David Instone-Brewer explores what scripture teaches about women in wartime

One of the fiercest warrior-leaders in history, who stopped a huge Roman army invading her land and lost an eye doing so, was Amanirenas, the Kandake (ie queen) of the Ethiopians.

There’s a queen of the Ethiopians mentioned in the New Testament too. Acts 8:27 tells us that Philip was instrumental in converting an “Ethiopian eunuch, an important official in charge of all the treasury of the Kandake.” This verse is referencing Amanirenas’ daughter, Amanishakheto. She was certainly rich – some of her crown jewels are today on display in German museums.

Recently, archaeologists have made discoveries that suggest ancient warrior women weren’t as rare as we’d thought. One of the occupants of the royal tombs containing the family of Alexander the Great has recently been confirmed to be his half sister-in-law, who was a warrior. Previously, the armour it contained was thought to belong to Alexander himself.

In the UK, too, the presence of armour or weapons were previously assumed to mark male graves. But it turns out that three per cent of the warrior tombs that are reassessed using DNA belong to women. This confirms historic accounts of a few women like Boudicca, who led an army in an uprising against the first Roman invaders.

Women in the Bible

Historically, Judaism lacked female warriors. The Old Testament does tell us about Jael, who killed an enemy leader and Deborah, a judge who also headed up an army (Judges 4). However, Jael lured her victim into a tent, and Deborah encouraged her army but a man led them into battle, so they weren’t really warriors in the traditional sense.

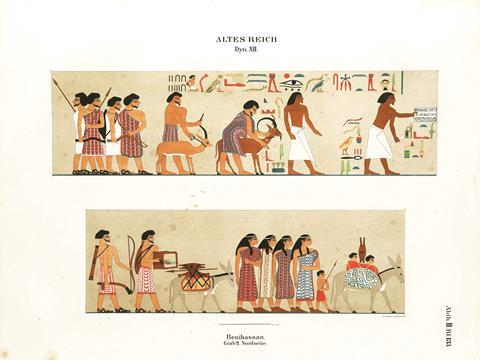

Perhaps female warriors were discouraged in Judaism by the law which forbade women from dressing like men, and men dressing like women (Deuteronomy 22:5). Men and women in ancient Israel had outwardly identical clothing, as we see in a colour picture of a typical Canaanite family preserved in a tomb from the time of Jacob (see here). The women are robed from their shoulders to their calves, with their arms and one shoulder bare – and the men are dressed identically, except for having beards.

However, the painting also depicts some men who are dressed differently: bare-chested, carrying things and working. Interestingly, the multicoloured clothing in the picture is similar to the coat we imagine Joseph had. The Hebrew actually implies that Joseph’s robe had sleeves reaching his hands (Genesis 37:3). Long sleeves impeded practical work, so this gift implied a life of leisure, which would certainly inspire jealousy. Those with the shortest garments did the hardest work.

The clothing depicted in the ancient mural coheres with the law against cross-dressing in Deuteronomy 22:5, because although women did wear similar clothes as men at leisure, they didn’t go bare-chested like labourers. The Hebrew confirms this distinction because it doesn’t forbid a woman (Hebrew ishah) dressing like a “man” (ish); it forbids her dressing like a “strong man” (geber) – which normally denotes a warrior or other muscular worker. And, of course, in Jewish society it was indecent for a woman to be bare-chested.

Spared

This law represents a remarkable concession for women in ancient Israelite society because it prevented them being warriors. The nation was on a near-permanent war-footing – after the Exodus, they lived among enemies for centuries. In the wilderness of Sinai, they were immediately attacked by Amalekites. And when they entered Canaan, they certainly weren’t welcomed by the city-states dotted around the area. This meant they had to be prepared for battle at all times. Every male over 20 was expected to fight unless he had religious exemption (Numbers 1:1-3,47-50). Only women, children and teenagers were excluded.

Women were spared not through sentiment, but because of cold logic: they were too precious to lose in battle. It was they who gave birth to children and kept everything in society working. We glimpse this in the aspirational role model presented in Proverbs 31: she runs a business, trading in the market and dockside, and earns enough to let her husband be an unpaid magistrate (vv10-28). Protection of women also made economic sense in an agricultural society where the number of your children represented your farm’s profitability and your nation’s strength.

A few years ago, someone told a friend of mine that she shouldn’t wear trousers while preaching. Were they correct? The fact that Deuteronomy forbids women dressing like a “strong man” rather than like an ordinary “man” suggests that its purpose was to ensure women didn’t do hard labour or, more importantly, military service. It also prevented men avoiding military call-up by cutting their beard to look like women.

The principle behind this law is that we do what our God-given skills have made us best at. Israel, like many nations, now allows women in the military. We know that the female wall-watchers warned their commanders about Hamas’ plans long before the dreadful attacks on 7 October.

God wants us all to fulfil our role in society to the best of our gifts, skills and ability – as carers, teachers, business leaders and Christian workers. The terrible sadness today is that women are needed in the military in countries like Israel and Ukraine, and are sometimes even fighting on the frontline – and no one wants that.

No comments yet