Alexander McLean isn’t just binding up the broken-hearted inside African prisons. He has also been setting some of the captives free. Sam Hailes hears the full story

The sight that greeted an 18-year-old Alexander McLean as he walked into a Ugandan hospital is almost too horrendous to imagine: a man was lying on the floor by the toilet. He was naked and lying in a pool of urine. The flesh on his bottom and back was rotten down to the bone. He was decomposing while he was still alive, a nurse had told him: ‘We think he’s in a diabetic coma. We don’t know his name, we’re waiting for him to die. He doesn’t get care because he doesn’t have any money,’ she said.

Six days later, the man passed away. A hospital porter arrived, pushing a trolley with a dead woman on top of it. McLean, now 34 years old, remembers: “He put the man on top of the woman and said they’re both going to a mass grave with everyone else who had no one to bury them. It was really a turning point in my life. I realised that there are people in our world whose lives have no value and who live and die like dogs. I remember calling my mum that evening and crying for him.”

JESUS GIVES US A REALLY CLEAR REMIT AS CHRISTIANS TO SERVE THOSE IN PRISON

McLean had left his comfortable home in the UK to volunteer inside Uganda’s hospitals. The teenager’s initial trip was supposed to last just two weeks, but soon turned into six months. In the course of his volunteering stint, McLean met prisoners who had been sent to the hospital for treatment. Many of them were teenage boys convicted of having underage sex (a crime that can carry the death penalty). Most Ugandans identify as Christian, and church attendance is high, yet McLean observed some groups of people had been “deemed unworthy of love”.

As McLean formed friendships with the prisoners at the hospital, he discovered they were just like him: “They had similar hopes, and fears and dreams. I thought it would be fascinating to go to the prison they came from. So I bulldozed my way into Uganda’s maximum security prison.”

ON THE INSIDE

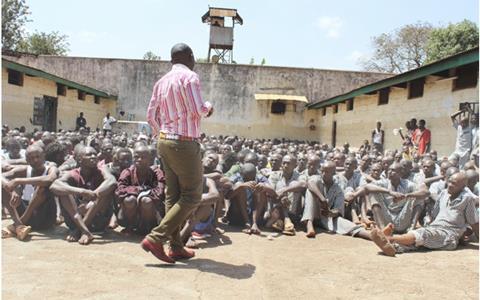

The prison in question was built by the British in 1928 and was designed to hold 600 prisoners. When McLean arrived in 2004, there were 4,000 inmates crammed inside, living in squalid conditions. “As I walked in, a teenage boy who had died was being sewn up in a blanket to be buried in. It was just a horrible environment. No one deserves to die in such a place.” Over the course of the next few years, McLean took it upon himself to overhaul prison hospitals. He visited more than 100 prisons around the world: “I’ve seen things which have broken my heart again and again and again. I’ve been in countries where prisoners die of suffocation because the cells are so crowded that there’s not enough air. I’ve been in prisons where women have given birth on the floor of their cells, and their children die because they don’t have access to the most basic treatment.”

But after working for years to improve conditions inside African prisons (and seeing death rates drop as a result) McLean realised there were other, even more serious problems that needed addressing. He met one man, accused of murder, who’d spent twelve years on death row. It came to light that the person he’d been accused of killing was still alive, but it took another six years before justice was served and he was finally released. McLean discovered that cases such as these weren’t unusual and that two-thirds of prisoners in Uganda were still awaiting their trial. Furthermore, in many of the postcolonial nations where Mclean was working, innocent people were being locked up as a direct result of archaic British laws. It was Britain who had made attempting suicide a crime, for example.

Injustice was all around. A South Sudanese woman he’d met had been sentenced to death on her husband’s behalf because the police couldn’t catch him. “So they caught the wife and she was to die in his place.” He also met inmates who had sold everything they had in order to pay a lawyer, only for the lawyer to run off with the money and never be seen again.

“We began to wonder: what does it look like to take those who have suffered at the hands of the State, who’ve had their fingernails pulled out in the police station, or who’ve been convicted of a crime they didn’t commit, to be given high-quality legal training to equip them to bring justice while in prison, and upon release, and to create a transfer of legal knowledge, which is power, from the centre of society to the margins?”

McLean’s next step was to create African Prisons Project (APP), a charity that provides legal training for prisoners. “We also put prisoners through University of London law degrees, studying remotely as Nelson Mandela did when he was imprisoned in South Africa, wondering what might happen,” he explains. “In total, we’ve seen about 10,000 people so far released from prison in Uganda and Kenya after accessing legal support from our paralegals.”

On top of assisting prisoners to quash their unjust convictions, the project has also had a profound effect on those tasked with implementing justice, as McLean explains: “I think about one of the prison officers we work with. She said, ‘Before you trained me in law, I used to torture prisoners. Now I take great joy in going to court to speak on their behalf and win them their freedom.’”

Several students, such as Susan Kigula, have had their death sentences overturned. “She became one of the university’s best-performing students in human rights law and was able to establish an informal Legal Aid clinic at her prison,” McLean explains. “She went on to challenge the mandatory death sentence for murder and armed robbery in Uganda. Formerly a judge had no alternative but to sentence someone to death if they’d been convicted of one of those offences. But as a result of Susan’s case, the mandatory death sentence was abolished. And now judges always have discretion as to whether to give the death penalty or not.”

A QUIET, STRONG FAITH

McLean attributes any confidence or courage he might have to the influence of his late grandmother. “She loved me fiercely,” he says. She may well have been guilty of “overpampering” and “spoiling” him, but she also modelled what a “quiet, strong” faith could be. McLean describes her lively, Pentecostal funeral as “more Volunteer of the Year, UK Young Philanthropist of the year and a spot in TIME magazine’s 30 under 30, but he says: “I feel most alive when I’m in prison. Jesus gives us a really clear remit as Christians to serve those in prison. And the times I have been in prison make me more courageous.

GOD USES THOSE WHO SCREWED UP…WHO ARE WE TO WRITE PEOPLE OFF?

I’m inspired by the resilience and the resourcefulness of the people in the community that I belong to.” McLean doesn’t downplay the seriousness of the crimes that have been committed by some of the people he works with. “I belong to a community of people who have stolen, who’ve killed, who’ve raped, who’ve tortured,” he says, adding: “I think our starting point is that none of us is good. I can’t say: “My sin is insignificant, but yours is really bad, so I can’t engage with you.’ It’s about acknowledging that even those who’ve made tremendous mistakes can also do great good. If we look at the Bible, we see God uses those who screwed up, often quite significantly. Paul was the equivalent of an IS member today – persecuting and killing Christians – but then was used very powerfully.

Who are we to write people off?” McLean isn’t naïve enough to believe everybody he works with is innocent. He has a law degree from the University of Nottingham and works as a magistrate in the UK. “My job here is to send guilty people to prison,” he explains, adding: “So my interest is in justice. I think there’s a role for prisons. And I think the law can be a powerful tool. I think it’s appropriate that people are punished and that there are consequences for wrongdoing, but I think the punishment should be proportionate. I think everything about prison should be about equipping the person for life afterwards.” vibrant” than the Anglican services he’d been used to previously. Inspired and interested by this new, unfamiliar expression of Christianity, he joined New Testament Assembly in Tooting. “I fell in love with church and what it means to be part of a community that loves God, loves each other and is trying to bring love and light into the world.” McLean’s work has led to multiple accolades, including UK Chari Volunteer of the Year, UK Young Philanthropist of the year and a spot in TIME magazine’s 30 under 30, but he says: “I feel most alive when I’m in prison. Jesus gives us a really clear remit as Christians to serve those in prison. And the times I have been in prison make me more courageous. I’m inspired by the resilience and the resourcefulness of the people in the community that I belong to.”

McLean doesn’t downplay the seriousness of the crimes that have been committed by some of the people he works with. “I belong to a community of people who have stolen, who’ve killed, who’ve raped, who’ve tortured,” he says, adding: “I think our starting point is that none of us is good. I can’t say: “My sin is insignificant, but yours is really bad, so I can’t engage with you.’ It’s about acknowledging that even those who’ve made tremendous mistakes can also do great good. If we look at the Bible, we see God uses those who screwed up, often quite significantly. Paul was the equivalent of an IS member today – persecuting and killing Christians – but then was used very powerfully. Who are we to write people off?”

McLean isn’t naïve enough to believe everybody he works with is innocent. He has a law degree from the University of Nottingham and works as a magistrate in the UK. “My job here is to send guilty people to prison,” he explains, adding: “So my interest is in justice. I think there’s a role for prisons. And I think the law can be a powerful tool. I think it’s appropriate that people are punished and that there are consequences for wrongdoing, but I think the punishment should be proportionate. I think everything about prison should be about equipping the person for life afterwards.”

No comments yet