Can an ordinary communion wafer miraculously transform into tissue from the heart of Jesus? As the world’s first millennial saint, Carlo Acutis, is canonised, Tony Wilson investigates one of the Eucharistic miracles that he so carefully catalogued before he died

A seemingly ordinary boy is set to become the first millennial saint of the Roman Catholic Church in a celebration at Saint Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican this month.

Carlo Acutis was born in England to Italian parents at the dawn of the internet age in 1991. Investigating his life has led me to an international story featuring contested miraculous events in Buenos Aires, a bishop who would become pope and my own conversation with an expert lawyer who may have uncovered concrete evidence for Christ’s divinity.

The faith of a teenager

Acutis was incredibly brave in the face of his death, aged just 15. Having been diagnosed with leukaemia, he spent time in intensive care on a ventilator. His last words to his mother were: “Mum, don’t be afraid. Since Jesus became a man, death has become the passage towards life, and we don’t need to flee it. Let us prepare ourselves to experience something extraordinary in the eternal life.”

Carlo’s parish priest described the boy as “exceptionally transparent” and his peers regarded him as kind rather than pious. Accounts of his life show he was unfailingly on the side of the poor and the oppressed, with a deep concern for the wellbeing of others. But it is the website he designed and curated in the two years before his death which really caught the public’s imagination.

Would you apply the same critical scepticism if a person claimed a miracle at a healing service in your church?

That’s because this website records every claimed ‘Eucharistic miracle’ dating as far back as the eighth century.

The phenomenon of miraculous events related to bread and wine consecrated in the Eucharist, little known even in Christian circles, has been documented for more than 1,300 years and total at least 139 separate events. The term ‘Eucharistic miracles’ encompasses a range of phenomena in which the bread or the wine transform into substances which are claimed to be real flesh and blood.

One of the most recent incidents took place in Buenos Aires in the 1990s. It grabbed my attention because it was recent enough to have been investigated using modern scientific techniques.

The Buenos Aires miracle

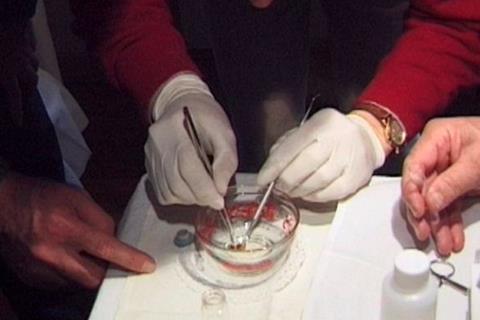

At the end of an ordinary Mass in Santa Maria Church in August 1996, a parish member found a discarded communion wafer on the floor, covered in dust. Because Catholics believe that Jesus is fully present in each consecrated wafer, there are strict guidelines on what to do with those that are not consumed. She presented it to the priest, Father Alejandro Pezet, who correctly and reverently placed it in water and locked it away to dissolve.

When Fr Alejandro returned to dispose of the water a few days later, he was shocked to find the wafer intact. What’s more, a blood-coloured spot had appeared on the surface. Over the following days, the stain grew into a flesh-like substance. Fr Alejandro reported the strange event to the diocese which, at the time, was under the leadership of Archbishop Jorge Bergoglio – who would later go on to become Pope Francis. Bergoglio commissioned professional photographs of the wafer before safely storing it in a locked tabernacle.

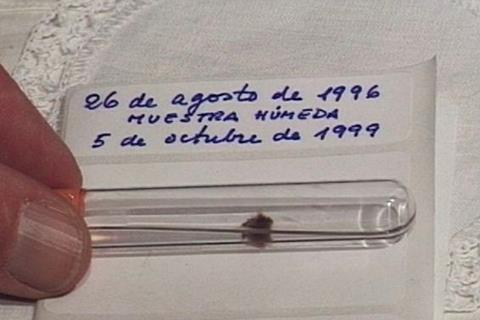

For the next three years, the substance was stored in a glass tube containing distilled water. In 1999, Archbishop Bergoglio requested Dr Ricardo Gomez to undertake a scientific investigation. Gomez, who was then an atheist but would later go on to convert, agreed to take the case on after being intrigued by an earlier Eucharistic miracle in the diocese in which AB blood antigens were found to have spontaneously arisen in a consecrated wafer.

Samples taken from four previous Eucharistic miracles – and from the Turin Shroud (the claimed burial cloth of Christ) – all showed traces of the same rare blood type. If these five blood samples – spread across the world – had come from five different people, the chances of them all having an AB blood type is less than one in 3 million. Does this suggest a single donor?

Some Christian commentators were quick to point out that people with AB blood are known as universal plasma donors, as it is safe to give to anyone, regardless of the recipient’s blood type. How fitting to suppose that the blood of Jesus, shed once and for all, contains plasma suitable for the entire world to receive.

Yet some doubted. Scientists, including Catholics such as Dr Kelly Kearse, demonstrated that certain types of fungus spores, quite conceivably present in the dust of a church floor, could grow on the surface of a discarded communion wafer. These red spots would also contain AB type antigens that would respond to tests exactly like the rare blood group.

Gomez, choosing to ignore blood-type sampling, focused instead on testing the DNA of the Buenos Aires red substance. In the first round of experiments, human DNA was found, but the sample did not yield a full genetic sequence. Sceptics argued that the original communion wafer had passed through several hands before being isolated and so the presence of human DNA was not surprising.

Blind testing

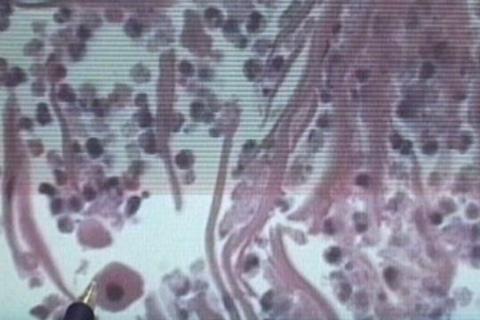

At this point, Dr Gomez enlisted the help of Australian lawyer Ron Tesoriero, who had experience of leading enquiries of this kind. They took the sample to a forensic laboratory in San Francisco for blind testing. Here, Dr Robert Lawrence extracted a slice of tissue and fixed it on a slide that was code-stamped 99-441. Lawrence thought that the cells resembled those of human epidermis (skin tissue) but laboratories around the world came to different conclusions. Some reported muscle tissue, possibly from the heart.

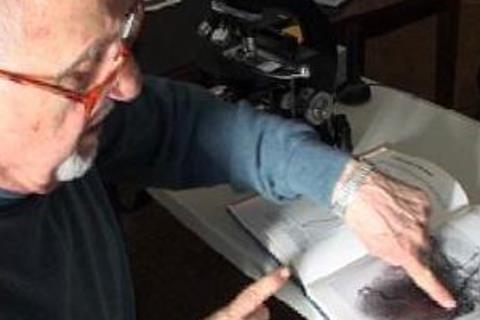

With no consensus emerging, Tesoriero, himself a Catholic, was determined to find out the nature of the mysterious tissue. Comparing the cellular images with textbooks, he concluded that they bore no immediate similarity to normal human tissue. With suggestions that the slide might contain heart cells, Tesoriero found a world expert in Dr Frederick Zugibe, a New York state chief medical examiner. As a Fellow of the College of American Pathologists, the American Academy of Forensic Scientists and the American College of Cardiology, Zugibe could hardly have better credentials to examine the tissue.

To find a naturalistic explanation, I’d have to accept that someone extracted heart tissue from a recently deceased trauma victim to carry out a bait-and-switch

Tesoriero was determined that Zugibe should investigate the tissue without any knowledge of its history, but he also wanted to make a live recording of the meeting without creating suspicion. He presented himself as a lawyer requesting an unbiased opinion, plausibly acting for a legal jurisdiction in an undisclosed case.

The video, which has since been viewed more than 150,000 times on YouTube, shows Zugibe giving a live commentary as he looks down his microscope and examines the tissue. With the confident authority of a man at the top of his field, he articulately recounts what is before his eyes; heart tissue showing evidence of the type of trauma one would expect from someone beaten across the chest. This aligns closely with gospel accounts that refer to Roman scourging – which included whipping and beating (Matthew 27:26; Mark 15:15; John 19:1).

Furthermore, he explained that the presence of white blood cells in the heart tissue pointed to the person still being alive when the trauma was inflicted, quite likely some time before death occurred. These white blood cells dissolve within hours of death, he added, concluding that the sample must have been extracted and fixed on the slide immediately thereafter.

When Zugibe learns the sample was in ordinary water for three years, he is not able to provide a scientific explanation for this. When told that the sample came from a Eucharistic wafer, words fail him completely.

Sceptics have suggested that the flesh-like substance could be a naturally occurring fungal growth, as posited by Dr Kearse. But even if that were so, is it plausible to suppose that a leading heart pathologist would confuse fungal cells for human heart tissue? Others have criticised the Church for not having more robust systems to ensure an uninterrupted chain of custody for samples of this kind. Although, in the busy life of an average parish, it is hard to imagine how this degree of clinical certainty could be expected.

New evidence

When I called Tesorieroto discuss his findings, he offered me a tantalising piece of new evidence. In 2016, following advances in DNA testing, he submitted a newly extracted piece of the substance for blind testing at Menarini Silicon Biosystems in Bologna, Italy. Their groundbreaking technology allowed them to extract DNA from the single white blood cells that were still preserved, against all scientific explanations.

The precision of their instruments allowed DNA to be extracted from the cell nucleus which yields a complete genetic code derived from both the mother and father of the donor. Mitochondrial DNA, coming only from the mother, was taken from elsewhere in the cell.

In a surprise result, data from the nuclear DNA failed to provide a full human genetic code, yet a perfect maternal sequence was obtained from the mitochondrial DNA.

Could this person really have a human mother but no father? Or did the sequencing of the nuclear DNA fail for some reason? Could we be glimpsing evidence of the human and divine parentage of Jesus?

Christians believe that Jesus is fully man and fully divine in a mystery that goes beyond our comprehension and measurement. I’m not sure what it would even mean for a human to have no complete DNA sequence.

How fitting to suppose that the blood of Jesus, shed once and for all, contains plasma suitable for the entire world to receive

I challenged Tesoriero by asking if he has matched the maternal DNA with databases to show the ethnic origins of the mother. If he could show this sample came from a Middle Eastern woman with Jewish origins, we would all have pause for thought. But Tesoriero has his eye on a bigger and more impressive goal. He is currently lobbying the Vatican to allow mitochondrial DNA to be extracted from the Turin Shroud – he is confident it will be a perfect maternal match with the Buenos Aires sample.

For now, however, the evidence remains open enough for anyone to believe – or reject – the claim in good conscience. Has God himself allowed a cloud of uncertainty to exist around every claimed miracle? Nothing in the course of human history has prevented God from emblazoning “Jesus is Lord” across the sky, but he has good and necessary reasons for not doing this. The consequence of giving incontrovertible evidence that the Christian faith is true would compel the whole world to believe. God’s self-revelation through history is that of a gently wooing lover, respecting the rights of those who choose to reject him. The imbalance of power between the creator and the creature means God must remain veiled to fully respect our human autonomy.

Confirmation bias

Our willingness to pick over a story and give credence to some claims while doubting others may, ultimately, tell us more about ourselves than the strength of the evidence itself. An atheist committed to materialism wishes to explain everything in naturalistic terms and is disposed to reject the miracle. And there is enough evidence for them to do so.

Conversely, you may approach this as a Christian who is uncomfortable with the Catholic idea that Jesus is really present in the Eucharist – and choose to weigh the facts accordingly. Does your personal belief around what happens at the Lord’s Supper cause you to doubt these miraculous accounts? Would you apply the same critical scepticism if a person claimed a miracle at a healing service in your church?

Psychologists call this confirmation bias; the desire to have our beliefs confirmed by the evidence. Regardless of how open-minded we think we are, we often subconsciously prioritise data that supports what we already believe to be true.

Characteristically cautious, the Roman Catholic Church investigates miracle claims with care. A reported healing miracle is scrutinised for many years by independent doctors, allowing sufficient time to pass to discount natural causes such as remission before a genuine miracle is declared.

The Vatican has followed the Buenos Aires miracle with great interest and has, so far, chosen to allow each person to determine how to assess the evidence rather than binding all the faithful to accept it as genuine. The Turin Shroud is similarly treated as an object worthy of contemplation rather than receiving the stamp of authenticity by the Church.

To the faithful Catholic, every Eucharist is a miracle in which Jesus humbles himself to become fully present and unite himself with our humanity. Some regard accounts such as Buenos Aires as an unnecessary sideshow.

What do I think? By faith, I am a Christian. By training, I am a scientist. And I’m minded to accept that a miracle took place in Buenos Aires. To find a naturalistic explanation, I’d have to accept that someone extracted heart tissue from a recently deceased trauma victim to carry out a bait-and-switch on the scientific community.

On the balance of probabilities, I’d say this case was more likely true than not. However, I cannot conclude that it goes beyond reasonable doubt and, if I was on a jury, I wouldn’t send someone to prison on evidence like this.

Nonetheless, as we enjoy the celebration of a short life well-lived, let us give thanks for Carlo Acutis, a young man who put his faith in Jesus. He has brought the fascinating accounts of Eucharistic miracles to the world’s attention. Let us pause to take in the possibility they may point us to the God who gave everything for the salvation of us all.

A second opinion

Miracles can be a contentious issue for Christians. Personally, I have no problem with the miraculous – our entire faith depends on the miracle of the resurrection of Jesus Christ! But I do have a problem with the overly vigorous pursuit of miracles that we sometimes find in the Church.

I would be extremely hesitant to suggest that this case is a miracle, let alone a scientificallyproven one. There appear to be too many other possible avenues of explanation left unexplored or unresolved. I cannot rule a miracle out, but I very much cannot rule it in either.

Miracles come in all shapes and forms, not just the flash and bang type that we often crave. There are miracles of healing, of timing, of providence, of personal transformation. We tend to pit miracles against natural law, viewing it as God versus science. Miracles are viewed as God overcoming or dodging the power of science.

However, this is just another way that we mistakenly set up the Church to be at odds with the scientific enterprise. Natural law, which is all that science studies, is simply just how the universe goes about its day job of operating. That our universe exists, that it continues to operate reliably, that natural law itself continues to work is a true miracle itself.

As Christians we believe that God intentionally created, deliberately upholds, and continually loves this universe. What we see as ‘natural law’ is in fact the moment by moment will of God causing this amazing universe to exist. It is an ongoing, unseen miracle that we have become so used to seeing that we forget that it is there… and instead try to look for God in what we perceive as exceptions to that unseen miracle.

I have no problem with a God who may perform miracles outside the norm of what we expect. But these are and should be the rare exceptions, given to us for specific purposes, to point people closer to God who need it most in a particular moment. They can be a part of a healthy faith but can become unhealthy when an outsized pursuit of them is to the detriment of other aspects of our faith. We are very capable of idolising anything.

We are at our best though when, as Christians, we are resolutely open and expectant to the supernatural, but when we also allow ourselves to see God’s ongoing activity in everything around us. Our faith demands that we are both supernatural and super natural Christians.

Dr Gavin Merrifield is the general secretary of Christians in Scienc

No comments yet