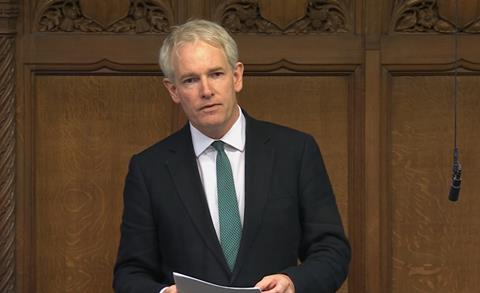

Danny Kruger MP’s impassioned speech to an empty House of Commons chamber on the need to restore the UK’s Christian heritage has been viewed more than 3 millions times. It’s a roadmap for a Christian counter-revolution, says David Campanale

Later this year, events will be held in Kingston upon Thames to mark the 1100th anniversary of the coronation of Anglo-Saxon King Athelstan, on 4 September 925AD. Grandson of King Alfred the Great, Athelstan can claim to be the first King of all Britain.

Anglo-Saxon scholar, Professor Michael Wood, marks this date for its significance in the Orthodox calendar: it is “the feast of Moses the Lawgiver: a very important figure in the eyes of Alfred and Althelstan who had a vision of England as a Christian kingdom under a version of Mosaic Law.”

Not just a “vision” and more of a covenantal reality, the royal line of Christian Anglo-Saxon kings crowned in Kingston was decided by means of oaths to embrace the pattern of the “blessings and curses”, illustrated in Leviticus 26 and set out in the ‘Covenant Code’ of Exodus 21:1 – 22:16. Alfred and Athelstan acted to bring their nascent kingdom into the promises of God, extended by means of the New Covenant, from Israel to all nations.

Addressing our current moment, Conservative MP Danny Kruger has issued a powerful challenge – albeit in an empty Commons chamber about to rise for the summer – that Britain should grasp how the nation is bound by Alfred’s ancient Covenant.

As Kruger put it, “Uniquely among the nations of the world, this nation—England, from which the United Kingdom grew—was founded and created consciously on the basis of the Bible and the story of the Hebrew people. In that sense, England is the oldest Christian country and the prototype of nations across the West.”

I gave a speech today in an empty chamber. It’s about the need for a Christian restoration. pic.twitter.com/QkphdhUDvF

— Danny Kruger (@danny__kruger) July 17, 2025

Kruger is not unique in taking the idea of covenant seriously. Popular US messianic writer and pastor, Jonathan Cahn, regularly features in the New York Times best seller lists and makes the claim that America too is “covenanted” to God. In his book, The Return of the Gods, Cahn says that America has entered into a phase of redemptive discipline, as turning away from Christ has caused ancient gods to remerge. Cahn says the god Baal – which means, ‘Master’, or ‘Possessor’ intends to command and take possession of the whole house of Western Christian civilisation, filling room by room all the places swept clean of Christianity.

England was founded on the basis of the Bible. In that sense, England is the oldest Christian country

The idea of spiritual warfare reflected in the dynamics of law-making in Westminster is touched upon briefly by Kruger in his book, Covenant: The New Politics of Home, Neighbourhood and Nation. He writes, “The culture war…is a religious conflict about the right gods to worship. As such, it is more than a series of skirmishes for the tokens of identity, for flags and statues and the history curriculum. It is a battle for the strongholds of society itself.”

Kruger develops his “strongholds” theme powerfully in his Commons’ speech. He says the impact of “one thousand years” of the Christian common law tradition – is the demand “that power should arrange itself for the benefit of all the people under it, and specifically for the poorest and weakest”.

“In the absence of the Christian God”, he continues, “we do not have pluralism and tolerance, with everyone being nice to each other in a godless world”. Instead, he says, we have “catastrophes of social breakdown, social injustice, loneliness and emptiness on a chronic scale”. He says that “in abandoning one religion we simply create a space for others to move into.” He identifies “a combination of ancient paganism, Christian heresies and the cult of modernism”.

Perhaps most notably, Kruger took aim at the votes of MPs to decriminalise abortion and legalise assisted suicide. He said they had authorised “the killing of unborn children, of nine-month old babies” and to “allow the killing of the elderly and disabled,” describing these votes as “a great sin.”

“The fact is that the strong gods are back”, Kruger proclaims, “and we have to choose which god to worship. I suggest we worship the God who came in the weakest form, Jesus Christ. This God is a jealous god—it is him or nothing—and we have to own our Christian story, or repudiate it.”

Kruger insists that secularist religion “must simply be destroyed, at least as a public doctrine. It must be banished from public life—from schools and universities, and from businesses and public services.”

Outlining what looks like a programme for a Christian counter-revolution, Kruger alludes to the cycles of loving discipline implicit in this covenantal paradigm: “a wind is blowing, a storm is coming and when it hits we are going to learn if our house is built on rock or on sand.”

Kruger calls for a “restoration” and “a revival of the faith” and calls it a “mission for the whole country”. But his roadmap could be a little clearer. He says the “Puritans in the seventeenth century”, among others, “brought Britain “back from the edge”. John Milton may therefore serve as a prompt, citing as he did the godly reforming zeal of King Josiah.

2 Kings 23:3 has the paradigm, referring to how “all the people from the least to the greatest” came to hear read “all the words of the Book of the Covenant, which had been found in the temple of the Lord.” It says Josiah “stood by the pillar and renewed the covenant in the presence of the Lord to follow the Lord and keep his commands”. And adds, “Then all the people pledged themselves to the covenant.”

Could such a gathering across our nation (perhaps during the upcoming National Week of Prayer), invoke the terms of the Covenant and lead to the move of restoration that Kruger seeks?

4 Readers' comments