From rape to bullying to murder, the Old Testament contains stories that should shock us. Rosie Dawson speaks to leading theologians in order to find out how Christians should understand them

For those who were studying Theology in the early 1980s, as I was, the publication of Phyllis Trible’s Texts of Terror (Fortress), examining four stories of rape and violence in the Old Testament, was a shock and an awakening. The slim volume quickly became standard reading on the Feminist Theology modules gradually being introduced onto university courses. But outside the world of academics, and through years of churchgoing, I have rarely heard the biblical stories of Hagar, Tamar, an unnamed concubine, or the daughter of Jephthah preached or taught on. All of these stories are about the rape, abandonment, bullying and murder of these women by – or with the connivance of – the men they could have expected to look to for protection. What should we make of them?

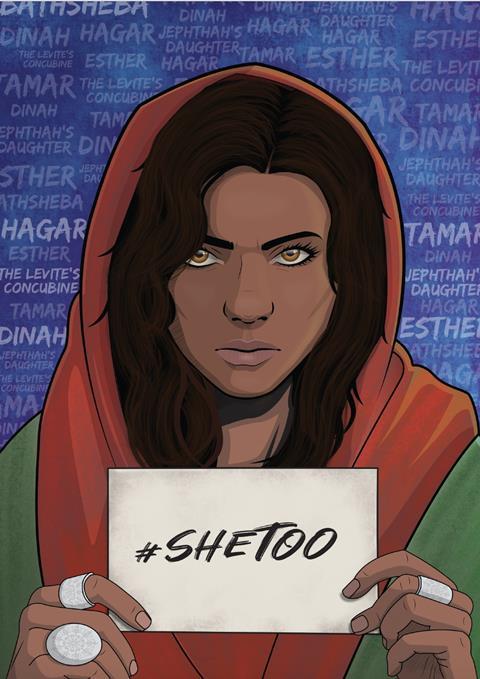

With the #MeToo movement and a daily news diet of stories of sexual abuse within churches, it seemed to me that a podcast revisiting these texts might tap into a wider national and global conversation. And so it proved. Bible Society commissioned me to produce the #SheToo podcast, which examined these four stories. Within a fortnight it had topped the iTunes religion and spirituality podcast charts. I learned via Twitter that it was being used in church discussion groups and on college courses; by Christians for whom the Bible is authoritative, and by others for whom its significance lies not in any divine inspiration but in its abiding cultural influence and power.

THE LEVITE’S CONCUBINE

The story of the Levite’s concubine is told in Judges 19. We read that a Levite had “taken to himself” a concubine who had become angry with him and gone back to her father’s house. He went to fetch her, tarried a while enjoying the company of his father-in-law and set out for home late in the day, which meant they were obliged to seek hospitality on the way. They found it in the home of an old man in Gibeah. While they were relaxing inside, some “wicked men” (v22) from the tribe of Benjamin attacked the house and threatened to rape the Levite. The host was naturally horrified at the idea but the means by which he sought to placate the men was to suggest they rape his own virgin daughter and the Levite’s concubine instead. When the assailants were still not persuaded, the Levite threw his concubine outside. She was gang raped through the night and found dead by her master the next morning “fallen in the doorway of the house, with her hands on the threshold” (v27).

That is not the end of the story. The Levite – denying his responsibility for the crime – decided the destruction of his property (the concubine) by the Benjaminites was an outrage. He cut up her body and sent a part of it to all the tribes of Israel as a way of calling them to a meeting to decide how to take revenge. War ensued. We are told that the Lord gave the battle instructions and “defeated Benjamin before Israel” (Judges 20:35). When the tribes realised that the tribe of Benajmin might eventually die out because there were no wives left for the surviving men, they found the solution in further orgies of killing, and abducted hundreds of suitable virgins to force into marriage. You could argue that the rape of the concubine is clearly condemned in the story. It is not so clear that the rape of hundreds of virgins is similarly condemned. You might think that it is simply presented as a solution to a problem. The text is ambiguous.

I discussed this story with Dr Mary Evans who is a Christian and former vice-principal of the London School of Theology. “I come from a background which sees the Bible as the word of God which has a message for us. But I see it as needing to be interpreted and sometimes we’ve got the interpretative techniques wrong. We need to ask what the text is saying and why it is saying it.”

Dr Evans thinks it’s significant how during the first part of the story, God is absent from the narrative. She believes this is a deliberate omission on the part of the authors. But what do we make of the story later on when God does get involved? “I think even when God is mentioned later on it’s in a way that doesn’t reflect the understanding of God that you get in the covenant texts,” says Evans. “You keep getting this refrain: ‘There was no king in Israel and everyone did what was right in their own eyes.’ It’s as if the writer is drawing your attention to this and saying people weren’t asking what God wanted – that was irrelevant to them.”

The task facing today’s reader, says Evans, is “trying to work out how far the text is saying: ‘This is what God wanted’ and how far it is saying: ‘This is what the people thought God wanted.’ That’s a difficult one. And how you interpret that tends to depend on your own presuppositions.

“I don’t think you can read this story without being horrified,” she adds, “and it seems to me that is what the writer intended. Sometimes people read it as though the Bible supports rape. They say they can’t bear the Bible because it tells these awful stories with the implication that God is allowing or supporting these awful things. In this case that is absolute nonsense. The text is very clear that this is not how it is meant to be.”

Why not leave the story buried in the book of Judges? Should it really be made the stuff of Bible study groups and sermons? “It’s important that we read the story because it’s there. And in our #MeToo society where we recognise abuse and how much it is happening, we must realise that it’s recorded within scripture and it’s clearly presented as not what God intended, and not how the people should live. Scripture tells the story. We should tell it.”

HAGAR

From one story, which, while it is about other things too, is clearly about rape, to another story, which has not been generally recognised as being about rape at all. Hagar is the Egyptian slave of Sarah, Abraham’s wife (Genesis 16). When Sarah is unable to conceive, she suggests to Abraham that he sleeps with Hagar to provide them with an heir.

The director of the Institute for Interdisciplinary Biblical studies at Sheffield University, Dr Katie Edwards, with whom I discussed Hagar’s story, doesn’t come to her reading of the Bible as a Christian. “I’m interested in how the texts work in popular culture and in public debates about marriage, race and class,” she says.

Edwards’ analysis of this text will be shocking and uncomfortable for many. “To me it’s one of the overlooked rape narratives in the Bible,” she argues. “It’s a classic rape narrative.”

THE BIBLE IS THE WORD OF GOD BUT IT NEEDS INTERPRETING AND SOMETIMES WE’VE GOT THAT WRONG

Abraham was the man with whom God established his covenant with his chosen people. If we read this passage in the context of the times, perhaps we shouldn’t understand his actions as rape. But Edwards says she is reading from the point of view of Hagar. Hagar was forced to have sex. What else are we to call it?

“This is a text that isn’t really recognised as being anything to do with sexual violence. That in itself has to be a reason for us to look at it with new eyes,” she says. “You have someone who’s enslaved. She’s not able to give consent. There’s lots of debate around rape in the Hebrew Bible. Rape as a word doesn’t exist, rape as a concept doesn’t exist, but because I am reading this text right now and looking at it in terms of issues we’re facing right now, I think we need to call it out for what it is.”

In calling out Abraham’s behaviour, the role of Sarah cannot be ignored. She was complicit in the rape; indeed, it was her idea. The story tells us about power dynamics between men and women and between women and women in a society where the primary function of women was the ability to produce male children.

Hagar becomes pregnant and Sarah cannot contain her jealousy. She mistreats her slave to the extent that Hagar runs away into the wilderness. The angel of the Lord finds her there, calls her by name (this is significant, no one else in the story does) and tells her to return to her mistress and submit to her. This is a difficult text for Christians to deal with. What do you do if God’s angel tells you to return to your abuser? What does that say about God, who wills it? Some Christian ministers today will still quote from the Bible to counsel victims of domestic violence to go back to abusive husbands. The message that gives is that the victim’s suffering must be endured because there is some higher purpose at work – whether the conversion of a husband or the making of a nation.

“It’s a tricky picture of God,” says Edwards. “On the one hand, he uses her name but at the same time you have a God who suggests that a slave who has been horrendously treated returns to the abusers. So there’s a lot to challenge in the text, but the text does have room for that challenge. In giving us this ambivalent portrayal of God it is allowing us to do that.”

So Hagar returns to Sarah and gives birth to Ishmael. Maybe things aren’t so bad for her for a while, but when Sarah gives birth to her own son some years later Hagar is again driven out into the desert, this time with a child. Without food and water, she fears for the life of Ishmael and God’s angel intervenes, “topping up the supplies,” as Edwards puts it. Then we are told that God is with Ishmael as he grows up in the wilderness. The focus has switched from mother to son. Edwards is troubled by that.

“Where is Hagar in terms of her social status, in terms of the power people have over her now? This might be the place to hear that God was with Hagar and Ishmael or to hear that Hagar was also able to flourish under God’s power, but actually we’re missing at the end of this story anything that might make someone reading for Hagar feel comforted – even a little.”

BIBLICAL STORIES HAVE AN ASTONISHING CONTEMPORARY RESONANCE

Hagar is overlooked both in the text and in our readings of it. Edwards says it’s important that we ask ourselves why. “We’ve overlooked it because it tells us about the people we overlook now. It’s showing us there are still similar patterns in our response to sexual assault against particular groups and communities where we don’t recognise them. That’s why it’s important.”

THINKING AGAIN

There are other stories in the Old Testament which, in the light of our #MeToo moment, make us think again. Did Bathsheba have any choice about whether or not to lie with David? How did I ever think the story of Esther was about a beauty contest rather than about the trafficking and grooming of young girls? For all the distance of thousands of years, biblical stories can have an astonishing contemporary resonance.

What this journey into some of the Bible’s most difficult stories reminded me more than anything was this: the Bible makes for uncomfortable reading. It doesn’t always provide neat answers or fit with the ideas we’d like to have of ourselves or of God. Sometimes you just have to sit and wrestle with that. But how you read the Bible matters. It matters a great deal.

This article was first published as the cover story for the July 2019 issue of Premier Christianity

1 Reader's comment