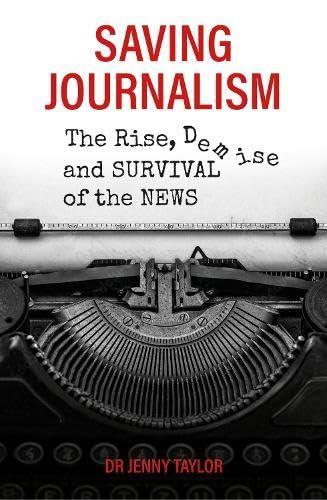

In her bold and timely book, Dr Jenny Taylor explores how faith shaped the birth of modern news, and why reconnecting with those roots might be key to its survival

In a world of fake news and disinformation, trusted journalism is fighting to survive.

While obscure algorithms and clickbait dictate what many people see in their newsfeeds, professional journalists are losing their jobs and truth is becoming a casualty of the relentless battle for people’s fleeting attention.

It’s into this crisis that journalist and cultural analyst Dr Jenny Taylor steps, offering a bold and timely intervention. In Saving Journalism: The Rise, Demise and Survival of the News (Pippa Rann Books), she traces the biblical and religious roots of journalism, examines why the news media is in such steep decline, and outlines an action plan to help it survive and thrive.

Shining a light into today’s bleak media landscape, Taylor urges journalists to reconnect with their profession’s rich, justice-driven heritage. She traces this lineage through the bold voices of Old Testament prophets, the Reformation’s push for literacy so people could read scripture for themselves, and the Christian convictions of pioneering editors who were even willing to face prison for exposing wrongdoing.

The roots of journalism are deeply entwined with faith

Yet today, many journalists lack personal experience of belief and often operate from a default secular perspective. This can lead to blind spots - missing key dimensions of major stories, or failing to cover them altogether.

These Christian roots, Taylor argues, have largely been forgotten. The widespread secularisation of the media has left it without firm foundations - adrift, and unsure of its purpose. Against this backdrop, public interest journalism is left vulnerable, with little defence against the economic and political forces stacked against it.

Taylor’s analysis echoes recent research showing that mainstream media often struggles to report on public expressions of Christian faith — particularly when voiced by athletes or celebrities. Similarly, the persecution of Christians overseas tends to be under-reported or overlooked entirely.

Structurally, the book is divided into three parts. Taylor describes the first as: “a dive into the murky waters of the present day – the corruption of the press without an overt moral compass, the lazy reportage, the news deserts, and the plagiaristic resort to robotic news cycling.”

The second section explores the heritage of the modern news business. It highlights “religious dissenters, working against massive cultural pressures that cost their lives and livelihoods - dissenters who still hold up a mirror to our own apathetic quest for truth worth telling.”

In the final part, Taylor sets out a series of action points aimed at helping the media unscramble: “the confused matrix of ideas in which journalism happens today.” These include encouraging reporters to understand their own heritage, become familiar with the Bible and other scriptures, and urging churches to advocate for greater religious literacy and raise awareness of journalism’s religious roots.

Taylor writes from a wealth of experience in and alongside the media, across a range of contexts and locations – including Northern Uganda, where in the early 2000s a brutal war had been raging for 17 years, largely unnoticed by the outside world. International news outlets were hesitant to cover the conflict due to its strong religious dimensions. But through first-hand reporting and by bringing a local bishop to London, Taylor helped raise awareness and played a key role in getting UK and international agencies to focus on the conflict.

“It was,” says Taylor, “religiously literate journalism that made the difference – public interest journalism that took seriously the spirituality of the people.”

This is a well-researched and fascinating read – praised by historian and author Tom Holland as: “a brilliant and unexpected study of how journalism came to be the ‘enfant terrible’ of the modern world, and what it would mean to lose it.”

It’s a particularly valuable resource for any Christian considering a career in the media, offering a deeper understanding of journalism’s biblical roots – from speaking truth to power and giving voice to the voiceless, to exposing wrongdoing with integrity.

Journalists who exposed the Post Office scandal, grooming gangs, and government leaks about Afghans who had worked with British forces, have performed a public service – as have those who have revealed abuse scandals within church organisations. Journalism is a worthy calling for any Christian, and Taylor’s analysis offers strong support for this view.

Organisations such as Christians in Media and St Bride’s Church on Fleet Street show how churches and the media can work in partnership. Taylor’s book is a valuable contribution to ongoing conversations about the future of journalism. Increasing religious literacy among journalists and media outlets could strengthen the credibility of their reporting – especially in a world where religion continues to play a major role, often far more than many journalists appreciate.

1 Reader's comment