The critically acclaimed author talks about swearing, messing up his marriage and why Christian art is sometimes a little bit rubbish

Francis Spufford is a child of his times. He was raised on a university campus by “serious and convinced” churchgoing parents, in an era when Christianity was “taken for granted” as part of most people’s ordinary lives. Spufford’s childhood love of books – most notably CS Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia – was, in part a refuge from his younger sister’s illness (she would later die of cystinosis, a rare genetic condition, aged just 22). His childhood faith existed in tandem with these fictional worlds. “I would have been very happy if God just was Aslan,” he tells me, before admitting that this escapist faith had mixed results.

His teenage years began two decades in which God was absent from the writer’s life, despite his marriage to a fellow academic whose own faith would lead her to become an ordained minister.

In his 30s, Spufford committed what he calls a “classic, destructive male mistake of midlife”. He politely declines to provide any further details other than explaining: “They are my shames, but other people’s privacy is involved.” That the crisis somehow led him back to God is both a miracle and a testament to the creative ways that a creative God breaks through into our everyday, he says.

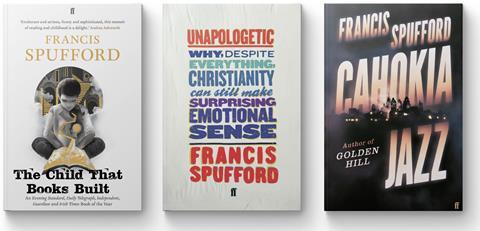

A professor of creative writing, Spufford has authored award-winning fiction and non-fiction that spans many genres. His infamously sweary Unapologetic (Faber & Faber) was a response to Richard Dawkins’ bestseller The God Delusion (Black Swan). In it, Spufford memorably defined sin as “the human propensity to f*** things up” or “The HPtFtU” for short. Was he trying to become the Bono of Christian apologetics, I ask? He squirms slightly and laughs. “Maybe…”

Over a decade later, he’s not sure he’d plump for the same shock-and-awe tactics (“It was the best idea I could come up with at the time,” he says with a wry smile), but he stands by the need for Christian creatives to tell the truth in their art. Christianity does not need “a polite, nervous little voice,” he says. It’s time to reclaim our cultural confidence, and become more certain about proclaiming a God who is comfortable with the whole of human experience, “even the dark bits”.

You rejected the Christian faith in your teenage years. What made you return to it?

I’m in my mid-30s, I’ve got married, and I perform one of the classic, destructive male mistakes of midlife. My marriage is in terminal trouble. I have messed things up completely and for good, when the news that there might be something to hope for comes to me, sitting miserably in a café, in the form of Mozart’s ‘Clarinet concerto’ – which [novelist Richard Powers] once described as “the way mercy sounds”. It’s a completely realistic bit of music. It doesn’t go: “Everything’s fine”, it goes: “Everything’s not fine, you really have made the mistakes you’ve made, but there is more to the story than that. There is mercy in the world which you don’t have to deserve.”

Why should Christian books always be so overwhelmingly well behaved?

I had the advantage of having been a believing child, so it was churches that I wandered into. It took me a little while to discover that the message I was getting, courtesy of Mozart, was ultimately coming from God. I realised that there’s nothing childish about Christianity at all. It is a profoundly realistic religion where human behaviour is concerned, and it is just there, waiting for adults who mess up and see no way out.

Bit by bit, I discovered that Christianity gave an account of what it was to be human that seemed more true, more complete, more wise, more kind and more satisfying than any of the other ones.

Did you find your way back to faith on your own, or did you have people who helped you?

Well, my wife, with whom I’d made such a terrible mess of things, is a believer. She is a cathedral canon now. She has always been a large influence on my faith…

You’ve known each other since university, so how did that work during your atheist years?

She didn’t push it, which was wise. And she wasn’t always the right person to talk to about it when I started my journey back…but I’ve been a vicar’s husband for nearly 20 years, so it’s not like we didn’t get it together in the end.

What’s that like?

It’s slightly weird, in that I’m a lot less holy than she is! There is a kind of church umbrella that the minister’s family finds themselves underneath, which is not always the easiest place to grow up – as my daughter has found out. You find that you’ve entered a slightly weird family business where attempting to manifest the love of God is kind of what you do. I’m not always that good at it.

It’s interesting talking to a man about this because, often, we hear about the expectations placed on church leaders’ wives…

Men have a much easier time of it, thanks to the evils of the double standard! Nobody ever asked me to be president of the guild of needlewomen or do the flower arranging, and if I could be at all competent cooking a lasagne for twelve people, people would say: “Oh, well done!” I did actually run the Sunday school at one point, but people were surprised and delighted rather than going: “Well, naturally, he’s doing it.” Vicars’ husbands have twice as easy a ride as vicars’ wives.

Let’s talk about Unapologetic. Did you get much pushback from the Christian community over the swearing in it?

A little, but far less than I expected. When I was writing it, the Richard Dawkins wave was at its height. There were lots of responses to The God Delusion which were painstakingly careful and full of philosophical arguments, but none quite did the job for me. I thought: Why should Christian books always be so overwhelmingly well behaved?

Some of the things that go by the name of Christian art are not very good

We shouldn’t be nasty or evil, but if people’s ideas are ridiculous, we ought to say so. I set out to write something that was fast on its feet, funny and occasionally mischievous. But was the swearing really necessary? It was a solution to telling people that Christians don’t always speak in soft, restrained voices, and that our faith does not exist in some sort of glass dome, where any loud, sudden movement might suddenly shatter it. I’m not sure it was the best way, looking back 13 years later. Ever since, people have been slightly disappointed that I’m not quite the persona they met on the page. I am a bit sweary, but I’m not that sweary. I never swear in church and I draw a hard line between profanity and blasphemy. That’s not OK.

But it sort of did the job, not being in the tone of voice that people were expecting.

There is something about taking an unexpected approach to grab people’s attention, and I think there is an assumption that Christian art has to be nice and kind and polite…

We do have to be kind. We have to desire good, even for those who are persecuting us and being a total pain in the ass, but we don’t always have to do it by being sweet. We can also have a laugh.

That stereotypically ‘nice and polite’ image of Christianity can be off-putting for many people, as it is not something that necessarily relates to their life…

Indeed! It’s also cobblers, to use a technical, theological term. Christianity is about the whole of human life; it is not afraid of the dark bits, the messy bits, the untidy bits, the bad-tempered bits, the dull bits, the troublesome bits, the bits whose meaning you really can’t work out, but trust that God can. It’s big and realistic and unafraid of anything that the human condition can throw up. That doesn’t sound to me like a recipe for a polite, nervous little voice.

So you’re saying God is not as easily offended as we may sometimes think he is?

I don’t think God is offended, in the human sense, by anything. We are assured that there is literally nothing we can do that will cause God to give up on us. There are obviously things that God would prefer we don’t do, but he seems to be committed, luckily for us.

But there are obviously things that he doesn’t like in us and would have us change?

Yes, but it’s never a reason to turn away. There’s no parable that goes: “We won’t bother to track down that lost sheep, because that’s a rather unsightly one.” No.

We are classically bad at working out what our most important sins are. The things we [feel] most guilty about may well be a mere sideshow compared to the stuff that God would most like us to change.

All of human life is open for intelligent and wonderful Christian artistry

How does your faith intersect with your creativity?

I used to say: I’m not a Christian writer, I’m a writer who happens to be a Christian. But that can’t be quite true, because my Christianity doesn’t exist in a box, which I close when I write. It influences the way you understand everything so, naturally, it influences the way I write and what I write about.

I tend not to be to be drawn to stories about people trying to lead the perfect Christian life. I write stories that have got a theological bottom layer – like an underlay in the carpet of the story – which the characters don’t necessarily know is there. As a Christian, I am helplessly, endlessly telling stories which are like tracings of the gospel story, even if it’s not visible to most readers – or even to me. When I get towards the end, I think: Oh, I’ve told that story again, it’s redemption, isn’t it?

What is your favourite Bible story?

The woman taken in adultery. It is not a fun story, but it is a life-or-death illustration of what God’s priorities are. I love it.

Is Christian faith something that book publishers shy away from?

People are wary of explicit Christianity because it may be embarrassing, and because they think it may be propaganda. And not being rude, but some of the things that go by the name of Christian art are not very good. Some of the attempts to create parallel worlds of especially Christian music or entertainment seem to settle for a world that’s too small. Then people outside of it go: “No, we don’t want that. It’s too little.”

I don’t know how you get out of that bind. If you’re not white, Christianity is much more easily accepted as part of your cultural history and the package of things which it’s OK for you to care about. It’s partly to do with the cultural volume that Black British Christianity has, compared to my own dear Church of England – which is not very cool as an institution, I have to say! But we have got lovely flower arranging…

Every now and again, a book like The Shack (Hodder Windblown) breaks through into the mainstream. How do we do more of that?

I’m not sure it’s a repeatable formula. At the top end of literary fiction, Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead (Virago) comes out and suddenly a great many people find themselves curious about the world of faithful feeling that’s in it. But I haven’t got a master plan that is any more than: write good books, one at a time.

Is it challenging to create great art that stands up in the mainstream, but that also reflects faith honestly, thoughtfully…

And fearlessly! Let’s have that one as well, because part of it is not being afraid of public reaction. I got well known first, before I came out as a Christian so, in some ways, I did it the cowardly way round. But also fearless in the sense of not being afraid of difficult subject matter, and not behaving as if we are restricted to some quiet, good-mannered little theme park of human emotions.

There’s something about not being afraid, timid or limited, but also never settling for propaganda or sentiment; always making things that we think are true. We have the assurance that, no matter how uncomfortable it gets, we have a God of truth, so it doesn’t really matter if we are uncomfortable.

We should behave in line with what we believe, which is that all of human life is open for intelligent and wonderful Christian artistry. The Renaissance is full of artists who would agree with you about that. We need to get some of our cultural confidence back.

What would you say to Christians who think we should spend more time reading the Bible – or perhaps Christian nonfiction – but who don’t put the same value in fiction?

I have to break it to them that the Bible is full of stories! There is a difference between saying: “The Bible contains everything necessary for salvation” and saying that you shouldn’t do anything else. It doesn’t mean you can’t enrich your life and faith by rejoicing in everything that human creativity can add to that.

Every generation has the responsibility of building a new bridge between scripture and people’s everyday experience, and storytelling is part of that. Reimagining that is part of the permanent duty of being a Christian. Just going: “Sorry, I wish to be alone with the New International Version” is not going to do it.

“Always be prepared to give…[a] reason for the hope that you have”, as it says in the Bible [1 Peter 3:15]…

Exactly. Even if it might involve a bit of swearing [laughs].

You said we should rejoice in everything that human creativity can add, but there must be limits to that, surely?

There are some kinds of imagining and enjoying which are not good for us, but they aren’t the generous kind, or the kind which is fearlessly curious about other people’s lives. They tend to be enormously monotonous; the things that offer pleasures cheaper, simpler and cruder than in real life, or that offer lying substitutes for realism.

There is nothing to fear in describing anything, so long as the commitment to truthfulness is there. But it is possible to twist anything for a satisfaction which is a kind of escape from reality – and now we’re back at the beginning of the conversation. That’s the wrong kind of escape. We wish to escape from the jail cells of our limitations and our sins; we do not wish to escape from reality. Reality is the good stuff.

To hear the full interview listen to Premier Christian Radio at 8pm on Saturday 18 November or download ‘The Profile’ podcast at premier.plus

Francis Spufford’s latest book, Cahokia Jazz is out now

All photos (c) Samuel John Butt

No comments yet