Christians have a dual responsibility to question conspiracy theories and show compassion to those who believe them, says Jared Stacy

Today’s world is being shaped by lies in terrifying ways. In recent weeks, for example, we have witnessed Vladimir Putin’s disinformation campaign to justify the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

But it’s not just officials in the Kremlin making spurious claims; during the pandemic we’ve also been bombarded by falsehoods. Conspiracies appear in our search results, while scrolling on social media or in conversations with friends and family. What were, at one time, beliefs held by extremists, fringe groups or eccentric uncles – the earth is flat, the moon landings were faked, I know who really shot JFK – have now filtered into the mainstream consciousness, aided by technology that makes sharing content easier. In a world that can be confusing, complex and at times seemingly out of control, conspiracies offer us the illusion that we can understand reality without too much effort on our part.

A paranoid posture welcomes conspiracies not because people want to believe lies, but because they believe they’re already being fed them

During the pandemic you may have seen the film footage purporting to show empty hospitals. Anti-vax groups spread these videos across social media to illustrate their belief that the Covid-19 virus is a hoax: we’re being told there are lots of sick people, so why are hospitals eerily quiet? Although officials discredited the video, which simply showed calm outpatient areas during the peak of the crisis, the footage gained traction and was viewed thousands of times. Those who used it as ‘evidence’ were also keen to share other unorthodox ideas such as the great reset theory, which argued that a group of world leaders were using the pandemic to take control of the world’s economy.

You don’t need to go online to find examples of misinformation and conspiracy. On a recent walk, I saw a sticker that read: Vax ID Macht Frei, which is German for ‘The vaccine ID makes you free’. The text font mirrored the style of writing on the gates of the Nazi concentration camp at Auschwitz, which read, Arbeit Macht Frei or ‘Work makes you free’. At the bottom of the sticker was the name of an anti-vaccination group that was, unsurprisingly, named after a resistance group from the second world war. The sticker’s claim, that vaccine IDs (the now defunct government proposal to identify those who have been vaccinated) were a form of tyranny, appeared more plausible set against the backdrop of historical Nazi fascism. It might be a crass and grossly insensitive comparison, but for some it’s powerful propaganda: a lie based on false association that appeals to our emotions rather than our intellect. Putin used a similar technique to justify invasion when he claimed Russia would ‘denazify’ Ukraine.

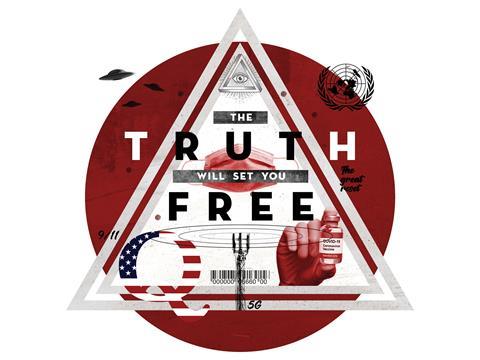

Christians in the US, in particular, have been linked to conspiracy theories, with real-world consequences. In two surveys from the Public Religion Research Institute, white evangelicals were found to be one of the most likely religious demographics in America to buy into one or more of the claims of the political conspiracy theory QAnon. The theory has been found to have shaped the motivations of Americans involved in the storming of Capitol Hill, which resulted in the deaths of at least two people.

QAnon started with cryptic posts on an online message board, but it soon went mainstream. The conspiracy theory alleges – among other claims – that a vast Democrat pedophile ring operates out of a pizza parlour in Washington DC. In the ‘canon’ of QAnon, Donald Trump is the leader of a movement resisting this hidden evil and there will be an apocalyptic moment (referred to as a ‘storm’) that will sweep away morally corrupt elites. It’s worth noting that white American evangelicals are not only more likely to believe elements of QAnon, they are also one of the least vaccinated religious populations in the US.

3 pandemic conspiracy theories

1. Big Pharma

The claim: Large pharmaceutical companies are suppressing natural remedies for Covid-19 and touting vaccines they know to be ineffective in order to increase their profits.

The truth: There are legitimate criticisms about the relationship of contracts and research funds to pharmaceutical companies, for example: the Opioid crisis in America. However, the notion that Big Pharma operates as a united evil entity with widespread impunity is not grounded in reality.

2. Lab Leak Theory

The claim: The Covid-19 virus was artificially developed in a Wuhan lab in China, and leaked (perhaps intentionally) to disrupt the global order.

The truth: Two recent studies cited by The New York Times in March of 2022 concluded the virus originated in the Wuhan Market. While it is of course plausible the virus emerged from a lab, the idea it was produced and/or released by nefarious agents and forces is conspiratorial and based on suspicion, not fact.

3. 5G

The claim: New 5G cellular network towers were causing people to get ill.

The truth: No links have been proven. Concerns about the new cellular technology pre-dated Covid-19. As the pandemic swelled, activists stoked conspiratorial suspicions and linked the pandemic to the technology as a way to leverage their activism with governments.

WHY DO CHRISTIANS BELIEVE CONSPIRACIES?

Pervasive distrust makes conspiracies plausible. When the government lies or the media misreports, distrust can fuel paranoia. For example, in the UK during ‘partygate’, when Prime Minister Boris Johnson lied repeatedly about social events that took place in government during the pandemic, trust in government plummeted. When people cannot trust their leaders, they turn to other sources of information. Now we have ‘alternative facts’ to counter ‘official narratives’.

Scandals in the media in recent times, such as phone hacking (and the denials of wrongdoing that came from certain newspapers), as well as innocent mistakes made by reporters may also be fuelling people’s changing perceptions of journalism as a force for good. This can lead to a mass exodus from traditionally trusted sources of information, such as the BBC and other mainstream outlets. This paranoid posture encourages conspiracies not because people want to believe lies, but because they believe they’re already being fed them.

Confirmation bias also makes us susceptible to conspiracy theories and, in this respect, Christians are no different from non-Christians: we interpret our world downstream based on what we believe upstream. For example, if you believe the earth is flat, you’re more likely to engage and share information that confirms this belief. This process is aided by algorithms online that serve you more of the content you usually click on and share. Because the world is fast-moving and we’re all prone to confirmation bias, information that doesn’t fit our worldview is swiftly dismissed rather than interrogated and weighed. “That isn’t real, it’s photoshopped,” is an easy response to an image that challenges our understanding of our world and our place within it. Heading upstream to question our foundational beliefs can be a long and painful process, one that many would prefer to avoid. And so lies beget lies.

Christianity is more scandalous than any conspiracy

Finally, Christians may wrongly assume our faith acts as a key to omniscient knowledge. The reasoning goes: because we know the truth, we must know all truth. Just because scripture presents an alternative understanding of ultimate matters – of human sin, death and salvation in Jesus – it doesn’t follow that anything claiming to be an ‘alternative’ take is true. Alternative and conspiratorial explanations of politics, pandemics or vaccines are not automatically more plausible.

In the New Testament, the apostle John reminded early Christians that “the whole world is under the control of the evil one” (1 John 5:19). With one eye on the Bible and the other on our world, conspiracy theories about hidden evil might seem attractive. After all, wasn’t there a hidden plot in Esther? Didn’t Daniel fall prey to a conspiracy against him? But we must ask ourselves another question: what did God intend when he gave scripture to the Church? Unlike conspiracies, scripture doesn’t entertain our quest for control or provide answers to our predictions and suspicions; in fact, it’s full of mystery. Perhaps John wrote Revelation not as a secret code for the next world order, but to help us imagine living true to the coming kingdom in any world order.

LOVE THY ANTI-VAX NEIGHBOUR

In 1943, Dietrich Bonhoeffer was reflecting on how German Christians embraced Hitler. He concluded that “stupidity is a more dangerous enemy of the good than malice… Against stupidity we are defenseless.” He was making the point that some Christians had exercised extremely poor judgement when deciding where their allegiance lay. But despite Bonhoeffer’s assessment of the situation, he checked himself: “Nothing we despise in other men is inherently absent from ourselves.”

It is easy to shame strangers – and even friends – who share conspiracies, but I read that quote from Bonhoeffer as an invitation to embrace a different approach. We can make a stand for what is right in ways that do not belittle others – and which might actually help to change their minds. Contempt only serves to coerce people into ‘correct beliefs’ through shame.

One way we can live in love with our anti-vax neighbours (or those that buy into any other conspiracy theory) is by learning the humility to more regularly say: “I don’t know.” Conspiracies offer a sense of superiority, of being ‘in the know’. We disrupt that misplaced confidence by embracing the posture that confesses our limitations. No one is completely correct in the beliefs they hold, theologically, politically or otherwise.

Neither do we enjoy finding out we’ve believed a lie; we all appreciate being given the dignity to change our minds without shame.

We can also learn the art of persuasion. Minds are changed over time. Arguments are not persuasive but combative. Picture truth not as one massive boulder we roll down a hill at someone in an argument, but instead, as one of those annoying pebbles that get stuck in your shoe. Eventually, you have to stop walking, take off the shoe and deal with the pebble. Persuasion is the act of placing pebbles of truth in people’s shoes. They can come as questions, honest conversation or empathy that seeks to understand someone else’s perspective.

WHEN CONSPIRACIES COME TO CHURCH

Within this landscape, it is likely that conspiratorial outlooks are held by some in our churches. And while I may be advocating for a compassionate approach, when it comes to discussing conspiracy theories with Christians, I would err on the side of caution. It is imperative that non-believers who come to our churches to explore Christianity do not leave thinking they must embrace these theories to enter the kingdom of God. It may not be the task of those in the pulpit to denounce political conspiracies week in and week out, but the Church does have a role to play in forming Christians who are bearers of truth. Paranoia is not the lens through which Christians should view the world, or as Philip Yancey once said: faith is “paranoia in reverse”.

Ironically, Christianity is more scandalous than any conspiracy. It takes an act of God in us to confess that all reality hinges on a Jewish peasant hanging on a criminal’s cross in a backwater province of the Roman Empire. The Church confesses that this man is the creator God incarnate, the God of Israel, resurrected, reigning over and reconciling the entire cosmos to himself. But while the grace of God brings us to recognise that Jesus is Lord, it doesn’t provide transcendent knowledge about what’s going on in Whitehall or the White House; we have brains and experts for that. Conspiracies may confirm our suspicions and allow us to feel we’re in control, but they corrupt our Christian witness. So rather than reducing the complexities and chaos of the world to a few neat theories, why not embrace our faith and “the peace of God, which transcends all understanding” (Philippians 4:7). In this process we must not sever our connections with people who believe conspiracies, because when Jesus said, “love your enemies” and “love your neighbour” (Matthew 5:43-44) he kept a door open for change; one we must not shut through contempt or cynicism.