Mars and Flake, Twix and Galaxy, KitKat, Milky Way and Aero. They are like the seven deadly sins in churches up and down the land each spring. Have you ever thought how much Cadbury’s must hate Lent? It’s no wonder Easter positively wallows in chocolate eggs after all that self-denial.

The middle weeks of Lent are always a bit of a low point. Whether you gave up Facebook, Marmite, Jeremy Kyle or one of the above chocolate temptations for the six-week run-up to Easter, the chances are that by now you sincerely want them back in your life. Especially if giving them up way back on Ash Wednesday was a heat of the moment thing, spiritually speaking.

Asking people how they’re doing with Lent several weeks in feels the same as asking them at the end of January, ‘How are those new year’s resolutions coming along?’ Of course, as we’re always told, Lent isn’t just about giving things up. It’s also about taking things up: getting out of bed extra early to pray, being nice to your ghastly boss, reading the Book of Leviticus, forgoing the joy of cutting up other drivers at the lights.

Lent becomes the blessed bloodbath it’s meant to be

But actually, giving things up is still where Lent cuts the deepest. It’s only when we seriously try saying no to ‘brother body’, as St Francis endearingly called it, that Lent becomes the blessed bloodbath it’s meant to be.

Lent could be easier if people were more familiar with the small print. I’ve often found that not everyone knows you can have Sundays off, for example. The reason being that every Sunday is a celebration of the resurrection – and is therefore an opportunity to praise the Lord by getting alone with a party-sized pack of Maltesers. Some churches, such as the Ethiopian Orthodox, also take Saturdays off to make a weekend of it, but then they have to compensate by having a colossal eight-week Lent to get in the full 40 days of fasting.

Last year year, noted believer Anne Widdecombe announced her Lenten cutbacks (which surely takes points off her Purgatory loyalty card for the sin of boasting). "As usual," she thundered, "it will be everything except fizzy water to drink: no alcohol, tea, coffee, cola or fruit juice."

The items people drop for Lent are quite individual and sometimes eccentric.

Her list of privations made me realise that the items people drop for Lent are quite individual and sometimes eccentric. Fizzy water might be exempt from Anne Widdecombe’s list, but why is that? It’s not as if Jesus went into the wilderness with a bottle of San Pellegrino.

I checked back on how our Christian forebears tackled things in Victorian times by reading some of the booklets they published. I was rather thrilled to discover they invented the Lent book, with its mixture of pop theology and sober advice on what to give up and what to take up. Their preoccupations are a world away from KitKat and fizzy water.

"Can it be fitting that any of the Lord’s disciples should be marrying or giving in marriage whilst He is lonely and fasting in the wilderness?" asked Charles Kennaway in his twopenny booklet of 1849, How Lent May be Kept by Rich and Poor. The Rev. William Kip agreed and noted that the principle extended to celebrating birthdays, which were "inappropriate to a season which should be devoted to deep humiliation and mourning."

Meanwhile, Bishop Jeremy Taylor, writing about almsgiving, advised that "many things might be spared; some superfluous servants, some idle meetings, some unnecessary and imprudent feasts, some garments too costly, some unnecessary law-suits, some vain journeys."

It reveals the mundane habits and inner demons which assail modern Westerners.

A Catholic bulletin board reveals the things people fast from in 2014: selfies, French fries, playing basketball, saying OMG, coffee ‘which is the fuel of my life’, McDonalds, sex, rock’n’roll, ‘animal based products including honey’, lottery scratch cards, Justin Bieber, anger, ‘listening to music (excluding Gospel)’, pizza, online shopping, my bed – ‘I sleep on the floor every night’, lying, cursing and Poker websites. It’s a highly specific list which shows how the temper of Lent has changed since Victorian times, and also reveals the mundane habits and inner demons which assail modern Westerners.

Lent is just 40 days out of the year for most of us, but for others it has been and is a chosen way of life, with eccentric saints living on top of poles, monks and nuns who take on ‘poverty, chastity and obedience’, and believers who forsake home and comfort to live and work in the world’s most needy places. The condition of many people living on earth today can be described as Lent without Easter. It’s for them that we should have more Lent in our lives, the whole year round.

This extract has been from Jumble Sales of the Apocalypse by Simon Jenkins (SPCK)

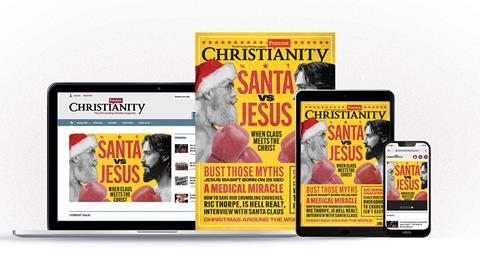

Click here to request a free copy of Premier Christianity magazine