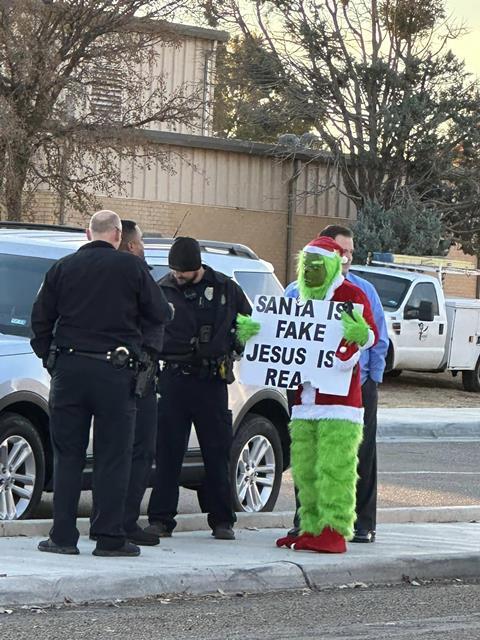

A man dressed as The Grinch has caused controversy for standing outside a school in America with a placard proclaiming: “Santa is fake. Jesus is real”. It might be the truth, says Emma Fowle, but it’s not a great way to share your faith this Christmas

When our eldest daughter was small, my husband and I began discussing our parenting strategy as it would relate to Christmas. Having not been raised in a Christian home myself, I didn’t have a point of reference from which to learn, but I was keen to ensure that our children fully understood that Jesus was the reason for the season, not Father Christmas.

With the best of intentions, I was, perhaps, a little over-zealous in the early days. I wanted nothing to do with Santa, I informed my husband, and we would on no account be endorsing the lie that he was real. After all, if we’re not truthful about this, what chance do we have of our children believing what we tell them about Jesus?

Honest truth

It’s an argument that is commonly debated among Christian parents. But how does the decision to be honest about Santa play out on the school playground, in toddler groups, and among your friends and family who don’t follow Jesus? #

Could being brutally honest ever be a bad evangelism strategy?

My husband definitely thought so. “Are you kidding?” he said to me when I told him our children would never be raised to believe in Santa Claus. “Do you seriously want them to be the most hated kids in the playground? How is that ever going to be a good advert for Christianity?”

He had a point. It was one thing to want to be honest with our kids, but it was also important to think about the culture and context in which we lived. In order to debunk the ‘Santa myth’, we’d have to sit them down at a very young age and, very clearly and explicitly, tell them he was not real, despite what adverts and songs and Christmas grottos and Santa’s annual visit to their pre-school might suggest.

In doing so, we had to face the very real possibility that they’d then communicate that, with little tact or explanation, to their young friends – possibly dashing their own parent’s carefully-crafted Christmas traditions and creating a trail of tears in their wake. The conversations at the school gate might not be pleasant. More importantly, it didn’t seem a good way to win friends and influence people. Did we really want to be known as that Christian family who ruined Christmas for everyone? Where would we go from there when it came to sharing our faith?

Going against the grain

There are times when Christians will undoubtedly need to stand up for the truth and go against the culture. I do not believe that we should lie to make life easier for ourselves or more pleasant for others. But I do think we should pick our battles. And breaking the young hearts of other people’s children – incurring the wrath of their parents in the process - was, we decided, not the fight we wanted to pick.

As our children have grown and progressed through their school life, there have been many legitimate areas of concern. Whether it’s discussing the contents of school sex education lessons or negotiating dating boundaries, there are so many places that our Christian faith sets us apart. Communicating our deeply held convictions to those who do not share our faith - in a way that does not make Christianity just seem like a set of boring rules and regulations - can be difficult. Maybe being a Grinch at Christmas is one hill we don’t need to die on.

The right focus

So what did we decide to do instead?

For us, we decided on a ‘neutral’ approach. That meant, within our own four walls, neither overly celebrating nor overly denigrating Father Christmas. We steered away from encouraging the writing of letters, visits to Santa’s grotto or overly elaborate rituals such as the fake eating of cookies or the creation of footprints on the fireplace.

We told our children that their birthday was ‘their’ day, when they could expect their largest gift of the year, and Christmas was Jesus’ birthday, so the focus would be on him. We celebrated it by going to church and giving (lovely, but not overly extravagant) gifts to each other. The presents under the tree were always from Mummy and Daddy, never from Santa.

At the same time, we did not prevent them from taking part in anything that happened in school, and neither did we go out of our way to quash the childhood Christmas magic. They always had a stocking that was ‘miraculously’ filled at some point during the night of Christmas Eve and opened with much excitement in the morning.

At some point, they worked out that it wasn’t delivered by reindeer and a sleigh, and that Santa wasn’t real. It didn’t cause a whole load of consternation nor a crisis of their faith – perhaps because the Christmas traditions that we have chosen to intentionally create as a family have been far more anchored around our faith than Father Christmas.

And for me, that’s a much better witness to our friends and family who don’t believe than spending the festive season shattering young children’s dreams.

1 Reader's comment