The world’s longest-running research project is (still) trying to find out what makes humans happy. Martin Saunders distills years of study, ancient biblical wisdom, endless self-help books and that Ken Dodd song to finally give you the answer…

In 1964, the British comedian Ken Dodd covered a little-known country song, and it reached a modest number 31 in the UK singles chart. Sometimes, however, the impact of a song grows over time, and this track seeped much more broadly into the public consciousness over the next 60 years. You might well recognise the chorus: “Happiness, happiness / The greatest gift that I possess / I thank the Lord that I’ve been blessed / With more than my share of happiness.”

It’s a simple song — perhaps not even a particularly good one. Yet somehow it transcended its humble beginnings to the point that most people over 30 could at least hum along. Why? Because deep down, perhaps it nudges at the most basic aspiration we all hold for our lives. Above all, we just want to be happy.

The question is: what actually is happiness? And beyond that, how can we truly achieve it?

The answers might not be as simple as we imagine.

A cultural obsession

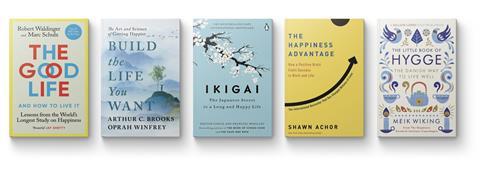

In the current sea of self-help and personal development ideas, the apparently simple concept of happiness looms large. There’s a plethora of popular books on the subject (see box).

The truth, however, is that despite the plethora of angles (neurological, spiritual, cultural and even mathematical aspects) of happiness to explore, in most cases they end up in much the same place. There is consensus that most of the things we chase after do not make us happy, and that true happiness is about more than a feeling. There’s also a fairly universally agreed group of practices and pursuits which get us to that sought-after place beyond simple pleasure. In many cases, the evidence for these ideas draws from a limited range of sources – including the Bible.

At Harvard University, the Study of Adult Development (also known as the Harvard Happiness Study) has been running since 1938. It is the world’s longest-running research project into what constitutes a happy life, and one of the most in-depth longitudinal studies ever conducted. Its findings are co-opted into the pages of many books, but most significantly reported in The Good Life, written in 2023 by Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz (Rider), the current directors of the study. Despite the depth of the research, the liberally quoted findings are remarkably simple. In the end, the key to happiness is found in the quality of your relationships.

Yet the breadth of discussion on the topic suggests that such conclusions are unwelcome. It’s as if the world, searching for happiness, makes this discovery and says: “There must be more than that.”

Why aren’t we happy?

So why is this simple concept so enticing and elusive? The answer to the first part of that question is easy: generally speaking, people are not happy. Or rather, there is a sense that the things we do to make ourselves happy do not quite hit the spot. Quotes abound telling us that money can’t buy it, yet that doesn’t stop us spending billions in attempts to prove otherwise.

The sociologist Jonathan Haidt, author of The Happiness Hypothesis (Random House Business), describes two conflicting psychological phenomena which help to explain why. All of us, he says, are motivated by a kind of “Progress Principle”, which sees us locked in a constant striving to improve our circumstances, whatever the starting point. Škoda drivers aspire to one day own a Volkswagen; Porsche owners aim up at a Ferrari. We believe that this will make us happy and, in a sense, it does. Until the second of Haidt’s principles kicks in. The “Adaptation Principle” says that after a period of time – probably no longer than a year and in many cases much less – we will take our new circumstances for granted and derive no more pleasure from them. The only way back to happiness is to aim for more again…and the new Ferrari owner orders a brochure from Bugatti.

These phenomena don’t only apply to material possessions, but also to career ambitions – and a range of other pursuits in which we might anchor a quest for happiness. They are the practical explanation behind quotes like Jim Carrey’s famous line: “I think everybody should get rich and famous and do everything they ever dreamed of so they can see that it’s not the answer.” We enjoy progress, but we get used to the improvement, sending us endlessly and fruitlessly chasing more. How much of the world’s current malaise can be at least partly explained by that chase?

The little book(s) of happiness

The happiness self-help sub-genre has exploded in the last two decades, with scores of bestselling books appearing with their own spin on the subject. Here are some of the most significant.

The Good Life by Robert Waldinger & Marc Schulz (Rider) - Harvard Happiness Study researchers find the surprisingly simple key to happiness is…strong relationships.

Build the Life You Want by Arthur C Brooks & Oprah Winfrey (Rider) - Famous TV presenter joins forces with recent HTB leadership conference speaker to list cutting-edge strategies for emotional mastery and deeper happiness.

Ikigai by Héctor García & Francesc Miralles (Hutchinson) - Explores the Japanese concept of ‘a reason for being’, and how finding a sense of meaning and purpose can lead to lasting, type-two happiness.

The Happiness Advantage by Shawn Achor (Virgin Books) - Based on his popular TED talk, Harvard-trained researcher Achor suggests that happiness fuels success, rather than the other way around.

The Little Book of Hygge by Meik Wiking (Penguin Life) - Many Danes believe that happiness comes through togetherness, coziness and comfort; this book seeks to take that concept to an international audience.

Two kinds of happy

The extensive literature on happiness and how to achieve it all pivots on one central idea: that there are different kinds of happy. The base level – gratification or pleasure – is the version we chase every day. This is the kind of sensory, dopamine-releasing stuff that might define whether we had a good day: a great meal, an enjoyable night out at the theatre…[insert your own favourite pastime here]. Ultimately, though, the ‘happiness’ we experience from these activities will inevitably fade. The dopamine effect wears off and we reset to our baseline mood. In a nutshell, this is why the things that we buy or do can’t give us a lasting sense of happiness.

Thankfully, there’s another version which can bring lasting fulfilment. Beyond the short-term, dopamine-chasing quest for ‘hits’ of happiness there’s a much longer-term sense, sometimes called contentment, or even meaning. This is a kind of sustained happiness, a feeling that our entire lives are going well, count for something and aren’t being wasted. It isn’t achieved by a single definitive action or experience – even one like marrying the right person or having a child – but rather it’s the result of a network of life decisions which integrate to form a ‘good life’.

The existence of so many books that try to formulise this second kind of happiness is testament to how elusive it is. In fact, given that the overwhelming majority of these publications have appeared in the 21st century, it would seem that this challenge is only becoming more pronounced. Mental health statistics suggest that it’s actually worse than that: many of us are struggling with a profound sense of unhappiness, fear, loneliness, anxiety – even depression. Maybe in the simpler 1960s, Ken Dodd found the great gift of happiness much easier to possess than we do. By contrast, we live in a time where instant gratifications are a far larger part of the human experience. We’ve never had more options for fun or more liberty to indulge ourselves in whatever way our particular moral code allows. And yet, all that fleeting pleasure reveals a wider sense of emptiness and longing underneath.

The original happiness Bible

Anyone looking to Jesus or the Bible as a source of happiness must understand the distinction between gratification and contentment, or they will be deeply disappointed. Although there are branches of the Church that seem to promote a kind of self-help gospel, which promises the answer to all your earthly problems and a life of unbridled prosperity and pleasure, you won’t find the basis for it in scripture.

The Bible is a million times more powerful than any self-help book

For version one of happiness – the simple experience of regular everyday pleasures – one has to resort to proof texts that are ripped out of context – Malachi 3:10’s promise that bringing “the whole tithe into the storehouse” will see God “throw open the floodgates of heaven and pour out so much blessing that there will not be room enough to store it”, and Luke 6:38’s: “Give, and it will be given to you. A good measure, pressed down, shaken together and running over, will be poured into your lap.” These favourites of the prosperity movement are generally used as a lever in a Christian pyramid scheme, where paying in some of your earthy resources will unleash all manner of life-enhancing blessing in return.

Yet even if that equation does work out, it is not guaranteed to bring lasting happiness and is by no means the Bible’s most important offer in this area. Rather, the gospel offers something much more significant: the second and harder-to-achieve idea of happiness – a contented and meaningful life. Jesus speaks of it when he encourages those who are “weary and burdened” to come to him for true rest in Matthew 11:28, and when he promises “life..to the full” in John 10:10. Paul writes in Philippians 4:11 that he has “learned to be content whatever the circumstances”, having had experience of both poverty and privilege. The secret, he says in verse 13, is to do everything “through him who gives me strength”.

So, what does that look like in practice? Beyond the obvious signpost to Jesus, what’s the Christian answer to this culture’s ravenous search for lasting happiness?

Happiness, the Jesus way

Disappointingly, Jesus never invites his followers to kick back and enjoy themselves. He does place a big emphasis on pleasant mealtimes, but these are always in service of his greater focus: human relationships. In fact, this is where Jesus and the Harvard Happiness Study become completely aligned; Jesus models close relationships with his family and friends and repeatedly stresses the need to connect with and care for neighbours. Individually speaking, this does prove a source of contentment and meaning for many Christians, especially when they follow Jesus’ lead directly and enter into the sufferings of others.

Where this can start to become really powerful, at least in theory, is in the context of a local church. A church can become a source of all kinds of contentment-inducing joys: good friendships, a sense of belonging; shared purpose and the pursuit of practical activities which make a local community better. During collective worship, we shed our sense of shallow individualism and enter into a communal act of meaning-making. We experience the Holy Spirit and become aware of the vastness of God; we sense awe and wonder at his unfathomable love and our inclusion in his global, history-spanning story.

Quotes abound telling us money can’t buy happiness, yet that doesn’t stop us spending billions in attempts to prove otherwise

And in the Bible, we have access to a self-help book that is a million times more powerful than the rest. A regular habit of reading and praying through scripture exposes us to a constant stream of wisdom, while slowly building a sense of God’s character and overarching mission. This imbibes our lives with meaning and hope. Read this book, and find true happiness.

A range of other spiritual practices and disciplines, tried and tested over the centuries by Christians everywhere, further deepen our connection with a much greater power and story beyond ourselves. Prayer, fasting, silence, meditation, service; all of these dopamine-suppressing activities can counterintuitively increase our sense of contentment. In short, we have the very thing the world is searching for.

Searching in all the wrong places

Despite encouraging signs that many in our culture are now starting to explore spirituality – and Jesus – as the answer to their unfulfilled longings (see, for example, pretty much every other page in this magazine), there are plenty of other contenders.

Here are some of the most common places that society looks for joy – only to find them empty:

1. Achievement and success

From exam results to work promotions, we can often tie our worth to our performance. But when the applause fades, so does the sense of happiness. Ecclesiastes 1:14 reminds us that even great accomplishments can be “meaningless, a chasing after the wind”.

2. Material comfort

The progress principle promises us that the next gadget, car or holiday will finally make us happy. Often, though, the more we accumulate, the more discontented we actually feel. Jesus speaks into this in Luke 12:15 when he reminds us: “Life does not consist in an abundance of possessions.”

3. Social media validation

Thanks to the accompanying dopamine hit, likes, shares and follows can offer a fleeting sense of reward and self-worth. However, a culture of curated images and constant comparison often leave us lonelier than before. True joy isn’t found in digital approval but in knowing we are fully known and loved by God, precious and honoured in his sight (see Isaiah 43:4).

4. Relationships and romance

Though relationships are a gift from God, they were never meant to be our ultimate source of fulfilment. Even the best friendship or marriage can’t bear the weight of being our ‘everything’; humans will always ultimately fall short of what Jesus can offer in meeting our deepest needs.

5. Escapism and entertainment

Streaming, scrolling and bingeing may provide momentary distraction, but they never leave us truly satisfied. Contentment can’t be found in avoiding reality, but in rolling up our sleeves and entering into it with Jesus who promises never to leave or forsake us.

The greatest gift that we possess

That old Ken Dodd song isn’t quite as vacuous as it first appears. The first verse acknowledges: “I’ve got no silver and I’ve got no gold, but I’ve got happiness in my soul”; a recognition that money clearly isn’t the catalyst of joy. Instead, Dodd sings that: “Happiness to me is an ocean tide / A sunset fading on a mountain side / A big old heaven full of stars above / When I’m in the arms of the one I love.” Awe and wonder, deep human relationships. The song might not be pointing to Jesus, but it’s certainly in agreement with him.

In Mere Christianity (Collins), a slightly more intellectual figure, CS Lewis, writes: “If I find in myself desires which nothing in this world can satisfy, the only logical explanation is that I was made for another world.” That is our resonant response to culture’s wholesale, fruitless search for happiness. That other world reaches into ours through its king, who tells his followers in John 15:11 that their “joy may be complete” if they remain in him. And in the very next verse, he explains how they can both practise his way and experience true contentment: “Love each other as I have loved you.”

The science, self-help books and scripture all agree: true happiness is only found when we love one another.

No comments yet