Caleb Woodbridge discovers a variety of spiritual messages in TV’s longest-running sci-fi show

On 22 November 1963, a new Saturday teatime “adventure in time and space” introduced a mysterious time-traveller known only as ‘the Doctor’ to TV audiences.

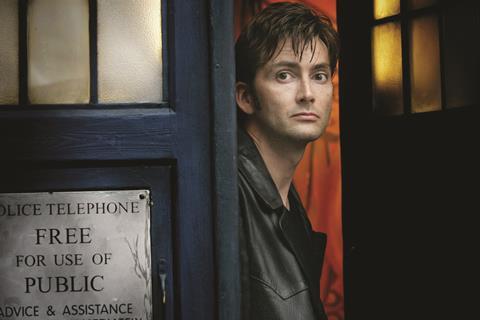

As the much-loved Doctor Who celebrates its 60th anniversary this month, David Tennant returns to the TARDIS, along with Catherine Tate as his companion, Donna. TV writer Russell T Davies is also back at the helm, having previously revived the show in 2005 to great acclaim. With Tennant pulling in old fans, and the announcement of Ncuti Gatwa as the next Doctor likely to attract new audiences – as well a co-production deal with Disney+ to boost the budget and reach global audiences – Davies has a good chance of pulling off another revival. But why is this very British sci-fi institution so enduringly popular?

A spiritual paradox

Throughout Doctor Who’s history, writers have brought various worldviews and outlooks to the show. Like the Doctor’s time machine, the show is “bigger on the inside than the out”, making space for Buddhist and Christian symbolism, as well as a strong streak of atheism and secular humanism (see box).

There is an inherent spiritual resonance and tension to the character of the Doctor. He is hero and scientist; madman in a box and saviour of the universe; alien Time Lord and champion of earth. According to the 1997 Doctor Who movie, starring Paul McGann, he is “half-human on his mother’s side”; while recent showrunner Chris Chibnall revealed the Doctor to be “the timeless child” of unknown origins and untold past lives.

There is an inherent spiritual resonance to the character of the Doctor

A spiritual paradox also lives at the heart of the show. Over the years, the Doctor’s character has developed from that of a mere scientist and explorer into a lonely god; an eternal hero whose legend is whispered throughout the universe. He’s a push and pull between rationalism and romanticism, and the show appeals both to our scientific curiosity and our human longing for a messiah.

This spiritual tension was perhaps most deliberately explored during the Davies years. When I interviewed Davies in 2007 he told me that he considered religion to be: “a very primal instinct within humans, a very good one, part of our imagination,” adding: “I’m not an enemy of that instinct that tells us to look upwards.” So perhaps it’s not surprising that Davies’ version of Doctor Who had a theological bent, even if from a secular humanist perspective.

Let’s explore some of his most Christian-inflected moments.

‘The lonely god’

In ‘New Earth’, David Tennant’s second episode as the Doctor, Davies introduces the idea of the Doctor as ‘the lonely god’. A legend has grown up around the Face of Boe, one of the oldest creatures in the universe, that before he dies, he will share his last great secret with “a wanderer…the man without a home, the lonely god”. The Doctor realises that this message is meant for him.

That secret is revealed in the following season’s episode ‘Gridlock’, one of Davies’ most direct explorations of religion. The Doctor and his new companion, Martha Jones, become separated, both trapped in the eternal traffic jam of New New York in the year 5 billion. The people in their flying cars are in denial of the truth: they are going round and round with no escape. They find comfort in singing hymns together, but their faith makes them passive to their predicament.

As Martha tries to make her way back to the Doctor, she tells the trapped drivers: “You’ve got your faith, you’ve got your songs and your hymns, and I’ve got the Doctor.” The Doctor’s actions help save the day – though it takes the Face of Boe sacrificing his own life to free the people of the motorway. In this way, the story paradoxically echoes the gospel and suggests that faith is a barrier to us solving our own problems.

The many worldviews of Doctor Who

1960s

Early Doctor Who embodies 1960s space-age optimism, a modernist confidence in the power of science – though shot through with dystopian fears and the shadow of nuclear war.

Early 70s

Producer Barry Letts’ Buddhism comes through in the Jon Pertwee era, with the Doctor’s regeneration becoming a symbol of the reincarnation cycle of death and rebirth.

Late 70s

The Tom Baker era shows a strong atheistic streak under script editors Chris Boucher and Douglas Adams, with mad gods turning out to be evil aliens or malfunctioning computers.

1980s

Later classic-era Doctor Who begins to show the postmodern turn – in the episode ‘The Curse of Fenric’, it isn’t Christian faith or symbols that hold off the vampiric haemovores, but faith in general, whether in Communism, the Doctor or friends.

1990s

The 1996 American TV movie leans hard into Christian symbolism, with a Satan-like Master, and Paul McGann’s Doctor emerging newly regenerated from a morgue, wrapped in a shroud.

2010s

Steven Moffat, showrunner for Matt Smith and Peter Capaldi’s Doctors, explained his love of twisty-turny plots with unreliable narrators to an audience Q&A as being because: “Spoiler alert! There is no God!” and therefore no one true version of events.

2020s

Jodie Whittaker’s era saw the show take a more diverse and inclusive approach, including more sympathetic portrayals of faith. In the episode ‘The Tsurunga Conundrum’, the Doctor joins in with a closing prayer that says: “May the saints of all the stars and constellations bring you hope.”

‘Like fire and ice and rage’

In the two-part story ‘Human Nature / Family of Blood’ later in the same series, the Doctor is on the run from the Family of Blood and becomes human to hide in 1913, believing himself to be the schoolteacher John Smith.

As Smith, he falls in love with nurse Joan Redfern, much to Martha’s dismay as she watches on, undercover as Smith’s maid. But when the Family of Blood track him down, the Doctor is faced with an agonising choice – he must give up the human life that he longs for, with human love, family and mortality, to become the Doctor again. Smith must die to save others, but he will be reborn as the Doctor.

This story was written by Paul Cornell, who has previously been described as an Anglican with pagan sympathies. When promoting the episode, Davies described it as “basically the story of Christ”.

Doctor Who presents a great opportunity to open up conversations

The episode also contains a description of the Doctor by Timothy Latimer, a pupil of Smith’s. He says: “I’ve seen him. He’s like fire and ice and rage. He’s like the night and the storm in the heart of the sun. He’s ancient and forever. He burns at the centre of time and he can see the turn of the universe. And he’s wonderful.”

It’s heavily reminiscent of the description of Jesus found in Revelation 1:13-16: “The hair on his head was white like wool, as white as snow, and his eyes were like blazing fire. His feet were like bronze glowing in a furnace, and his voice was like the sound of rushing waters. In his right hand he held seven stars, and coming out of his mouth was a sharp, double-edged sword. His face was like the sun shining in all its brilliance.”

‘Is that your weapon – prayer?’

The season finale ‘The Last of the Time Lords’ sees the Doctor go head-to-head with the Master, his friend and fellow Time Lord turned evil megalomaniac. The Master takes over planet Earth, imprisoning the Doctor and ageing him into a Dobby-like creature. The Master enslaves the human race as his first step in conquering the universe. This leaves Martha Jones to wander the earth fermenting rebellion and spreading a message of hope, telling everyone to think the word ‘Doctor’ on a particular time and date.

Captured by the Master, he scoffs at “Saint Martha’s” plan: “That’s your weapon – prayer?” But in a typical bit of Doctor Who technobabble, Martha and the Doctor turn the psychic Archangel network that the Master has used to keep humanity docile against him. Humanity’s belief in the Doctor makes him ascend in a glow of psychic energy, restored to his normal self, as he reaches out and offers forgiveness to the Master.

Don’t mistake any of this for Christian allegory: it is the power of humanity’s belief that saves the day, not any intrinsic power of the Doctor to save them or himself. And as other Doctor Who stories demonstrate, the Doctor is a very fallible saviour: it is in part his hubris, in believing his own hype, that leads to his downfall in later episodes ‘The Waters of Mars’ and ‘The End of Time’. As Monty Python might put it, he’s not the Messiah, he’s a very naughty Time Lord!

Why it matters

Whether this subversive use of Christian imagery will resurface in Davies’ new scripts remains to be seen. But Doctor Who presents a great opportunity for Christians to open up conversations about our desire for heroes and messiahs.

As we discuss the show with friends and fans, we can ask: “What if there is a real saviour who, like the Doctor, overcomes not through violence but through kindness and self-sacrifice?” or: “What if there is a true Messiah who can satisfy both our imaginative longing for a hero, and our rational longing for someone real, who objectively stepped into the pages of history?”

The Doctor’s words of invitation from the 2005 TV trailer echoes Jesus’ call to follow him: “Do you wanna come with me? Because if you do, I have to warn you – it won’t be quiet, it won’t be calm, it won’t be safe. But I’ll tell you what it will be – the trip of a lifetime!”

In the Doctor, we have an echo of the true and better Time Lord: Jesus Christ.

The 60th anniversary Doctor Who specials are set to air on the BBC in November, while Gatwa’s first official episode as the Doctor will be broadcast during the festive season

No comments yet