I was nine years old when Stephen Lawrence was murdered, 30 years ago this April. It was the early 90s, and far-right extremist groups were making a resurgence in many parts of south-east London, including Eltham, where I lived, and where Stephen was killed.

As a West African immigrant family, it was a pretty scary place to be. We lived in fear of skinheads and racist thugs. We learned how to look straight ahead if we were in the proximity of people who looked like they might be National Front or BNP members, so we didn’t draw attention to ourselves.

Stephen’s murder – and the subsequent Macpherson inquiry into institutional racism within the Metropolitan Police – formed a tragic backdrop in the lives of Black Britons. It has always been there, a symbolic reminder that we have never been fully accepted as those with brown skin in a nation of whiteness.

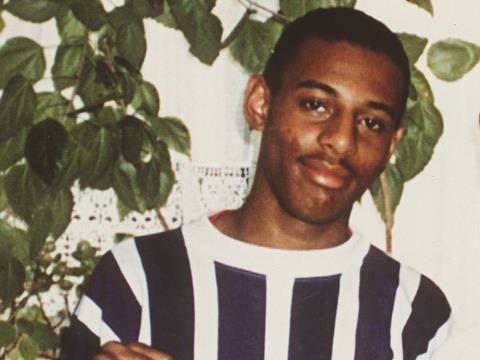

I often drive past the bus stop where Stephen was killed. I picture his last moments and I think about that iconic photograph we have all become so familiar with: a young man, who should have had his whole life ahead of him.

The past 400 years have told a story of brutality and oppression that reaches through the centuries and continues to have a visceral effect on Black people, including those in our own church congregations.

While writing God is Not a White Man (Hodder & Stoughton), I remember standing in my kitchen, shaking with trauma. I had spent weeks researching violence against Black people – from the hellish experiences on slave ships through to enslavement itself; from lynchings and hanging trees to the more recent deaths of Stephen Lawrence, Eric Garner, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd – and many more.

Some white people were confused by the visceral response of Black Britons to the death of George Floyd. After all, this tragedy happened thousands of miles away. But throughout our lives, we have seen too many instances of violence against Black people; the last moments of their lives caught on camera and broadcast in a way you would never see a white person’s murder.

When we watched George Floyd’s murder, we saw our own necks on the line. Perhaps, collectively, it was the last straw. We felt connected in a way that can only be understood within oppressed groups.

Monnica Williams, a professor and psychologist, calls it “vicarious trauma”: race-based stress, triggered by viewing racial discrimination, brutality, violence or aggression through a third party, such as social media or the news. She suggests that racism should be included as one of the causes of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

I have seen the weight of this trauma on Black people in our churches many times over the years: the righteous anger that pours out of us at unexpected times when we talk about the brutality against people like us.

We need you to understand the weight of this fear and pain. As US theologian and historian Jemar Tisby told me: “Black people respond so vigorously to any hint of racism because we know, deep in our souls, that the logical end of white supremacy is Black death.”

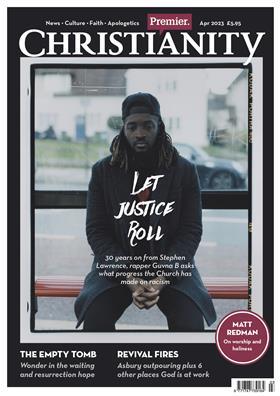

For more on this story, see the latest issue of Premier Christianity, which features a cover story by Guvna B reflecting on 30 years since the murder of Stephen Lawrence. Subscribe here

No comments yet