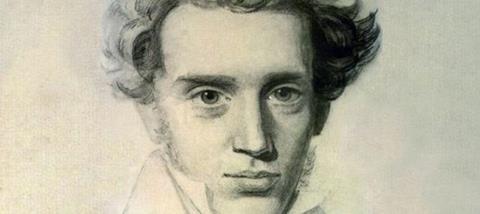

Søren Kierkegaard was born in Denmark in 1813 and became a famous philosopher, as well as a critic, poet and theologian. Massively influential, he is credited with being the first “existentialist” (another great word to use if you want to sound clever) and for using stories and extended metaphors to explain or illustrate his ideas. These are very similar to Jesus’ parables and many have a sting in the tail and still pack a punch today. We’ll have a look at some of them later.

But first of all, don’t be put off by the name “Kierkegaard”. It sounds difficult but give it a go, roll it round your mouth until it trips off your tongue. You’ll be glad you did, it’s a terrible impressive name to drop into conversations and is guaranteed to make you sound brainy. If merely using his name makes you sound clever, then actually quoting Kierkegaard will have people thinking your are downright intelligent. If you are feeling really brave you could try his first name, too: Søren (although I’ll excuse you his middle name – Aabye – as no-one uses it.)

Before that, some biography. Kierkgaard’s life was not a long or happy one. Born into a respectable middle-class family, he had an odd and difficult relationship with his father, from whom it seems he inherited a negative and somewhat gloomy disposition. In fact, it’s likely that Kierkegaard had what we would now call clinical depression, in which guilt and anxiety featured strongly. But Kierkegaard also inherited his father’s sharp mind, ready wit, an occasionally sarcastic sense of humour and a strong Christian faith. As well as a troubled relationship with his father, Kierkegaard had a difficult relationship with women in general and with one woman in particular: his fiancée Regine Olsen. Tragically, it seems that the reason Kierkgaard broke-off their engagement was that he felt his “melancholic temperament” made him unsuitable for marriage and poor husband material. So Kierkgaard’s life was a case study in what he would call “existential angst”.

With this background, it is perhaps unsurprising that much of Kierkegaard’s work is negative and critical – especially of the established state church. Adopting many pseudonyms, he wrote scathing attacks on the luke-warm, half-hearted Christianity that he saw in Denmark at that time: “Present-day Christendom really lives as if the situation were as follows: Christ is the great hero and benefactor who has once and for all secured salvation for us; now we must merely be happy and delighted with the innocent goods of earthly life and leave the rest to Him. But Christ is essentially the exemplar, that is we are to resemble Him, not mere profit from Him.”

Using pen names gave Kierkegaard the freedom to speak out prophetically and he was widely published – and made a few enemies. But God’s grace and mercy and forgiveness are also major themes in his works and perhaps his best-known prayer is: “Father in Heaven! Do not hold our sins up against us but hold us up against our sins, so that we wouldn’t be reminded of what we have committed against you but would remember what you have forgiven us of; not of how we went astray, but of how You have saved us!”

Another main theme is the desire for existential authenticity. For Kierkegaard, being authentic means having an authentic faith and an authentic relationship with God. He said: “There are many people who reach their conclusions about life like schoolboys; they cheat their Master by copying the answer out of a book without having worked out the sum for themselves.” He also had a keen eye for contradictions and inconsistencies, often seeing the ironies and playfully toying with them: “The Bible is very easy to understand. But we Christians are a bunch of scheming swindlers. We pretend to be unable to understand it because we know very well that the minute we understand, we are obliged to act accordingly.” Ouch.

Let’s end with a few more words from the man:

- “God created everything out of nothing. Wonderful, you say. Yes, to be sure, but He does something even more wonderful: He makes saints out of sinners.”

- “Christ has not only spoken to us by his life but has also spoken for us by his death.”

- “It so happened that a fire broke out backstage in a theatre. The clown came out to inform the public. The audience thought it was just a jest and applauded. He repeated his warning, they shouted even louder. Thus I think the world will come to an end amid general applause from all the wits, who believe that it is a joke.”

Kierkegaard’s own life came to an end in Copenhagen on the 11 November 1855. He was 42.

The best introduction to Kierkegaard’s work is Provocations: Spiritual Writings By Søren Kierkegaard edited by Charles E. Moore (Plough). If you want to be challenged rather than comforted this is a good place to start.

Rev Oliver Harrison is vicar at Holy Trinity Wilnecote