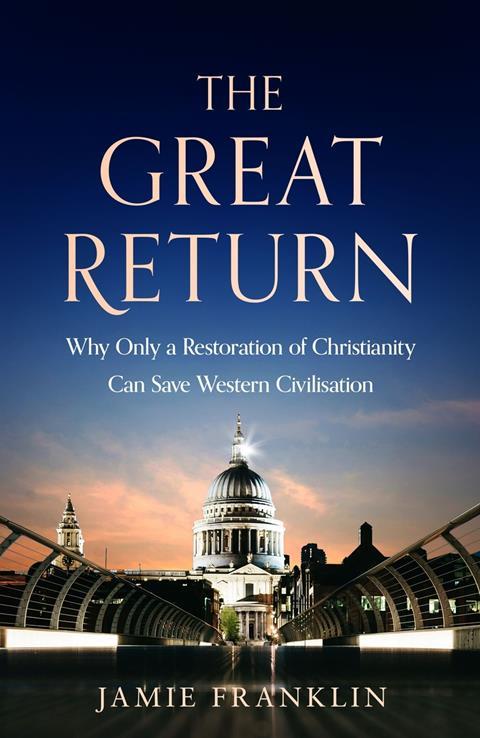

Jamie Franklin’s The Great Return urges the Church to reclaim its past dominance but confuses the decline of Christendom with that of Christianity, argues Dr Joshua Bloor. True renewal, he argues, must centre on Christ, not nostalgia

In The Great Return (Hodder Faith), Jamie Franklin presents a stark and dystopian vision of Christianity’s current condition, warning that unless the Church returns to its former glory, society is destined to spiral into moral chaos.

It is a provocative call for the Church, particularly in the West, to come back from the edge of spiritual exile and reclaim its theological, liturgical, and moral convictions. Written in the shadow of the pandemic and its ecclesial aftermath, the book is part lament, part warning, and part rallying cry. Franklin believes Covid-19 exposed a deeper rot within the modern Church: not merely temporary confusion, but a longstanding abandonment of Christian orthodoxy, reverent worship, and prophetic clarity.

Yet at the core of Franklin’s argument lies a fundamental flaw: he appears to conflate the decline of Christendom (a political and cultural expression of Christianity) with the decline of Christianity itself. The reality is quite the opposite. There are more Christians alive today than at any other point in history. In 1910, often viewed as the height of Christianity’s institutional power, there were approximately 600 million Christians. Today, that number is around 2.38 billion.

Take global Pentecostalism, for instance. Anthropologists and scholars of religion have been astonished by its explosive growth throughout the 20th century, particularly in light of its rise during an era dominated by secularism and increasing religious pluralism. Estimates suggest that there are now between 600–750 million Pentecostals worldwide. While Franklin’s focus is primarily on the West, to overlook the extraordinary vitality of the global Church is to ignore the dynamic, spirit-empowered reality of Christianity today.

In this light, the decline of Christendom cannot be equated with the decline of Christianity. “Restoring Christianity” cannot simply mean recovering cultural dominance or returning to a state-sponsored version of the faith. Is cultural influence really the same as faithfulness? Is a return to a Christianised public square truly the kind of renewal the Church needs? Franklin could have benefited from drawing a sharper distinction between cultural Christianity and biblical Christianity, where Christ, not heritage, nostalgia, or political power, is the living Lord at the centre of the Church’s life. True restoration is not a return to an idealised Christian past, but a radical reorientation toward Christ himself.

While Franklin mourns the loss of the Christianised West, we should also ask: what might God be doing in the dismantling of Western Christian hegemony?

The Church doesn’t need to reclaim its past cultural dominance. It needs to recover its true identity

A further concern is Franklin’s nostalgic and somewhat romanticised view of Christian history. Christianity’s past is not simply glorious, it is also deeply compromised. From the earliest New Testament letters, the Church has struggled with sin, division, and spiritual failure. Post-Constantinian Christendom brought simony, clerical abuses, and political manipulation, as seen in the Avignon papacy and the Great Schism. The Reformers themselves emerged precisely because of these entrenched corruptions.

Franklin writes: “We do not live at the zenith of moral development but on the other side of the Christian revolution which bequeathed to the world a vision of humankind as made in the image of God and destined for transcendent glory. The vision brought about belief in a moral universe that was reflected in the great cultural, artistic and architectural achievements of medieval Europe. We warm ourselves now on the dying embers of that revolution…”

While rhetorically powerful, this view idealises a medieval Christianity whose cultural achievements were not solely, or even primarily, Christian. In fact, much medieval art and architecture was later critiqued as stagnant and excessive, fuelling the Renaissance, not as a return to Christian greatness, but to the ideals of the ancient Greco-Roman world.

None of this is to say that Franklin’s warnings are without value. His calls for confidence in scripture, reverent worship, and Christian courage are well placed. The Western Church undoubtedly faces a crisis of conviction. In diagnosing the superficiality and cultural accommodation of many contemporary expressions of Christianity, Franklin offers a bracing and needed critique. His prose is passionate, combative, and earnest, often refreshingly direct in a climate of theological vagueness.

But perhaps what the Church needs most is not to reclaim its past cultural dominance, but to recover its identity as a spirit-filled, Christ-centred, cross-shaped people. The “Great Return” must not be to a lost golden age or cultural construct, but to Jesus himself: crucified, risen, reigning, and present by his spirit in diverse communities around the world.

The Great Return by Jamie Franklin is out now

For more from Jamie Franklin listen to our interview with him on The Profile podcast

No comments yet