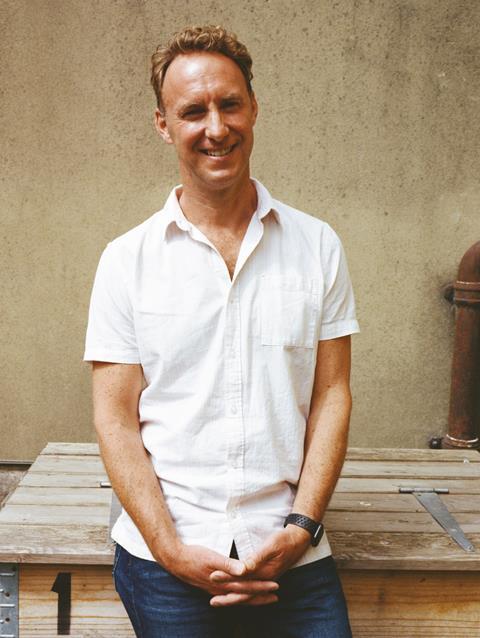

As Archie Coates leaves Brighton to head up Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB), he tells Megan Cornwell about his plans for the largest Anglican church in England

We’re in the middle of a heatwave when I arrive in Brighton to meet Rev Archie Coates. The air hangs uncomfortably close as flamboyant Brightonians saunter in and out of the vintage shops and vegan cafés crammed along Trafalgar Street. A Dickensian-looking man in a grubby top hat slouches by the side of the road, speaking to an invisible someone. Under his discarded coat lie an unlikely assortment of trinkets hawked to passers-by.

Before I reach the confluence of Trafalgar Street and York Place, the top of St Peter’s appears, stretching into the sky like arms held high in a hallelujah. The church’s late gothic facade is currently entombed in a metal brace of scaffolding, a visual reminder that while this patient may have been revived, she requires ongoing support.

Referred to unofficially as ‘Brighton’s cathedral’, the 200-year-old Anglican building was threatened with de-consecration in 2007 due to a dwindling congregation and spiralling costs. Enter Rev Coates, and his team of 30 from Holy Trinity Brompton (HTB), who were sent to plant the evangelical style of Christianity that characterises the growing HTB network.

Pre-Covid, the community swelled to roughly 1,000 believers who met across five sites and who planted out of their plenty into the parishes nearby.

Under Coates’ watch, St Peter’s has set up homeless outreach projects, courses on mental health, and mentoring for disadvantaged young people. By all accounts, it is a Church of England success story.

Over a decade into leading the church in the heart of Britain’s unofficial LGBT capital, the 52-year-old, his wife, Sam, along with two of their four children, are boomeranging back to Knightsbridge where Coates will take over as HTB’s new vicar this month.

In many ways, he’s exactly who you’d expect to succeed Nicky Gumbel in the heart of London’s wealthiest borough: a posh priest with a pristine report card. There are no skeletons in this cassock (not that he usually wears one).

Like Gumbel before him, Coates grew up in London, was privately educated and an Oxbridge graduate. After a “miserable” year in sales – doing “what I thought I wanted to do” – Coates received an invitation from a vicar in Pimlico to run Alpha at his church.

He flourished there and went on to do a theology degree at Wycliffe Hall, later becoming associate vicar at HTB, serving for six years alongside Gumbel. In 2009 Coates moved to Brighton, with Gumbel’s son, Jonny, to take on St Peter’s.

His return to the capital and the birthplace of the Alpha course may seem inevitable, but Coates is clear: it was God, not Gumbel, who called him back. Having strong ties with its incumbent probably didn’t hurt his chances of scooping the top job, but a career Christian Coates is not.

When I ask whether he could see himself as archbishop one day – a not entirely obscene idea given Most Rev Justin Welby’s past links to HTB – he looks genuinely surprised. “I certainly don’t think in terms of career,” he says, eyes shifting towards the ground, looking uncomfortable at the thought.

For Coates it’s not about a position or platform – it has always been about love and service – and reaching those millions of city dwellers in need of a saviour.

Humility, writ large through Coates’ posture – hands demurely in his lap, head bowed slightly as he talks – is perhaps a result of understanding profoundly that without God he can do very little.

It was a lesson he learned young, during a painful season at boarding school – the memory of which still acts as an emotional trigger today. An environment that threatened to overwhelm him as a child pushed him to lean into the firm foundation on which he stands today.

This is why, despite now being responsible for the CofE’s flagship and 3,000-strong evangelical community, Coates prefers to think of himself simply as the vicar of a local church who is deeply and undeservedly loved by God.

Archie, you’re on the cusp of taking over from Nicky Gumbel at Holy Trinity Brompton, the UK’s largest, and some would say, most influential Anglican church. How does it feel?

Well, it feels exciting and daunting. What’s that phrase? Standing on the shoulders of giants. Because, obviously, Nicky, but before that, Sandy Millar – who actually I trained under. So you think: Goodness. You feel this amazing honour, and quite a responsibility. It’s a little bit daunting. But we feel called, my wife and I.

What direction are you going to be taking HTB in? How much are you going to be changing?

I think I need some time to look at everything and get my feet under the table. But broadly the vision stays the same: to play our part in the evangelisation of the nation, the revitalisation of the Church and the transformation of society.

And actually that is what we’ve been doing in Brighton these last 13 years. So I think it’s continuity…but also just trying to listen to the Lord for the next season as well, I guess.

What is God saying to you for this next season?

Well…I…in some ways I’m hesitating, because I don’t want to presume before I’ve properly had a bit of time at HTB. But I think that the priorities are, and always will be, for me, around evangelism: proclaiming the good news and care for the poor.

That strikes me as pretty central. I suppose one thing God’s been speaking to me about is London. I was brought up in London, and I have a huge heart for London, which is, of course, a massive, diverse city.

And many of the churches that we’ve planted from HTB over the years – when the leaders talk about being sent out by HTB, they always talk about the vision that God’s given them for their city – be it Brighton, or Plymouth or Bournemouth or Preston or Wrexham.

They don’t talk so much about the church they’re going to. They talk about the city that God is calling them to. And HTB’s city is London, and so I think there’s something about having a vision for London. And one of the things that probably excites me most about that is the diversity of London. It’s increasingly represented now at HTB itself. I think that’s amazing.

It’s interesting you talk about diversity, because the leaders of HTB have traditionally come from quite privileged backgrounds. What does that look like, then, as somebody leading a church full of diverse people, when you are probably in the top stratum of privilege, in terms of what you’ve come from?

Yeah, I was really aware of that. I think everybody was, actually, at my appointment. I don’t know whether there was a kind of rolling of the eyes: Oh here we go. Here’s another middle-aged, middle-class white male. I mean, I am who I am, and I feel called, and I think – I hope – the church feel that I felt called which is why I was appointed.

Maybe the extra awareness could help me in some ways, because I feel like I am coming from a little way back and I’ll need to really have that antennae on.

What Nicky has done in the last few years is amazing, because it’s not diversity simply in terms of representation, it’s diversity in leadership – that’s the critical thing. And we’re not there yet. I feel that’s on me, actually.

It’s one thing to onboard people into leadership who represent diversity, but how do you train and release and sustain that? I think that’s the bit to come.

Is that something you’ve learned while you’ve been here at St Peter’s?

I confess that probably, like others, the spring of 2020 and the George Floyd murder was a real wake-up call. It was like holding a mirror up to myself and to my way of leading and church.

I think some of my approach or training had been: when you [look for] leaders you’re looking for character, competency and chemistry.

I realised that the chemistry I’d gone for was, if I’m honest: people like me. And then someone told me that actually when you do chemistry at school, you often put two things together that are very different to produce a chemical reaction much more wonderful. I feel like I’m learning fast – and need to learn a lot faster.

For example, we have a churchwarden here at St Peter’s who’s Nigerian by background. And I just noticed the richness of the conversations that we have. The way that we led the church together over the last two years has been quite different – beautiful, but also far more effective. And so, primarily, I think it’s listening to people – but it has got to be a bit more than listening. It’s sort of listening into action.

I’ve got people in my life who will talk to me and say: “You know, it’s not good enough, Archie.” But also to actually help me. Educate me, push me, prod me, encourage me.

Some more cynical people might say that moving to HTB is a good career move. I’m thinking of some of the very high-profile Anglicans that are connected with HTB – the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, for example. Do you see your ministry going in that direction?

Oh, no. Not at all. I think it’s the last thing I’d like to…I like leading a local church. I think people who do all the wider stuff are amazing, but it’s not my thing, particularly. So no. I certainly don’t think in terms of career, either.

We love people and the local church and what I really love is releasing potential in people. And I can’t think of a better way to do it than by being a vicar of a local church. So that’s really our heart.

We’ve seen in recent times some pretty large-scale church scandals. How do you guard against some of the temptations that come with greater platform and greater power?

I think firstly, an awareness of those temptations [is important], and particularly around power.

I’ve actually just finished reading a book called Subversive Witness [by Dominique DuBois Gilliard]. And it talks about the biblical characters who have power and leverage it to bring up those who are without power. And I think that’s one of the roles of power; in other words, power is not for oneself. It’s to be very gently and carefully handled in order to bring up others.

I think there’s something about being aware that there is a power dynamic; you can’t help it. But how are you going to use it, not abuse it? Serious reality checks [are needed] all the way through. And make sure you don’t get isolated from people speaking truth.

Also I think there’s the thin end of the wedge: something starts quite innocuously, and the pattern or the trend of that can do bad things. I’m blessed with a wife who keeps me very down to earth, and teenagers who also do – and good friends who laugh at me and to whom I’m Archie, and nobody else. Making sure I’m with them lots will help.

You’re about to step up and lead a congregation of 3,000. You must have quite a lot of courage and get-up-and-go to do a job like that?

I’m not afraid of hard work, perseverance and persistence – I rather enjoy those things. But hard work ain’t gonna do it in the end. Prayer and fasting will. In the end it’s God’s work. If it’s all down to me then that’s a pressure I can’t bear.

If it’s not down to me, then funnily enough that makes one more courageous and more fearless. Because you think: Well, I’ve got nothing to lose. I’m still a child loved by God, he still died and rose for me. I might as well take a swipe at something and have a go.

A lot of Christians are wondering what direction the Church of England is going in, specifically around sexuality. We know that the Church of Scotland is allowing same-sex marriages, and the Church in Wales is blessing same-sex unions. Where do you stand on that debate?

You’re right. It’s going to come to the Church of England. I think it’s slated for Synod in the next…probably 2023. I think the House of Bishops are talking about it quite soon. I don’t know where that will go.

There’s a number of issues, obviously – there’s scripture and trying to work out the truth, there’s unity, which feels important. So I think there’s different ways of looking at it. Sometimes people ask me: “What’s St Peter’s view on it?” (They really want me to say what Archie’s view is.) And I generally say: “Look, St Peter’s is full of a whole kaleidoscope of people, and I’m really glad that we are. I can give my view…but what I prefer to say is: actually, I’m not going to say my own view, because…I want people to be able to be here and find a unity in holding different views.’”

The trouble is, just because of my role, my whisper is a shout. And I think what it does is actually narrow the debate and it narrows people’s sense of unity and working with each other – and wrestling with it for themselves. So pastorally, that’s what I’ve done so far.

What I’ve noticed – and this is going to be a challenge for me – is that when I said that three or five years ago regularly to people, it was perceived as: “Oh, that’s a courageous thing, Archie, that you’re not going to be drawn on it.” (Some people call it sitting on the fence. I don’t think it is that, but…yeah…I understand that.) What I’ve noticed now for that same answer (which is why I think it will be a challenge) is that it’s now perceived as a weakness.

You know: “Archie, you are very assured about some other things, doctrinally, why won’t you…?” It’s beginning to be regarded as bad behaviour, pastorally. You know: “Ambiguity is unkind, lack of clarity is unkind.” So that’s going to be a wrestle for me as I move to HTB.

So when you talk about ambiguity, is that an ambiguity in a sense that you don’t know what you think about this particular issue?

No. I have at the moment a clear understanding of what I think – which I think is always needing to be challenged and wrestled with. But I do. And, as you can imagine, I have talked to lots of people over the years and read lots of things and weighed and yeah…so I do. It’s not an ambiguity in that way.

Take a church like St Peter’s. You either pronounce from the platform a whole bunch of things: this is our view on this, this and this – in which case you produce a kind of unity. But I think there’s a more beautiful unity that happens here, because I know we’ve got lots of people who have lots of different views, not only on sexuality, but there’s Brexit, there’s views about the pandemic.

And what I love is a whole bunch of people who’ve decided that Jesus Christ is Lord, Jesus has risen from the dead, and we’re going to unite around [that]. And then we’re going to continue to discuss and talk about these things. It’s harder in a way, but it’s more beautiful.

Some Christians are concerned that orthodox traditional teaching around marriage is not being defended. Do you think there is an issue with being quiet about it, when there are very strong groups within the Church taking it in a certain direction?

I do. I take my responsibility as a pastor very seriously. And my job is to pastor my flock, so I think it’s really important to be at the very least putting into their hands the things that they ought to be looking up and weighing. Rather than telling them, I want to help them.

So I do think it’s really important that people speak up. And they will do, I think…in every direction. I just, as you can tell, have a hesitation about my own voice in it because there’s lots at stake.

There’s biblical truth and there’s unity, there’s mission, there’s all sorts. You’ll need to come back [to me] in six months or a year. I don’t know whether I’ll think differently, but what I may do is think differently about speaking on it. But that’s probably where I’ve got to so far.

And as I say, Megan, it has been one of the most difficult, painful things in Brighton. And I don’t think I’ve always done it very well. There’s a particular generation – in fact, my children are almost in this generation – that [for them] it’s not just same-sex marriage, it’s the whole thing around gender and identity and everything. And as a pastor, that needs to be pastored.

And just how one navigates that (not navigate as to escape through the fire), but to genuinely help people, that’s where I feel passionately. And I don’t feel like I’ve always been able to do that. And sometimes what has happened is people have walked away. So I feel it keenly, how I wrestle with that.

Tell us a bit about who you were before you were a vicar?

I was one of four children brought up in Bath. My father was a head teacher. We moved to central London when I was 13. I went to a boarding school – one called Marlborough in Wiltshire. I had a faith from an early age, but like anybody who has grown up with the faith, you don’t want to do it just because your parents did.

I feel bad saying this, because it was an incredibly privileged upbringing, but I was very, very homesick when I went to boarding school. I mean, desperately so. To the extent that the school wondered whether I could cope, or whether I shouldn’t be sent back home.

It was rather surprising to me – I didn’t expect to have that sensitivity. And it lasted for a really long time…it was throughout my whole first year, and even a little bit beyond. And what it did was it made me rely on God and my faith. I had an older brother who was a year above me, and he was so kind to me.

So the combination of him and the Lord. That’s where I found my faith.

I can see that you’re getting emotional even thinking about it. What were you struggling with so much and in what ways was the Lord gracious to you?

I had a very, very loving home. And it’s not to say that the school wasn’t wonderful, but you feel exposed. I think the word I would use is ‘protection’. You either protect yourself through building up an image of yourself, or by being good at something, or impressive, but I found that the Lord was my protector. And I think I learned to rely on him.

I was a shy teenager and what I noticed was God gave me confidence. For some teenagers – and there’s nothing wrong with this – it comes through being good at something; it builds your self-esteem. But my sense of self-esteem and confidence, and I would say identity, was driven into me by that year of being 13/14 years old.

So really what you’re saying is: the man that you are today – full of confidence, able to stand up in front of thousands and speak on a stage, leading a huge church – all of that came through that crucible year of difficulty and struggle, and having to really rely on God?

I think so. I discovered that I’m loved – loved by him. It’s a confidence that comes from him loving me unconditionally, rather than a confidence from doing something well. Otherwise, I couldn’t cope, it’d be just too much of a roller coaster.

Because what if the church doesn’t work? What if HTB shrinks? It might do. You have to find some way of feeling called and confident in the Lord. You have to put some separation between who you are in God and what you do for God.

No comments yet