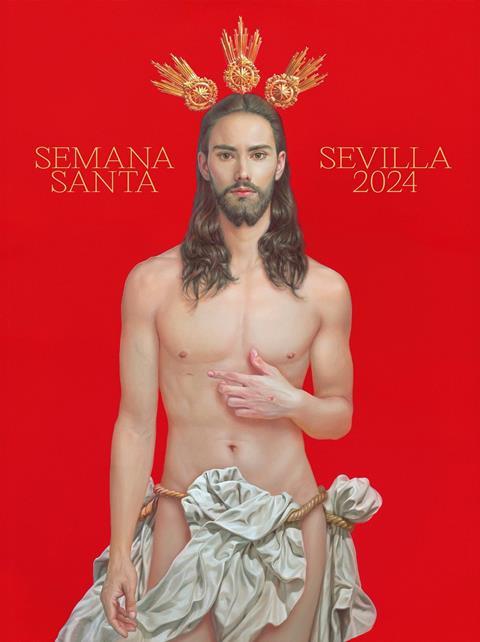

Can a ‘sexy’ poster of Christ serve as a good invitation to church? Or does the furore that has surrounded it say more about our relationship with our body than the artist’s actual intention?

A storm has broken out across the Spanish city of Seville over a new painting of the risen Jesus commissioned by the Roman Catholic diocese.

Designed as a poster to invite people to church over Easter, the image has angered conservative Christians and the political right, who claim it is homoerotic and inappropriate. Thousands of people have signed a petition calling for it to be withdrawn.

Living in an image-drenched age, and one that values bodily perfection, it is unsurprising that this new painting is attracting attention. The figure of Jesus, smooth chested and with a touch of muscle definition, is the on-trend look many men aspire to. That the painting has been described as “effeminate” underlines that this is metrosexual manmade flesh.

To never put a stumbling block in the way of another is surely good advice

The artist, Salustiano García, defended his work, claiming that: “Those who see something dirty in the painting are only projecting their own internal dirt on to the image.” His comments are reminiscent of Titus 1:15: “To the pure all things are pure.”

García added that his aim was to focus on the resurrection as the most luminous aspect of Easter in his photo-realistic portrait.

Illustrated history

We know virtually nothing about what Jesus actually looked like. Our best guesses are drawn from a generalised appearance of Middle Eastern Jewish men of the time. In fact, the Bible rarely describes people’s appearances, and from this, perhaps we can conclude that it isn’t something the authors – or God – consider to be of high importance.

The legitimacy of creating an artistic representation of Jesus was hotly debated in the first centuries of the Church. It was ultimately decided that God, having chosen to take on flesh, could be depicted through Jesus and that this might be helpful in communicating the gospel in an age where few people could read.

By the Renaissance it was normal to see biblical scenes, including the life and the crucifixion of Jesus, in paintings and stained glass across Europe. The bystanders wore clothes of the fashion at the time and the Tuscan hills in the background emphasised that Jesus is timelessly relevant.

Body issues

Jesus, although almost certainly naked on the cross, is traditionally painted with a loincloth, sparing him the humiliation that the Romans subjected him to. So, too, in this new painting, but the cloth is held loosely by a rope and looks like it might fall to the ground at any moment. Is this deliberate titillation by the artist, or does this reveal something about our own disordered appetites, damaged by the world we live in, that we even ask such a question?

In the early 1980s, at the start of his ministry, Pope John Paul II spent several years giving a weekly address that would eventually be gathered into a book, Theology of the Body (Alba House). The breadth of its scope is matched only by the precision with which it targets the gospel in our times, more than 40 years after it was written.

However pure the intentions, art can never be detached from the way an audience receives it

In the work, John Paul II argues that the problem with our relationship with nakedness is not that we think more of the body than we should. Rather, it is the opposite; we do not think nearly highly enough of it. Pornography is a problem not because it reveals too much but because it reveals too little. He argued that paintings which depict nakedness can be beautiful, and that even a photograph can reveal something of great value but, he cautioned, the more realistic the portrayal, the more responsibility rests with the artist to not lead the viewer into moral difficulty.

Intentions and impact

We live in such a broken world. Our relationship with naked imagery and our distorted view of what constitutes a beautiful body makes us all vulnerable in the face of ambiguous pictures that stimulate unhelpful emotions and responses.

Perhaps we can apply the words of Paul in Romans 14:13 or 1 Corinthians 8:9, which were written in the context of Jewish food laws but also have a wider application. To never put a stumbling block or hindrance in the way of another is surely good advice.

Ultimately, I side with those calling for the poster to be withdrawn. However pure the intentions, art can never be detached from the way an audience receives it. García might be right that our reaction reveals more about our brokenness than his intention, but that doesn’t mean he is resolved of all responsibility, or that it works as an Easter invitation to church.

We cannot know if the artist set out to be controversial. Perhaps the diocese was naïve to commission and publish the art, given its likely reception and potential to offend. But, if the purpose of advertising is to be noticed, we might have to reluctantly agree that they’ve achieved their goal.

No comments yet