As the BBC turns 100, Paul Kerensa reviews the religious broadcasting record of the world’s most prestigious media organisation

If you enter Broadcasting House, the BBC’s home for the last 90 years, you’ll see a sculpture of The Sower. Above it, a Latin inscription reads: “This Temple of the Arts and Muses is dedicated to Almighty God by the first Governors of Broadcasting…It is their prayer that good seed sown may bring forth a good harvest.”

When the building opened in 1932, ten years after the BBC was founded, the organisation was radio broadcasting into just under half of Britain’s homes (television was still in development). But 100 years on, do these pillars still stand, or is that inscription now just a museum piece?

Preparing the soil

The British government banned broadcasting when early tests proved too successful: planes couldn’t hear landing instructions while opera singers dominated the airwaves. Wireless communication was for military or other ‘legitimate’ services only – no frivolity.

Radio enthusiasts petitioned for more relaxed rules and the government responded in early 1922.

Peckham preacher Dr James Ebenezer Boon was one such enthusiast; an early adopter who, on Sunday 30 July 1922 placed a radio set on his church altar and left the building. From five miles away in Blackheath, he broadcast his sermon and gramophone hymns to a baffled congregation.

Most had never heard radio before. He reached homes too, greeting them “in the north, south, east and west”. Countless letters were sent in appreciation.

Two months later, the son of a Presbyterian minister arrived in London looking for work. Going straight to a church, John Reith heard the minister read Ezekiel 22:30: “And I sought for a man among them, that should… stand in the gap before me for the land, that I should not destroy it: but I found none” (KJV).

Who would save the nation’s soul from heathen immorality? cried the preacher. Reith was convinced that God wanted him to be that man – he just needed something to lead. Within days, he saw a job advert for general manager of the new British Broadcasting Company.

Once the concept of broadcasting had been explained to him, he realised this was the opportunity he had been looking for. His first task as general manager was to instruct the director of programmes to book a priest for Christmas.

Rev John Mayo gave that first BBC religious broadcast on Christmas Eve 1922: “It is my privilege through the wizardry of Mr Marconi to speak, as I understand, to many thousands of people. Surely no man has ever proclaimed the gospel from such an extraordinary pulpit as I am now occupying.”

The birth of the BBC

To begin with, Reith booked any good preacher he heard, from evangelist Gipsy Smith to army chaplain Woodbine Willie, but they were all recorded in studios. In 1923, the BBC began to broadcast from churches, the first being a performance of Bach’s ‘St Matthew Passion’. But Church authorities were concerned.

The Dean of Westminster banned the broadcast of the Royal wedding of the future George VI that same year, as it may be listened to “in an irreverent manner, and might even be heard by persons in public houses with their hats on”.

Reith needed the establishment on side and eventually won over the Archbishop of Canterbury by demonstrating the potential of radio over dinner. The archbishop was amazed when Reith, disliking the music being played, phoned the BBC to request some Schubert, and the band instantly obeyed.

Church leaders needed to change tune too, though, if Christianity was to reach more listeners. Many ministers thought the broadcasting of religion was vulgar, even blasphemous – and some of these naysayers were guiding BBC policy as part of the Central Religious Advisory Committee (CRAC).

Headed by the Bishop of Southwark, these establishment figures kept an eye on broadcast religion from afar. Soon it became a question of who should be allowed on air, to radiate the right flavour of faith to this new, invisible congregation.

There was much hand-wringing before the bell-ringing, and it took time for a full church service to be broadcast. Protestant or Catholic? Established or nonconformist? Cathedral, church or studio?

Finally, St Martin-in-the-Fields was chosen – a church known for its charity and war work – to appeal to Christians and non-Christians alike. Then in 1924, Rev Dick Sheppard officiated the BBC’s first broadcast service. It was a hit, especially with the housebound and hospitalised, with 8,000 prayer requests reaching the BBC the following week.

Two years later, listener Kathleen Cordeaux began a long campaign for a daily “evensong of the air”. The Daily Service resulted, live from a Savoy Hill studio with roaring log fire. It’s still on today – minus the fire. Post-war, the people of Britain relied on spiritual messages of hope and encouragement.

The Christian establishment still had doubts, though, fearing such broadcasts might stop people going to church!

Dr Ian Robertson’s new book With God on Our Side (New Generation Publishing) tells of various early radio reverends, including the hugely popular WH Elliott, ‘the Radio Chaplain’. As for Sheppard, when he died, 100,000 people queued to pass his coffin lying-in-state. These were the first beloved media ministers.

In 1933, the brilliantly named Rev F Iremonger became the first BBC director of religion. He diplomatically dealt with the CRAC members, who were by now jostling for their own brand of religion on air.

Under his guidance, Christian broadcasting boomed in the 1930s, with more religion than drama in the schedules. Christianity was at the heart of British society, and the BBC reflected that.

As the BBC grew through the 1930s, so did Reith’s dominance. He would interview prospective employees by asking if they believed in Christ’s teachings; he later explained that he was simply asking whether they believed in something.

He ringfenced Sundays as quiet time on air to encourage church attendance. This resulted in two-thirds of listeners tuning in to European stations like Radio Luxembourg instead, which filled Sundays with music and – shock – commercials.

Reith left the BBC in 1938, disappointed that he never achieved his full potential, nor succeeded in his mission. As war returned, listeners relied more than ever on their radios for solace.

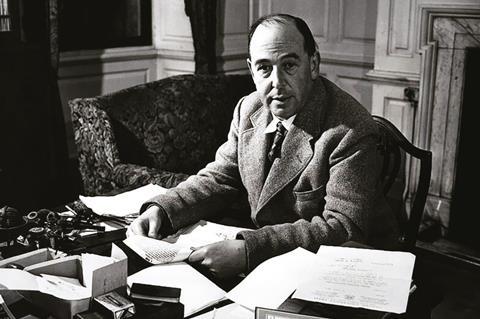

Daily two-minute ‘thoughts for the day’ began in 1939, first called Lift Up Your Hearts. C.S. Lewis’ radio talks inspired a generation, later forming the basis for his acclaimed book, Mere Christianity (Macmillan). Dorothy L Sayers courted controversy as one of the first to update Jesus’ words in her ground-breaking radio play for children, The Man Born to be King.

A changing landscape

Post-war, the first televised church service was on Christmas Day 1949. In fact, television was sold to the world via one religious service: the Queen’s coronation in 1953. Many bought a set just to watch it.

ITV launched in 1955, and within the year it was featuring mini-sermons every Sunday unique to each franchised region. To encourage evening church attendance, both the BBC and ITV were obliged to close completely on Sundays from 6:15-7:25pm, but TV bosses could see that viewers failed to return later.

So ITV led a campaign to overturn the ban, on condition that this early evening slot was full of faith programming.

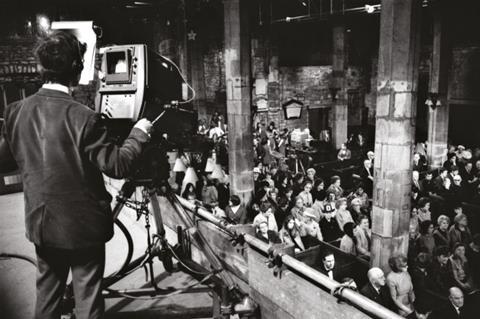

At the BBC, TV executive Donald Baverstock (later to develop Doctor Who, Emmerdale Farm and TV darts) filled this gap with singalong hymns, creating Songs of Praise in 1961. By removing the sermons, it became potentially more inclusive – Words of Praise might have excluded some denominations.

Britain’s spiritual landscape was starting to shift, but the BBC held firm with its daily radio ‘thoughts’. The Home Service had Ten to Eight at ten to eight; The Light Programme had Five to Ten at (you guessed it) five to ten. From 1970, the former became Radio 4’s Thought for the Day, the latter Radio 2’s Pause for Thought, both still on air today.

Week one’s Pause for Thought guests were unnamed – ‘a doctor’, ‘a dustman’ and so on. Week two included celebrities; the seventh ever was a certain tracksuited DJ who spoke on the topic of good manners.

To reflect changing Britain in the 1970s, the Annan Committee on the Future of Broadcasting requested more diverse output. Programming became less religious, more ‘religious discussion’. Remaining services widened their Anglo-Catholic focus, featuring more Black, evangelical and minority churches.

A major change came in 1990, as Margaret Thatcher passed the Broadcasting Act. Proselytising was banned and ITV’s ‘God slot’ vanished. Commercial radio began to bloom instead, with specific Christian programming via Premier Christian Radio and UCB possible from the mid-90s onwards.

At the BBC, Religion and Ethics moved to Manchester in 1994. Today’s output includes documentaries (Pilgrimage, The Monastery) and discussions (Sunday Morning Live). Other faiths enjoy greater representation – such as BBC Three’s Make Me a Muslim and the Asian Network.

But programming on any faith is now rather rare. Unlike in the 1930s, drama has overtaken religion in the schedules.

The world’s first religious broadcast

The world’s first entertainment broadcast was a religious one. On Christmas Eve 1906, Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden gave a short transmission for ships near Massachusetts: a violin rendition of ‘O holy night’ and a reading from Luke 2: “Glory to God in the highest; and on earth peace to men of good will” (DRA).

This one-man broadcast station – engineer, producer, presenter – is a reminder that while organisations get the headlines, religious broadcasting’s history is populated by creative individuals, looking forwards and upwards.

A new season

Half the planet recently gathered to watch the state funeral of Elizabeth II. But one CNN headline suggested this was the death-knell of the medium – “the end of television”. We’ll never watch one event, together, in quite the same numbers.

It’s true the Queen has brought huge viewing figures to Christian services. Her coronation helped launch television to 277 million viewers in 1953; 1 billion watched her grandson William marry Catherine; this autumn 4.4 billion tuned in to bid her farewell.

Thanks to broadcasting, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s sermon is the most listened to of all time.

But without the figurehead of the Queen, and left to our own devices, our viewing and listening may become more compartmentalised in the coming decades (think Netflix, Spotify and others). The government has told the BBC that this licence fee deal is its last.

With a potentially different funding model for public service broadcasting, how will religious broadcasting adapt?

The growth of the internet has shrunk the world, with podcasting and livestreaming opportunities making us all potential broadcasters. A century ago, the church of our first religious broadcaster Dr Boon had its minister absent but congregation present.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the opposite occurred as preachers became YouTubers: minister present, congregation absent.

Religious broadcasting serves a different purpose than it used to. The early BBC – one channel, one audience – ministered to the nation, even the empire. Now we have choice, and those seeking Christian programmes are likely to already be Christians. The media either preaches to the converted, or doesn’t preach at all.

The BBC’s new religion editor, Aleem Maqbool, is optimistic that religious stories are finding a place in news coverage. After all, they’re human stories, of faith and hope amid global crises. But with enforced quotas for religious programming all but gone, we may need to remind commissioners, and viewers, that religious stories are still worth telling.

If you watch a religious programme and enjoy it, make sure you talk about it with friends and on social media. Ask for more – and you may receive. But expect the long haul: Kathleen Cordeaux’s 1926 campaign took two years before the Daily Service arrived.

The government is keen to update public service broadcasting for the streaming age – which may mean cuts, closures and major changes to schedules. Old favourites may be uprooted; new favourites may need time to germinate. Programme-makers may ponder what religious programming looks like on Netflix.

The transmission of religious services may have a rocky path ahead, but daily scatterings of inspiration continue as we pause for Thought for the Day. Some like it, some loathe it, but this welcome deep breath away from the news will continue if listeners want it.

Self-improvement podcasts and YouTube channels imply that we still seek answers to life’s questions; carefully presented religious media can still offer a way, truth and life.

Whatever the next century holds, it’ll be down to creative, faithful individuals to bring the immortal through the invisible, into our homes, eyes and ears. We may not gather around the television by the billions again, but we still crave spiritual sustenance.

And whether it’s by TV, tablet or earphone, I pray we’ll keep following the example of the parabolic sower: broadly casting our message, hoping it finds good soil to produce a crop 100 times what’s sown.

Whoever has ears, let them keep on hearing – even if the seeds are now in new hands.

No comments yet