From Desmond Tutu to Scarlett Johansson, interviewer of the year, Cole Moreton, has met the great and the good. He reveals what the extraordinary encounters have taught him about the divine spark that is present in all of us

Who is the most remarkable person you’ve ever met? It could be your mum, or a mate who stood by you, a stranger on a train or a have-a-go hero. Anyone, really. I’d like you to think about that as I share some of the things I’ve learned from working as an interviewer, because although I have met the famous and the infamous, the scandalous and the adored, I have also discovered that some of the bravest, most creative, compelling and fascinating people on this planet are the ones known only to their friends and to God.

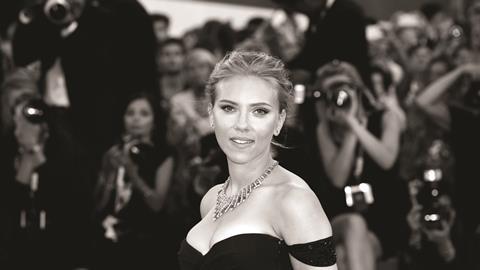

Let’s start in a dimly lit bar at the plush and expensive Carlyle hotel on New York’s Upper East Side. This is the setting for the first of the 18 tales in my new book, Everything is Extraordinary: True stories about how we live, love and pay attention (Hodder & Stoughton). It is 2017 and I am there to meet a young woman whose image I have just seen on a billboard 100ft high in Times Square. I hear a voice: “Hey, how ya doing?”

Heads turn at the unmistakable, smoky tones of Scarlett Johansson, the biggest female box office star in movie history, as she shrugs off an ordinary green parka. Johansson is otherwise dressed entirely in black, except for Pollock-style paint splatterings on her Doc Martens. “I can scurry around the streets like any other city rat,” she says and laughs lightly. We talk about her new movie and what it’s like to be an Avenger. Time slips by quickly as she moves on to her twin brother, Hunter. “I’m just realising that I’ve always had this other half out there. Being a twin affects all your life. I notice in my intimate relationships, I’ve chosen people as a result of not wanting to feel alone.”

I should pick up on that, but I don’t, because I’m stunned by what’s happening here. Fifteen minutes is all you normally get with Hollywood stars, but we’ve been talking for more than an hour now and there is not a PR in sight. A vain part of my brain starts chattering like a chimp: “We’re getting on well. This is great. Almost like a date…”

Yes, I do know how deluded that sounds. Johansson is widely seen as one of the most attractive people on the planet and frankly, I am not. I turn to my notes in an effort to shut up the chimp, but unfortunately the next question is one I have promised to ask for my teenage daughter: “What is it like when you know everybody fancies you?” She laughs again: “Ha! Nice. Yeah, that definitely sounds like a question from a 15-year-old!”

Johansson says she feels like a normal person, with all the usual insecurities. “For as many people I meet who fancy me – that’s a very English way of saying it – there is another half who just think: Who does this person think she is? You know what I mean?”

Not really, but I’m being careful now. This is all very intimate, with eye contact and the touch of an arm or a knee here or there for emphasis, and I’m so distracted that I completely miss the obvious question. “Scarlett, this is lovely, but why are you still here, with me?” It’s the obvious question. But I don’t ask it. We just keep talking until, eventually, she leaves with a light hug and a smile.

The next day, the papers are full of stories about Johansson being photographed on the street without her wedding ring. There is speculation that her marriage to a French businessman is over, which is later confirmed by her agent.

I start to realise that when we met for her interview, she must have been having a really difficult day. I wonder whether she found respite and shelter for a while in a familiar bar, with a friendly stranger she could talk to without giving too much away.

See past yourself

Johansson is a terrific actor, that’s no surprise. As a journalist, I missed the story. As a human being, I failed to see who she really was because my vanity – and that chattering internal chimp – got in the way. So there’s a lesson I take away for any kind of encounter, whether it’s a work interview or a date: be aware of your own feelings and failings, move them aside for a while, let the other person speak and listen – really listen – to what their words, voice, eyes, hands and body language are saying. This is not just good manners, it might also be good for your faith.

Once you get past all the pomp and circumstance, you find a man or a woman trying to make sense of life

The German Jewish philosopher Martin Buber talked about two ways of seeing, which we might call ‘It’ and ‘You’. The first sees the other person for the clothes they wear, the title they hold, the job they do or how useful they might be. The second is all about asking, listening, learning, daring to show who we really are and being willing to see the other as they really are too. It’s difficult to do and risky sometimes, but worth it. And here’s the thing, Buber said: “When two people relate to each other authentically and humanly, God is the electricity that surges between them.”

As a follower of Christ, I believe there is a God out there and in here, in me and you. He is present everywhere – in every molecule, glance, touch, laugh and sunset, waiting to be noticed, waiting for us to realise, waiting for us to hear the music that plays behind all things that, once heard, cannot be unheard. God is indeed in the electricity Buber talks about, if we can find a way to notice it.

God in the small things

The title of my book comes from something that was said about the great Australian writer, Clive James, and his attitude to life in his final days before cancer took him too soon. I met him towards the end and found James “[raging] against the dying of the light” (as Dylan Thomas said). You might expect as much from a man who punched out prose like a prizefighter; but he was also full of a new-found thankfulness. Every moment was potentially precious, as there were so few left. He saw beauty in even the smallest things.

“He never went anywhere, he saw almost nobody, he could eat almost nothing – and yet, every aspect of his life was filled with meaning,” said his daughter Claerwen. “The fact there was an apple on the tree; whether it was rainy or sunny. Everything was extraordinary.” Wouldn’t it be great if we could see like James did without having to wait for the end? The Bible tells us that all creation speaks God’s name (see Psalm 19:1, Revelation 5:13, Psalm 66:4). It also says we are made “in the image of God” (Genesis 1:27), so is there a chance that Buber is right? Opening ourselves up to each other without defence or pretence may open us up to the divine.

I do believe that “deep calls to deep”, (Psalm 42:7). And I have discovered my working life to be a bit like that scene in The Wizard of Oz where Dorothy sees behind the curtain. Once you get past all the pomp and circumstance, fame, fortune and glamour, you find a man or a woman sitting alone like anyone else, flawed and struggling, craving love and trying to make sense of life.

Opening ourselves up to each other may open us up to the divine

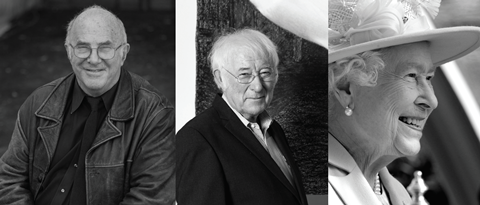

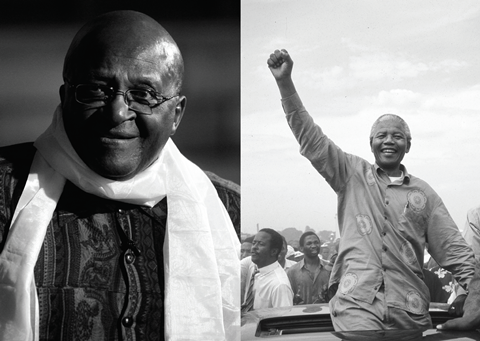

This is true in stories about Tiger Woods seeking redemption, Her Majesty the Queen nodding along while a tiny congregation asks God, in song, to save her, Dame Vera Lynn wondering if it is true that we’ll meet again in heaven, Seamus Heaney flirting at a funeral and talking about how we are all caught up in what St Francis called “the great chain of being”, or Most Rev Desmond Tutu thinking I am trying to kill him. You’ll have to read the book for that one, but suffice to say the holder of the Nobel Prize for Peace screamed for his life as his car drove off in a cloud of dust.

Being human

Tutu and I did meet again on better terms, before the funeral of Nelson Mandela, by which time I had come to love his interpretation of the traditional African concept of ubuntu. “I am because we are,” said Tutu. “Ubuntu is the essence of being human and it says a solitary human being is a contradiction in terms. I can’t be a human being on my lonesome. I wouldn’t know how to speak as a human being. I wouldn’t know how to think as a human being. I wouldn’t know how to walk as a human being. I have to learn from other human beings how to be human – and so ubuntu says my humanity is bound up in yours. I am, only because you are. A person is a person through other persons and we need this communal harmony if we are going to survive at all.”

This idea is at the heart of the book because I have found it to be true in the lives of so many of the people I have interviewed over the years, although not all were aware of it. Superficially, the lives of the rich and famous depend on an army of agents, publicists, organisers, lawyers, accountants, therapists, drivers, cleaners, security guards and, of course, fans – the ones who pay to keep it all going. On a deeper level, those who survive the longest treat their colleagues well, recognise that fame is a team game and find close friends with whom they can open up, relax and be themselves, free of all the nonsense.

I am also very clear about one other thing: the bravest, most compelling and fascinating people I have met have not been famous at all. That’s why I asked you the question at the beginning. Have you thought of an answer? Find me on social media and let me know. I imagine they are someone you know personally rather than from the TV. I might have said my grandfather, Bert, a working-class man from south London, whose life was transformed on the eve of war by a thought shared in a Salvation Army meeting that a pauper like him was as precious as any king.

The bravest, most compelling people I have met have not been famous at all

Then there is Zahra, whose story closes the book. Her family was forced into exile, a story we know well as Christians. Our Lord was a refugee, whose parents fled into Egypt to escape Herod’s murderous soldiers. Zahra crossed the Channel on an overladen rubber boat one Christmas morning, after a 7,000-mile journey that sounded to me like something from an ancient folk tale. A heroine travels a vast distance, overcomes great obstacles, evades monsters and tricksters and proves her bravery before finally finding peace and safety.

We would read and hear stories like that as infinitely inspiring – if we were not told to see people like Zahra as alien and other. They are not. They are us. They are loved like us and, therefore, we should love them too. I know that’s hard to remember when loud voices tell us that certain people are less than human, or that worth lies in fame, beauty, money and power, but these things are simply not true. My faith calls me to resist them.

My working life has taught me to see people, not as labels – Christian or Muslim, right or left wing, young or old – but as fellow human beings, precious and deeply loved, despite all their failings. I honestly believe that’s what Jesus did. And I know that when you sit talking, sharing, listening and really opening up, that’s when the electricity crackles. That’s when there’s a glimpse of the extraordinary, everywhere. And that’s when you might feel that God is near.

No comments yet