Justin Brierley explores the surprising rebirth of belief in God

I knew something had changed when, in 2018, I received an unexpected email from atheist thinker Peter Boghossian. I couldn’t quite believe what I was reading.

At the time, Boghossian was a professor of philosophy at Portland State University. When he joined me for a podcast debate on faith in 2014, he had been as anti-religious as they come. His book A Manual For Creating Atheists (Pitchstone Publishing) was a set of strategies for talking religious people out of their beliefs, which he claimed were akin to a mental delusion.

However, four years later, when Boghossian responded to an invitation to a fresh dialogue, he told me that he was no longer participating in debates against Christians. Indeed, he now felt quite differently about people of faith: “You might be surprised at how much I have in common with you now”, he wrote. His focus had shifted to countering a far more pernicious threat, he continued, of which I would find out more soon.

What had led to this dramatic change of tone? A few months later, it became clear.

Boghossian, along with two of his academic colleagues, were at the centre of a ruse, submitting hoax academic papers to peer-reviewed journals, in order to expose so-called ‘grievance studies’ – critical theories in academia that placed gender, sexual identity and race at the centre of every subject. Using politically correct-sounding terminology they were able to pass off outlandish theories about dogs engaging in rape culture, and dressed-up sections of Mein Kampf as genuine academic arguments.

The hoax was eventually rumbled, but the episode sparked a significant debate. Boghossian and his colleagues claimed their spoof papers showed how certain orthodoxies and ideologies were taking over university campuses and squashing academic freedom by cancelling those who disagreed with them.

Whatever you think of the hoax, what struck me most was that Boghossian now saw Christians as allies in this fight. He was still an atheist, but his tone had changed dramatically. Christians were no longer the enemy…that was now the progressive left.

Boghossian’s change of heart is one among many stories. The culture wars have shifted the ground in the dialogue between Christianity and atheism in recent years.

NEW ATHEISM

I began hosting the faith discussion show Unbelievable? on Premier Christian Radio in the mid-2000s just as New Atheism was gathering steam. It was a movement that saw several high-profile figures spearhead a newly hostile approach to religion. The bestselling books of the ‘four horsemen’ – Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett and Christopher Hitchens – painted faith as ignorant and dangerous. The 2009 atheist bus campaign proudly declared: “There’s probably no god. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life”, and a sprawling online community gathered for regular atheist conferences and rallies.

The conversations I hosted in those years were primarily combative debates between ardent atheists and Christian thinkers, which matched the boisterous and dismissive attitude of New Atheism in general.

But, as the years progressed, the conversations changed and the atheists and agnostics who appeared on the show were keen to distinguish themselves from New Atheism. “I’m not a Richard Dawkins type of atheist” became a common refrain. Guests increasingly seemed to share more common ground on cultural and social issues, even if they didn’t share the same faith.

The culture wars have shifted the ground in the dialogue between Christianity and atheism

I sensed that the public were becoming tired of the shrill dogmatism of the New Atheists. Richard Dawkins, once a renowned biologist, had become an angry zealot. Meanwhile, the New Atheist movement itself began to experience an internal meltdown.

Some were unhappy that a phalanx of old white men was leading it. They said there was too much sexism, patriarchy and privilege. A splinter movement called ‘Atheism+’ called for the embrace of LGBT rights, feminism and social justice issues. But others reacted strongly against politically correct ideologies overtaking the movement.

The controversies multiplied. Many of the chief voices in the movement fell out with each other, resulting in atheist conferences being cancelled as speakers refused to share a stage. In 2021, Dawkins himself was stripped of his ‘Humanist of the Year’ award by the American Humanist Association for critiquing transgender ideology (something the biologist has doubled down on in recent months).

It seemed that once the New Atheists had agreed that God didn’t exist and religion was bad for you, they couldn’t agree on anything else.

NEW RELIGIONS

Having torn down the notion of God, New Atheism offered very little with which to replace it. Science and reason alone won’t buy you meaning, purpose and value. Apart from its internal squabbles, the real reason that New Atheism stalled as a cultural movement was that it failed to give people a story to live their life by, so people went looking for a story elsewhere.

To question someone’s personal identity is regarded as an act of sacrilege

In our contemporary culture, we see this most clearly in the numerous ideologies around LGBT, gender and race that have proliferated in recent years. Many people live their lives through these stories. There is no doubt that a strong sense of justice motivates such causes, but they often take on a quasi-religious significance too. To question someone’s personal identity is regarded as an act of sacrilege. Social activism has a very religious feeling, with its own sacred texts, rituals and symbols (think of the pride flag), and its heretics too (think of JK Rowling). And it’s not just the progressive left. You’ll see the same quasi-religious sentiment in conservative nationalism and right-wing conspiracy theories too.

I don’t think we should be surprised that these new forms of religions have arisen. GK Chesterton is cited as saying that when people stop believing in God they don’t believe in nothing, they become capable of believing in anything. To put it another way: People don’t stop being religious when they lose the Christian story, they just become religious about different things.

We are meaning-seeking creatures. We need a story to live by. And when the Christian story – which for centuries gave individuals and whole cultures a sense of purpose and direction – goes away, people will find something else to fill the gap.

The problem is that these new identities, stories and quasi-religious ideologies are often at odds with each other, as evidenced by the polarised social media battles that fill our timelines. Those who led New Atheism are no longer talking about religion. Instead, their leaders have taken sides in the culture wars. Boghossian now finds himself among the ‘anti-woke’, fighting new forms of religion that he believes are a greater threat to science and reason than the Bible ever was.

NEW THINKERS

As New Atheism faded from view, it left behind a lot of secular people still looking for intelligent answers to life’s deepest questions. Indeed, the rise of social media and the culture wars has also hastened the emergence of a ‘meaning crisis’ in today’s generation. Despite our material comforts and technological advantages, anxiety, depression and mental–health problems are at an all-time high, especially among the younger generation. People are desperate for a better story to live by.

As the conversations on Unbelievable? turned towards these new social trends, I noticed that a new generation of secular thinkers were emerging, picking up the baton that the New Atheists dropped. But this time they were willing to acknowledge the power and influence of the Christian story as a way of accessing meaning and purpose. God was back in play.

The most obvious example of this phenomenon was when Canadian psychology professor Jordan Peterson shot to fame in 2018, following the publication of his bestselling book 12 Rules for Life (Random House). Peterson filled whole arenas with young men who hung on his every word as he dispensed wisdom on how to live a meaningful life, frequently invoking lessons from the Bible along the way. Peterson’s politically incorrect opinions often generate controversy, but he has continued to vigorously promote the value of Judeo-Christian wisdom on his popular podcasts and videos. Indeed, he insists that the origin story in Genesis, in which men and women are created in the image of God, is the only story that has ever grounded our belief in human dignity and value.

People are desperate for a better story to live by

Peterson was not alone. I noticed more and more intellectuals critiquing the once-popular New Atheist movement and, often, offering answers that were sympathetic to Christian faith.

Historian and podcast host Tom Holland, author of the bestselling book Dominion: How the Christian revolution remade the world (Basic Books) has been reminding secular humanists why their beliefs in human rights, freedom and sacrifice were handed to them by the followers of Jesus, not enlightenment scientists.

Female campaigner Louise Perry, author of The Case Against the Sexual Revolution (Polity), has been pointing out that monogamous Christian marriage has turned out to be the most reliable way of ensuring positive family outcomes.

Popular science communicator Paul Davies has been researching the serendipitous nature of our universe that has allowed conscious human life to develop within it. Contra the atheist view that life is a cosmic accident, he has been showing why a life principle (a Logos, to use the Greek word) seems to be at work in nature.

There’s also the renowned psychiatrist and neuroscientist Iain McGilchrist, whose influential books such as The Master and His Emissary (Yale University Press) show how our brains are wired to be religious and why a divine mind is required as a foundation for consciousness.

The list goes on. It’s noteworthy that none of the people above are conventionally religious. Their conclusions are wrought from secular research and reflection, not a pre-commitment to Christianity. Yet these are now the voices that intellectual seekers are turning towards to make sense of life. It has become respectable to take the Christian story seriously again.

5 secular thinkers encouraging people to take faith seriously again

The Canadian psychologist initially rose to prominence for his political stance against transgender ideology. His lectures on the psychological significance of biblical stories have been viewed millions of times on YouTube and helped win him a legion of fans who value his life advice.

After working in a rape crisis centre, journalist and female violence campaigner Louise Perry says she lost her faith in liberal feminism. Her subsequent book The Case Against the Sexual Revolution (Polity) comes to surprisingly Christian conclusions about sex and marriage.

Jonathan Haidt

The secular Jewish psychologist is the author of bestselling books including The Righteous Mind (Penguin). Unlike his New Atheist contemporaries, Haidt has repeatedly championed the benefits of belonging to religious communities and the well of wisdom contained in scriptural texts.

Bari Weiss

After resigning her position at The New York Times in protest at the curtailment of free thought within journalism, Weiss has gone on to re-embrace a traditional Jewish identity. She says that New Atheism laid the ground for the rise of quasi-religious ‘woke’ identities. She now runs a popular independent media outlet The Free Press.

Holland is a bestselling popular historian whose podcast ‘The Rest is History’ reaches millions of people globally. His book Dominion (Basic Books) charts how Christianity uniquely gave the world its beliefs in human dignity, equality and freedom. His research into the Greco-Roman world convinced him that, even as a secular Westerner, he was “in almost every way, a Christian”.

A NEW WAVE OF FAITH?

Daniel James described himself as a “hardened anarchist atheist” in his late teens, but was recently baptised in the Catholic Church. James says that, as a young man, he thought the Bible was a “silly book,” taking his cues from the New Atheist’s description of the Bible as the work of “ignorant Bronze Age peasants”. However, when he started watching lectures by Jordan Peterson he found himself “blown away”.

“I’d never heard the Bible spoken about in that way…Jordan really just opened the door for me to understand that, yes, it was written by people who lived in an era before science, but they were by no means ignorant.”

I have heard many similar stories of people finding that these new thinkers are a gateway to Christianity. These can be set alongside a variety of well-known voices who have begun to take God seriously again.

Rock musician Nick Cave’s recent memoir Faith, Hope and Carnage (Canongate Books) describes his own pathway towards God through personal tragedy while the celebrated poet and author Paul Kingsnorth recently announced his conversion to Christianity after decades of dabbling with atheism, Buddhism and Wicca.

Naturally, these individual stories, while encouraging, don’t necessarily mean that a Christian revival is just around the corner. The latest surveys still show a picture of terminal decline in many parts of the Church and the continuing rise of those who describe themselves as ‘nones’ (no religious affiliation). However, it’s also apparent that New Atheism failed to make many converts to scientific materialism, and that the ‘nones’ continue to encompass many ‘spiritual-but-not-religious’ types who are looking for a meaningful story to be part of.

It has become respectable to take the Christian story seriously again

The atheist view of reality has worn threadbare and the postmodern stories that our culture is telling itself are likewise running out of steam. These are the conditions under which I believe the tide could be turning, and the Christian story could come rushing back in.

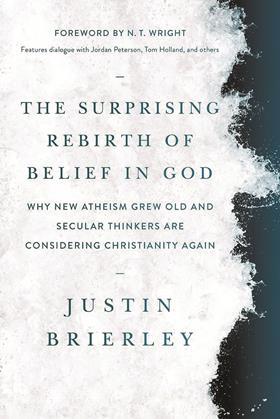

My book The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God (Tyndale House) uses the “sea of faith” as its central metaphor. The term was coined by the Victorian poet Matthew Arnold, whose poem ‘Dover Beach’ speaks of the “melancholy, long, withdrawing roar” of “The Sea of Faith” in his generation.

A few years ago I hosted a conversation with Douglas Murray, the well-known cultural commentator and associate editor of The Spectator. Murray (who calls himself a “Christian atheist”) is another secular thinker keenly aware of both the failure of New Atheism and the immense cultural heritage that Christendom has gifted the world. During our conversation he mentioned that several of his friends had recently converted to Christianity.

Referencing Arnold’s poem, Murray speculated that this may be a time in which the Church is once again able to speak to “a more receptive crowd”. “The interesting thing about the sea of faith is there’s no reason why it can’t come back in again,” he said. “That’s the point of tides.”

Perhaps we are indeed seeing a turning of the tide. But will the Church be ready to receive the refugees of the ‘meaning crisis’ washed up on its shore? I pray that it will.

Talk about your faith with confidence. Visit premierunbelievable.com for apologetics resources and conversations that matter

Justin’s latest book The Surprising Rebirth of Belief in God (Tyndale) is available now

5 Readers' comments