by Brain in the 1980s before he started NOS. As with all the allegations, Brain denied this and said the sex was consensual.

The same alleged victim remained part of NOS until the very end, saying she couldn’t think of any way out and believed Brain to be leading something “of God”. This theme of Brain being a godlike figure of terrifying authority came up again and again.

Another woman told the court she became trapped in an abusive relationship with the priest. Brain would call her to come and “put him to bed” at his home, which often ended in him sexually assaulting her. He would grope her in public and gaslighted her into believing she was a “sex maniac” who needed healing.

She said: “I thought if I questioned it, I wasn’t being a good Christian. I had been controlled – psychologically, spiritually, emotionally. You’re not allowed to question because he represented God.”

Another woman, who joined NOS as a teenager, said it was “basically a CofE-approved sex cult — everything was about sex — the images, the dress code, the black bikinis, the sermons.”

In the 1990s, when the Diocese of Sheffield belatedly woke up to what their golden boy was doing and confronted Brain about sleeping with as many as 20 women in his congregation, he bullishly replied: “It was many more than that, maybe double”.

In court, Brain described himself as “the most radical ordained vicar there was” and said it was “no big deal” that he enjoyed massages that often ended with sexual touching. But while he portrayed this as part of his enlightened, open marriage and postmodern sexual exploration, it was actually a cover for the widespread abuse and exploitation of young women in thrall to him as the God-given leader of their radical Christian community.

Appalling abuses

After weeks of testimony, the jury found Brain guilty of 17 counts of indecent assault. He was acquitted on a further 15 counts of indecent assault, and the jury failed to reach a verdict on a further four counts, and a separate charge of rape.

In response to the verdict, the Bishop of Sheffield, Rt Rev Pete Wilcox, said he was “deeply sorry for the harm” survivors of NOS had suffered, and for the continuing hurt and confusion caused by the “mixed verdict” from Brain’s trial.

“What happened was an appalling abuse of power and leadership that should never have occurred. Where concerns were raised in the past and were not acted upon properly, that was a failing of the church. For those institutional failures I offer an unreserved apology.” He added that an independent review of the church’s safeguarding in the case would begin in the autumn.

The NOS trial comes after a slew of abuse scandals that have battered the national church in recent years, most notably the report into John Smyth last year that forced the then-Archbishop of Canterbury, Most Rev Justin Welby, to resign.

But as well as further damaging the CofE’s reputation, Brain’s conviction also poses questions about its strategy. NOS was, in many ways, a trailblazer and ahead of its time. While it came to an end in the mid-90s and was seen as a failure, the basic idea of reimagining church to appeal to a sceptical, secular younger generation is now core to the church’s approach.

A group of Lycra-clad young women massaged Brain while he kissed and groped them

The stripped back informality and willingness to experiment with traditional worship characterised by NOS is commonplace in a new wave of mostly charismatic evangelical church plants established by the CofE over the past 20 years.

Today’s church has grand plans to start as many as 10,000 new forms of worshipping community, many of them outside the traditional parish system, in an effort to reignite growth following generations of steady decline. Some operate partly outside the usual lines of authority and accountability, as NOS did, and rely more directly on the patronage of individual bishops or parachurch movements.

Therefore, the flaws of NOS exposed by Brain’s trial and conviction will raise questions about the current crop of radical church plants trying to reimagine 21st century worship.

Can we trace any NOS DNA through to today? Do they share any of the weaknesses Brain exploited to coerce and abuse victims, such as an unhealthy deference to charismatic prophetic leaders, or a willingness to jettison good practice and accountability structures in the name of cutting-edge evangelism?

The Brain case may stretch back 30 years, but its final denouement poses a challenge to churches and church leaders up and down the land today.

1 Reader's comment