Some Christians are concerned about the pagan overtones of the Green Man positioned at the foot of the King’s coronation invites, but let’s not be scornful of this symbol, it might just open up a fruitful evangelistic discussion, says Tony Wilson

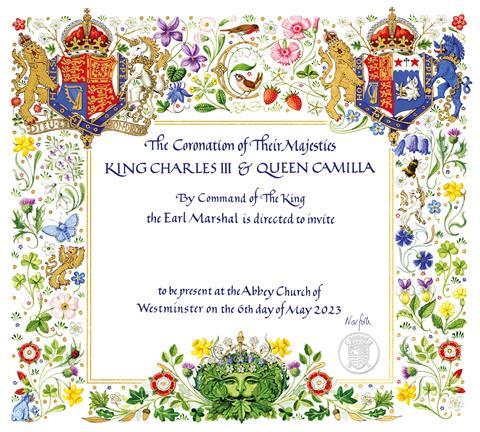

Catching a glimpse of the recently published invitation to the coronation of King Charles III, I was immediately drawn in by the exquisite design by Andrew Jamieson. Flowers, birds, bees and butterflies representing all the nations of Great Britain spill across the card in a celebration of life and colour. But perhaps the most prominent feature is a representation of the Green Man, which is causing some concern among Christians.

The official royal website says: “Central to the design is the motif of the Green Man, an ancient figure from British folklore, symbolic of spring and rebirth, to celebrate the new reign”. We might expect such a choice from a King who has shown a lifelong concern for the natural world and environmentalism but we might equally wonder why a character with pagan overtones was picked.

Who is the Green Man?

The history of the Green Man is obscure and certainly predates the modern revival of the Arts and Crafts movement, maypoles and morris dancing. Images of a man with foliage sprouting from his hair and mouth, largely propagated by stone masons, spread across Europe from the Near East during the medieval period. Rather like the legendary figures of King Arthur and Robin Hood it is impossible to trace the origin of the Green Man to a single source or to identify any role he played in paganism.

While it’s easy for us to see this as yet another way in which the Christian dimension of the coronation has been diluted, I think we can come up with a more positive way of engaging. The Apostle Paul was quick to use the statue of the unknown God (Acts 17) as a springboard for preaching the gospel to the people of Athens and this might be our opportunity to do the same.

Paul was able to take something familiar to the people he was seeking to reach and point out how the God of Christianity is distinctive. To the extent that the Green Man has been adopted by modern expressions of paganism, we can point out some key differences with our faith.

Paganism and pantheism

The personification of nature in the Green Man reveals an aspect of paganism that sets us poles apart. Pantheism, the idea that God is located within and throughout the physical world, is central to many kinds of paganism. This belief system can encourage people to see plants and animals as objects of worship. In contrast, for Christians the natural world can inspire us to worship the creator.

One danger of folklore myths is that they lurk around in the psyche of the people and distort our theology. The insistence in the Old Testament that the Jewish people maintained a separation from the gentiles (non-Jewish people) was almost certainly to nurture some very new, fragile and distinctive ideas about the kind of God that was being revealed to them.

One common misconception among atheists is that God is just one thing in the inventory of things in the universe. If we look hard enough with the toolkit we use to discover things about the world then we should find him. But we don’t. So he isn’t there.

The problem is that the Green Man, and all other forms of animistic beliefs within paganism, allows these kinds of ‘category mistakes’ by well-meaning people. We have to gently replace these distortions with ideas rooted in Christian theology before we can make a fruitful presentation of the gospel. We have to start with the transcendence of God who is utterly beyond and distinct from the universe. There is God and then there is everything else.

The Green Man nudges us to worship creation but we must resist

But just pointing out our differences leaves our story incomplete. We can also find some common ground. God did choose to make a physical world from real stuff, and he called it all “good”. He did call us to look after it, so we can appeal to a common concern to be responsible stewards, humbly accepting that we haven’t always followed his commands to protect our planet.

Much more than this, God not only made a physical world, he chose to redeem it through the incarnation. The birth, life, death of Jesus brings God within his creation – he is not only transcendent, he is imminent. He forms an association with the physical world. Most importantly, Jesus’s resurrection and ascension forms the bridge between the created world and the transcendent creator.

The Green Man nudges us to worship creation but we must resist. We can be confident that the material world, in all its glorious diversity and beauty, is loved by God and was endorsed by him in the person of Jesus. Our physical bodies are important and so is the stuff around us. God works daily miracles in the ordinary stuff of water, oil, bread, wine and, through our hands – transcendence meets imminence.

Let’s not be scornful of the Green Man. He might just open up a fruitful discussion.

2 Readers' comments