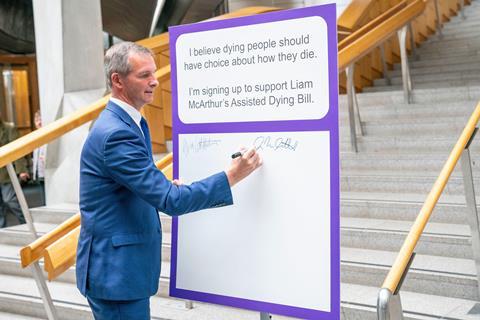

This week a new bill to legalise assisted dying won the right to be considered in Scotland’s parliament, but legislators must keep the door firmly closed, says Jamie Gillies. The lives of the most vulnerable depend on it

On Monday, the politician behind plans to legalise assisted suicide in Scotland confirmed that his member’s bill has achieved sufficient support to progress in the Scottish Parliament. The Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults (Scotland) Bill is now set to be considered by Holyrood’s Health Committee.

It’s the third time Scottish politicians have looked at a proposal along these lines since devolution in 1999. Previous attempts to pass new legislation failed, but this time the outcome could be different, given the arrival of ‘assisted dying’ in other western nations.

The success of this bill so far is extremely saddening to many in Scotland – in the Christian community and more widely. Disabled people are among the staunchest opponents of euthanasia, alongside palliative doctors and professionals working in suicide prevention.

It was particularly sad to hear news of the legislation on Monday, which was World Mental Health Day. Dr Miro Griffiths, an expert on disability and a personal friend, noted the irony of this: “Promoting the mental wellness and flourishing of human beings means holding to a consistent standard regarding the value of human life”, he said. In stark contrast, assisted suicide undermines human dignity by creating a “pernicious exception where some people, coping with some circumstances, get no help”. He added: “In nations where assisted suicide is legal, we have seen an undeniable lapse in the value ascribed to human beings”. Disabled people “are not given the respect, protection, and affirmation they deserve”.

Even children now have the right to end their lives prematurely in some countries

One such nation is Canada, where reports of abuse and discrimination under a ‘Medical Aid in Dying’ (MAiD) law are being issued at an alarming rate. Only a few days ago, a doctors’ group in Quebec was criticised for suggesting that babies born with a serious health condition should be eligible for euthanasia. There’s a word for this: infanticide.

Canada introduced assisted suicide for people with a terminal illness in 2016. At the time, campaigners said availability would remain ring-fenced for those already dying. There would be no ‘slippery slope’, in other words. Less than a decade on, Canada’s law allows assisted suicide and euthanasia for disabled adults. From 2023, adults with mental illness will also have access. Dark predictions have come true.

In European nations something similar is happening. In Belgium, where roughly five people a day die by assisted suicide, the depressed can request euthanasia and terminally ill children now have the right to end their lives prematurely. In The Netherlands, campaigners are now vying for those over 75 years old to get access to euthanasia if they believe they have “completed life”.

State-facilitated death

Is all this really indicative of a civilised society? Or does it indicate a disregard for human life? The dangers of allowing state-facilitated death are real, and alarming. Scottish politicians need only look to the countries mentioned above to see that abuses occur, and laws spiral out of control. When a society opens the door to assisted suicide, it throws open a sinister Pandora’s Box. Hitherto unseen injustices will occur, which impact the oppressed and vulnerable the most.

In some ways, Christians shouldn’t be surprised by any of this. In a society that has long since forgotten God, is it any wonder that the Imago Dei – the image of God – found in humanity is disregarded too. We believe that the taking of human life and facilitating of a person’s suicide are morally wrong. A society that affirms such activities undermines human dignity and compounds human suffering. Conversely, a society that affirms the preciousness of every person, regardless of their circumstances or personal characteristics, is blessed.

A right understanding of human life, grounded in Christian values, has given rise to so much that is good in our society: the welfare state; the National Health Service; the hospice movement; social care; suicide prevention.

We must extend the hope of the Gospel to people who feel life has no hope at all

As followers of Christ, we must herald a positive, alternative path for our society to follow that doesn’t involve prescribing poison to people who are suffering. We must seek investment in mental health services, world-leading palliative care and better conversations about how the end-of-life can be improved. And above all, we must extend the hope of the Gospel to people who feel their life has no hope at all.

In months to come, Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) will grapple with these issues. Some very deeply indeed. I would ask them to think carefully about one thing in particular: Regardless of where they stand on the morality of ‘assisted dying’ itself, are they prepared to risk the slippery slope of abuses that have beset other countries? Under a Scottish Assisted Dying Act would the most vulnerable be better or worse off?

With strong evidence of safeguards failing or being weakened and laws being extended in other nations, how can they be so sure these outcomes won’t occur in Scotland? The real questions are: how long before they do, and how bad will they be?

The only real guarantee against a future that looks like Canada’s, Belgium’s, or Holland’s, is to keep the door to assisted suicide firmly closed.

But I’d also ask MSPs if they think a dose of lethal drugs is the best Scotland can offer to people who have been hit with a terminal diagnosis? Is this Nihilistic approach really the positive, compassion-led response that Scottish citizens deserve? It’s certainly not my vision for our beautiful country, and I pray it won’t be the vision of Scotland’s parliament either.

Stand with Premier against the latest legislation. To sign the petition and email your MP visit premier.org.uk/forlife