Early Christians found the crucifixion so shocking that they didn’t make an image of it for 200 years. But in the centuries since, how the Church portrays the cross has changed many times. Historian Martyn Whittock looks at what's happened

Early Christians were acutely aware of the controversial nature of their belief that God’s son, the Christ, had died by crucifixion - a method designed solely to shame and humiliate.

In 1 Corinthians 1:23-24, Paul reiterated how contentious this belief was: “We proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those who are the called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God.” (NRSV).

Centuries later and our familiarity with this event – combined with the Protestant tendency to portray an empty cross rather than a crucifix – can sometimes blunt the jagged edge of this belief. But taking a look at how the crucifixion has been depicted over the past 2000 years will help remind us of its raw and controversial power.

Shocking

The earliest surviving picture of the crucifixion, dated from the year 200, from the Palatine Hill, Rome, was not made by Christians and was clearly designed to offend.

A figure raises a hand in worship to a donkey-headed person naked on a cross. Below the crude sketch and scratched in Greek is written: “Alexamenos worships his God.” We do not know who scratched it into the wall, or who Alexamenos was, but we do know that the crucifixion of Jesus was shocking. And while Christians were quick to write about it, for about 200 years they were slow to depict it. The image was so raw.

Serene Jesus

When the Roman Empire began to convert to Christianity, from the 4th Century onwards, depictions of the crucifixion became more common. And once it was banned as a form of capital punishment, it became more acceptable to depict it.

These early images often lacked the violence of the real event, showing Jesus ‘reigning from the cross’. This was the official – serene – image of the crucified Jesus that would inform people’s imagination until well into the Middle Ages. In the most elaborate examples, jewelled crosses (the “crux gemmata”) proclaimed the majesty of Christ’s sacrifice. But there was little suffering shown in these magnificent objects of devotion.

In our image

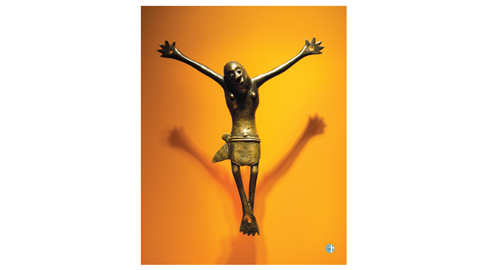

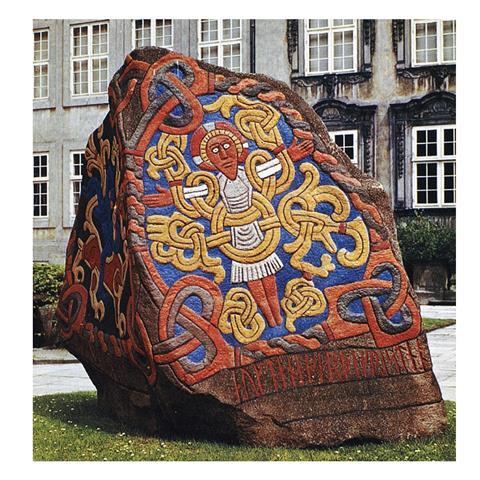

As Christianity expanded beyond its Mediterranean heartland, other cultures began to depict the crucifixion in ways which resonated with their own ethnicity.

In the Viking North, the crucified Christ wears trousers like any Norse man. At Jelling, in Denmark, an image of a bound (not nailed) Jesus was carved on a runestone using Norse artistic traditions. In sub-Saharan Africa, a clearly African Christ is nailed to the cross. Across Asia and the Americas, people depicted the crucified Jesus in their own image.

Later, from the 13th Century onwards, changes began to take place within the European artistic tradition and there was a rediscovery of the suffering of Christ. Images of Jesus reigning serenely from the cross gave way to ones portraying the pain and brokenness. As the Black Death swept across Europe in the 14th Century, this accelerated. In some pictures, Jesus was even made to appear as a plague victim, as if to emphasise the connection between the 1st Century crucifixion and people’s experiences of pain and suffering during the pandemic.

The empty cross

During the Reformation, many Protestants abandoned the crucifix image and replaced it with the empty cross. A reaction against the medieval veneration of crucifixes, it also meant that for many Protestants, the visual portrayal of Christ’s suffering was no longer a central part of their Christian experience.

While Christians were quick to write about the crucifixion, they were slow to depict it. The image was so raw

Today, many modern portrayals of the crucifixion, often in film (see Mel Gibson's The Passion of the Christ), have chosen to make clear the bloody and shocking nature of Christ's death. Nevertheless, for most Protestants, the empty cross remains the dominant image within churches. At the same time, there has been a necessary correction of the over-dominance of images of ‘White Jesus’ that proliferated with colonisation.

Modern artistic works are now more widely representing those that created them, and seem more willing to explore the shocking violence of crucifixion.

These modern depictions once again remind us that Jesus identifies with the whole of humanity. And that, in the violence and humiliation of the cross, the depth of God’s love and the cost of salvation is beautifully and wonderfully revealed.