Maddy Fry reveals the untold story behind Bruce Springsteen’s mysterious soundtrack Faithless, written for an unmade Martin Scorsese film about a Catholic nun and an outlaw

Well into his seventh decade, the Boss isn’t keeping a low profile.

This month sees the release of Deliver Me From Nowhere a biopic about the difficult birth of his early-80s masterpiece Nebraska.

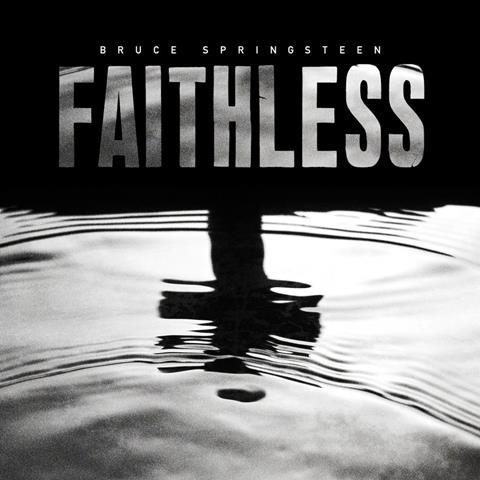

Yet another film project had been brewing for decades, almost unnoticed. Earlier this year Springsteen released Tracks II, a deluge of buried material that despite glowing reviews, contained a 2005 album skipped over by most music pundits: Faithless, the soundtrack to a Martin Scorsese film that was never made.

Little commentary has emerged about why, and Springsteen has remained tight-lipped. The deepest any critic has gone is to say that the phantom film was meant to be a ‘spiritual western.’ The most popular online rumour is that it was based on Thomas Eidson’s novel St Agnes’ Stand, a gory, twisted buddy caper set in the Old West where an outlaw teams up with a Catholic nun.

When Premier approached Colin Vaines, head of development at Miramax when the project was optioned, he confirmed Eidson’s novel as the source material. Judi Dench was even a contender for the role of Sister St Agnes. Yet the film was dropped because it just “never went anywhere.”

The reasons are partly rooted in the kafkaesque wormhole of film financing. According to Vaines, “it was in development for a long time, and there was definitely the intention that John Madden would direct it post-Shakespeare In Love.” When John Madden lost interest, it was given to Asif Kapadia (best known for the biopics Senna and Amy) but Miramax disliked his treatment. “I think it just came to a point where it had been hanging around for a long time, costing money to keep renewing, and finally Miramax let it go,” said Vaines.

When the option lapsed, it was picked up by Scorsese at Dreamworks. Yet the film’s themes might have hampered its box office potential. It is, says Vaines, “quite dark. There seemed to be a lot of question marks over its commerciality.”

A glance at the book backs this up. Co-protagonist Nat Swanson, a Texan murderer journeying to California in a bid to shake off his captors, sees up close what happens to any wagon that crosses paths with the local Apaches. Published in 1994, the novel’s one-dimensional treatment of Native Americans would not pass present-day standards. The depictions of castration, rape and beheading are unflinching and Nat’s chance to help Sister St Agnes ensure a group of orphans avoid this fate while under her care is the only form of respite. The two regularly debate life, death and faith, but doubt and damnation never seem far away, even for the indefatigable woman in the wimple.

Why would Springsteen have shown an interest? In his 2016 memoir Born to Run, he said he was still “on the team” when it came to Catholicism and that he had a “personal relationship with Jesus.” Ken Womack, author of Bruce Springsteen, Cultural Studies and the Runaway American Dream, says that it seems like a natural journey for the Boss to take: “(Faithless) is in line with the moral evolution that begins with The Ghost of Tom Joad into the present day, where Springsteen grapples with the realities of living and being in an often unforgiving ethical landscape.”

It could also be a mirror to Scorsese’s body of work. His 2016 film Silence, about the persecution of Jesuit missionaries in 17th century Japan, gives us a strong sense of what Faithless might have said about belief, and the kind of sacrifices required to hold onto it in a world of no guarantees.

What might the ‘lost’ film have looked like? The soundtrack for Faithless was apparently written with “atmospherics” in mind rather than a coherent plot, but the songs frequently map onto the journey followed by Eidson’s two main characters. Says Womack, “the music and lyrics seem to connote Sister St. Agnes’s own struggles with faith and redemption.” In the book she confesses to Swanson that she had been about to leave the convent before his arrival, which she sees as a direct intervention from God - an inner journey reflected in the lyrics of the tracks ‘Faithless’ and ‘God Sent You.’

Anthony Pami, a New Jersey-based Methodist pastor and commentator on Springsteen, adds that the song ‘My Master’s Hand’ seems to have Swanson “finding some resolution that his work is to be the ‘hand’ of God (of love) and that what he builds with his hands and his heart can’t be separated from what God desires for him in his life.”

For anyone who finds this subject matter compelling, it is a great shame that the project never saw the light of day. Furthermore Womack says the lack of interest in the soundtrack by critics is unsurprising. Springsteen’s thoughtful, undogmatic musings on religion seems like a throwback to a less divided era: “Faith—especially the issues that Springsteen speaks of—involves, by its very nature, issues of mystery. These concepts seem like a bridge too far in our contemporary moment, where people seem determined to speak in absolutes.”

Yet according to Vaines, the book is presumably “free to be optioned again.”

In a more forgiving future, resurrection might yet be possible. Until then, there’s Faithless.

No comments yet